Global Solidarity and Tactical Radicalism: The Black Power Movement

Evolution of Revolutionary Black Nationalism

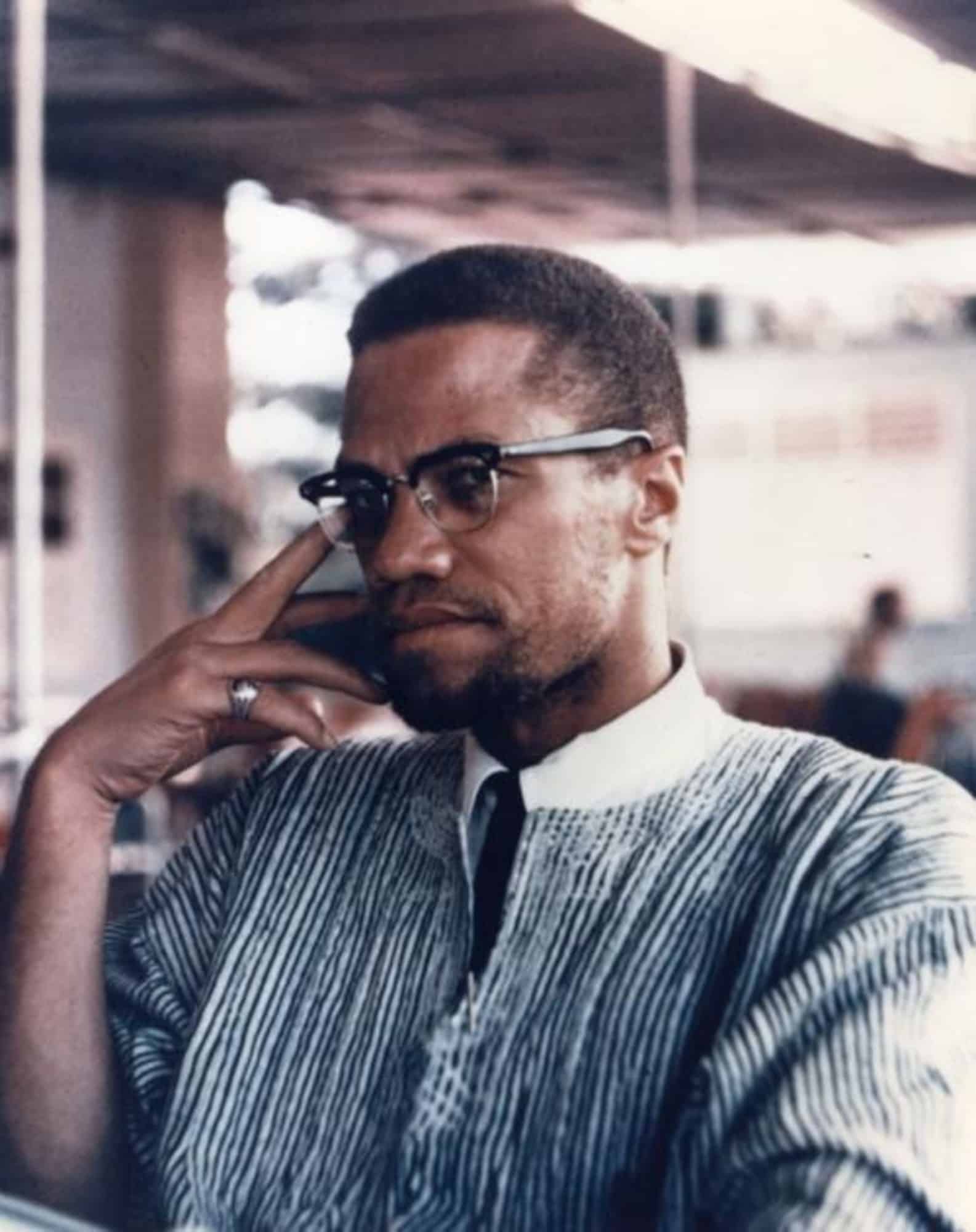

Revolutionary Black Nationalism evolved most directly out of the movements of the 1960s. It represented a fusion of the ideology of Malcolm X and young Black activists. Malcolm X, constantly traveling the country as the national spokesman of the Nation of Islam, was regularly exposed to emerging trends in the Black movement. His dynamic interaction with Black leaders, activists, and grassroots organizations across the country played a critical role in the evolution of his thinking. His ideology didn’t remain stagnant — it deepened through constant learning, reflection, and engagement with new ideas. In his later years, after leaving the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X had grown close to many of these young activists, some of whom had joined SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Many were also drawn to the example of Robert F. Williams, who organized a Black rifle club in Monroe County, North Carolina to defend the Black community and mass demonstrations against the Klan and racist violence.

