Donald Trump has repeatedly declared himself the “law and order” candidate, wearing this mantle proudly. At last week’s Republican National Convention, the array of speakers trumpeted this slogan again and again as the dominant chord of Trump’s otherwise ill-defined policy platform.

“Law and order” isn’t just the definitive slogan on Trump’s candidacy; it’s deployed as a distinguishing one, as Trump at the same time differentiates Joe Biden as one who will bring anarchy, chaos, and lawlessness to American cities, suburbs, and every other corner, nook, and cranny of the land.

Biden’s campaign has fought back to some extent, asserting that he does not support defunding the police and reminding Americans of the salient, if obvious, fact that the violence and disorder we have all witnessed over the past summer have been occurring under Trump’s leadership, not his.

But this response is still insufficient, at least from a rhetorical standpoint, because it does not fully encompass or draw into relief the connection between the anti-racist agenda that is an overt element of the Biden-Harris campaign and its related and more implicit agenda of equal justice for all, of equal protection under the law for all, which is a more genuine version of law and order.

Biden and Harris need to proudly and loudly assert their promotion of law and order in just these terms—equal justice and protection—and differentiate it from Trump’s version of law and order characterized by repression and violence and a complete disregard for due process.

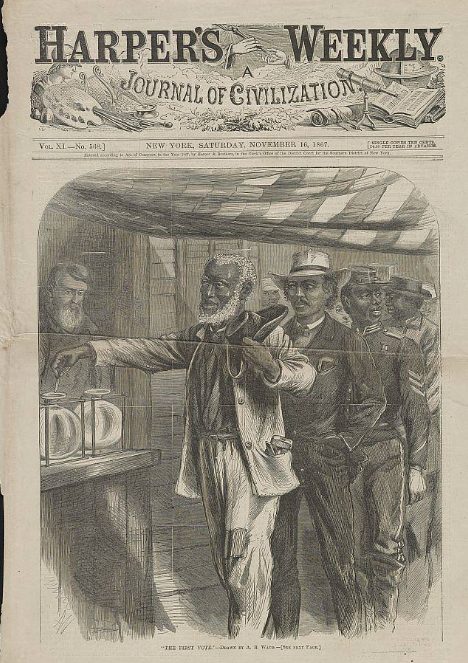

Biden and Harris are not opposed to law and order; they are opposed to repression and inequality under the law. What they want is a version of law and order that embodies the actual principles and ideals of our nation—liberty and justice for all—rather than the deeply embedded and often unspoken principles of racism and inequality that have informed institutional and cultural life in America since its inception.

L.A. Clippers coach Doc Rivers pulled back the curtain on Trump’s racist and repressive conception of order, which is bereft of any connection to the rule of law, in his recent comments on the Republican National Convention, making clear that a genuine call for law and order is not only consistent with but necessary for achieving the goals of the Black Lives Matter movement:

“All you hear is Donald Trump and all of them talking about fear. We’re the ones getting killed. We’re the ones getting shot. We’re the ones that we’re denied to live in certain communities. We’ve been hung. We’ve been shot. And all you do is keep hearing about fear.”

Rivers articulates a basic desire to feel safe and unafraid in one’s world and daily life, to not have to worry about being shot or hung, and to not endure the lack of freedom that our de facto segregated society entails.

He wants the law to represent his life and all Black lives.

The hit television series Law and Order opens with what must be by now the culturally iconic introductory mantra: “In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: the police who investigate crimes and the district attorneys who prosecute the offenders.”

This opening is the expression of an ideal, not a reality. Currently these two arms of the criminal justice system are not representing people of color in the U.S., as Rivers makes clear.

Unfortunately, though, the language of “law and order” still seems to be largely Trump’s property, and Biden, the Democrats, and Black Lives Matter would do well to re-possess it and not simply cede it to Trump. To many voters, the phrase resonates, because who doesn’t want law and order? Language matters. Again, the language needs to be re-claimed and invested with a new content, a new meaning such that we do understand that the justice system should and must actually represent all people’s interests with equity and that we aspire to that reality.

Not seeking to reclaim this language is dangerous. Just take this reporting by Kevin Breuninger for CNBC in a piece he wrote on Jared Kushner’s response to the protests by NBA players:

“Trump has taken a hardline stance against violence that has come out of a massive wave of protests against police brutality and systemic racism in the wake of George Floyd’s death. He has called for the federal government to intervene in Kenosha to clamp down on the unrest but has not tweeted or commented publicly about Blake’s shooting.”

Trump, in fact, has not taken a “hardline stance against violence.” He has said nothing about the fact that Kyle Rittenhouse, the 17 year-old extremist who actually murdered people with an AR-15 at the Kenosha protests, was actually thanked by police for his presence and assistance at the protests.

Trump supports a white supremacist order empowered to take lives and repress others, particularly those of people of color.

This fact needs highlighting at every turn so that reporting such as Breuninger’s is countered by the likes of Kareem Abdul Jabbar, who recently wrote in The Guardian:

“In Pence’s speech, he told America: “Dave Patrick Underwood was an officer of the Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Protective Service, who was shot and killed during the riots in Oakland, California.” What he neglected to mention was that federal authorities say Underwood was killed by Steven Carrillo, an Air Force staff sergeant who was a member of a right-wing extremist group whose purpose is to start a race war.”

Jabbar makes clear that Trump has an interest in a white supremacist order, but no interest in the rule of law.

An anti-racist agenda is a law and order agenda, calling for an order reflective of laws that embody the nation’s stated ideals and ambitions of equal protection and justice under the law for all. It is a call for laws that embody the ideal of equality.

Let’s take this language back from Trump. Language matters, and it can help us represent how lives matter.

Tim Libretti is a professor of U.S. literature and culture at a state university in Chicago. A long-time progressive voice, he has published many academic and journalistic articles on culture, class, race, gender, and politics, for which he has received awards from the Working Class Studies Association, the International Labor Communications Association, the National Federation of Press Women, and the Illinois Woman’s Press Association.