These activist who looked up to Robert F. Williams and wanted to create conditions within the US for him to be able to return from exile formed the core of RAM, the Revolutionary Action Movment. They also studied the Chinese revolution and the theories of Mao Tse Tung. The leading theoretician of this current was Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford) the former field chairman of RAM and a close associate of Malcolm X in his later years. Stanford outlined his world view in a pamphlet publication entitled, Basic Tenets of Revolutionary Black Nationalism.

The Black Power Movement

As the movemnts of the 1960s started to converge, the Black Power movement emerged, capturing the imagination of young black activists, many of whom grew frustrated with turning the other cheek and non-violence in the face of police repression and white Southern attacks on the civil rights movement using fire hoses, dogs, and fire bombing. The Black Power current is the radical imagination made real. Drawing from anti-colonial movements, Pan-African solidarity, and revolutionary theory, it asked not just what America owed Black people — but what Black people owed each other, globally. Organizations like RAM, the Black Panther Party, and the Republic of New Africa fused political education with survival programs — free breakfasts, health clinics, and liberation schools that met immediate needs while building long-term consciousness.

This current was internationalist by design. It forged connections with Algeria, Cuba, Ghana, and the Caribbean, global Pan Africanism, situating Black struggle within a global fight against imperialism. Its young leaders — Stokely Carmichael, Max Stanford, H. Rapp Brown, Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Elridge Cleaver, Fred Hampton, Assata Shakur — challenged the boundaries of citizenship, loyalty, and liberation.

However, there was also an older generation of leaders whose lineage stretched back as far as the Garvey Movement and the anti-imperialist and pro self-determination eras of the mid-twentieth century. This old guard either guided or influenced these young radicals, im particular, RAM, and their emerging ideology. Among this older cadre of leaders was Queen Mother Moore, Abner Berry, James and Grace Boggs, Harold Cruse, and others. Revolutionary Black nationalism remains the most ideologically expansive current, insisting that Black freedom is inseparable from global justice.

Timeline: Revolutionary Black Nationalism (1959–1983)

| Year | Event | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Cuban Revolution inspires Black radicals | Global anti-imperialist model |

| 1961 | RAM formed at Central State University | Applies Maoism to U.S. conditions |

| 1963 | Malcolm X endorses RAM and mentors Max Stanford | RAM becomes only secular group Malcolm formally supported |

| 1964 | Malcolm X visits Africa and Middle East | Builds Pan-African alliances |

| 1966 | SNCC adopts “Black Power” slogan | Breaks from liberal integrationism |

| 1966 | Black Panther Party founded in New York by RAM activists | Symbolic use of Panther icon; no armed patrols |

| 1966 | Black Panther Party for Self-Defense founded in Oakland | Armed self-defense + community programs |

| 1968 | RAM dissolves under FBI COINTELPRO repression | Marks early federal targeting of Black radical groups |

| 1968 | Republic of New Afrika founded | Advocates for land, reparations, sovereignty |

| 1969 | Fred Hampton forms the original Rainbow Coalition in Chicago | Multiracial alliance with Young Lords and Young Patriots; class-based solidarity against systemic oppression |

| 1971 | Assata Shakur joins Black Liberation Army | Symbol of armed resistance and exile |

| 1968 | African Peoples Party formed by former RAM members and other revolutionary nationalists. | Ideology: Revolutionary Black Nationalism – Unifies revolutionary nationalist forces under new banner |

| 1972 | Gary Convention (National Black Political Assembly) | Attempts unified Black political front |

| 1983 | African Liberation Support Committee dissolves | Marks shift from global solidarity to local organizing |

Editorial Distinction: Revolutionary vs. Cultural Nationalism

Revolutionary Black Nationalism seeks to dismantle capitalist and imperialist systems through armed resistance, international alliances, and counterstate institutions. It’s rooted in Marxist analysis, Pan-Africanism, and anti-colonial solidarity — exemplified by the Black Panther Party, Republic of New Afrika, and global figures like Malcolm X and Assata Shakur.

Cultural Nationalism, by contrast, emphasizes Black identity, heritage, and moral regeneration through cultural reclamation. It often avoids direct confrontation with the state, focusing instead on community uplift, traditional values, and symbolic sovereignty — as seen in the US Organization and the development of Kwanzaa. Leading cultural nationalist figures were Malauna Ron Karenga and Jitu Weusi of the East, in Brooklyn, New York.

While both currents affirm Black autonomy, Revolutionary Black Nationalism is insurgent and systemic, whereas Cultural Nationalism is restorative and symbolic. Their tension shaped the ideological landscape of the Black Power era.