Pig Foot Mary - Lillian Harris

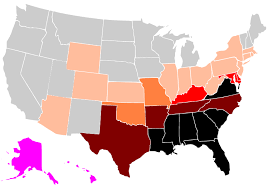

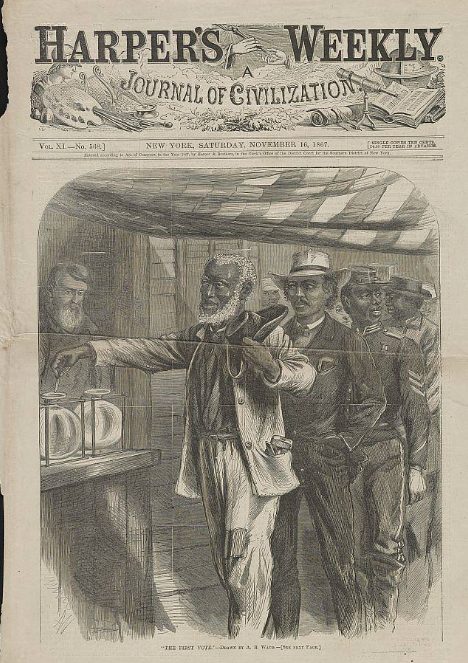

From a toddler carriage on a The huge apple avenue corner, she sold Southern food to African-American citizens who, fancy her, had moved to Unusual York in the end of the Wide Migration.

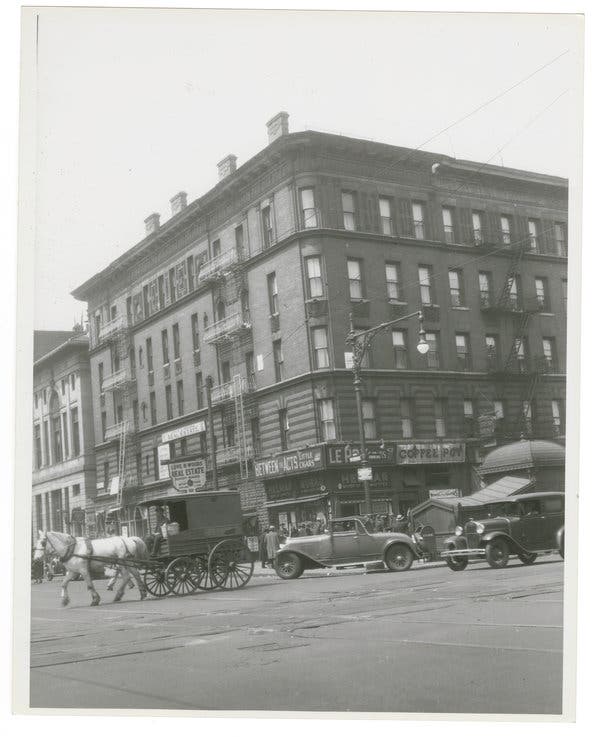

The corner of 135th St. and what’s now Malcolm X Boulevard in the 1920s, near where Lillian Harris sold her traditional Southern meals. Benja Kay Thomas played Harris in the play “Pigfoot Mary Says Goodbye to the Harlem Renaissance.”

Credit …NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black CultureIt’s fall, maybe October, in the early 1900s. On a bustling Manhattan street corner, Lillian Harris Dean stands in a starched gingham dress, her fingers resting on the handlebar of a baby carriage.

Harris Become Pig Foot Mary

“Pig’s feet!” she cries to passing neighbors, as she does in a play about her life written by Daniel Carlton. “A taste of down home for your weary bones.”

From the baby carriage — an early version of a food truck perhaps — Harris Dean sold traditional Southern meals: fried chicken, corn and, of course, pig’s feet, earnig herself the name, Pig Foot Mary. Her cooking soothed the palates of African-American transplants who, like her, had come to the unfamiliar metropolis in the purgatorial period between Reconstruction and the Great Migration.

She eventually built a name (Pig Foot Mary) and a fortune as a culinary entrepreneur and as a landlord, squarely planting herself in the history of Harlem. Before long her neighbors christened her “Pig Foot Mary,” the Madonna of the sidewalk.

“People talk about seizing an opportunity and finding a market — she did all of that,” Jessica B. Harris, a food historian and cookbook writer, said in a phone interview. She wrote about Harris Dean in “High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America” (2011).

Pig Foot Mary used her cooking as a path toward financial independence, taking hold of an informal culinary economy that has historically provided opportunities to women of color, from African-American caterers in the 1700s to churro sellers in today’s subways.

She marketed her food by tapping into the nostalgia of her customers, offering them a tether to the culture they missed as they tried to forget the legacy of slavery and servitude they had left behind.

“What she was doing,” Harris said, “was bringing the people the food of memory — the things they remember, the things they know.”

Soon, she traded in the baby carriage for a portable steam table that she had designed herself. After two years, she moved her business to Amsterdam Avenue between 61st and 62nd streets, where she stayed for 11 years. Business blossomed. She went from selling a dozen pigs’ feet a day to more than 100 a day and 325 on Saturdays. Though her cooking methods are lost to time, she most likely first boiled the pigs’ feet, which are similar in consistency to sausage, and then served them fried.

“As many as 25 customers have stood in line at her stand waiting to be served,” The Age wrote, adding that “she had people eating pigs’ feet who never ate pigs’ feet before.”

People came from as far away as New Jersey and Long Island just to try her cooking, the newspaper wrote.

In 1908, Lillian Harris married John Dean, an educated man from Lynchburg, Va., who had been a postal worker and owned a newsstand.

As Harlem became a hub for the thinkers, musicians and artists of the emerging Harlem Renaissance, she moved her business there in 1917 and worked on the corner of 135th and what is now Malcolm X Boulevard for 16 years. Like the famous street vendor in “Invisible Man,” Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel and ode to Harlem, the smell of her pigs’ feet cooking gave them a sense of belonging.

“She was saying to people, ‘This is your place,’” said Psyche Williams-Forson, the chairwoman of American Studies at the University of Maryland. “This street corner, this city, this part of the world. This is your place.” Williams-Forson wrote about Harris Dean in “Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, & Power” (2006).

Carlton’s play “Pigfoot Mary Says Goodbye to the Harlem Renaissance” was presented in 2011 by the Negro Ensemble Company and produced by the Metropolitan Playhouse. Benja Kay Thomas played the title character. Written entirely in verse, the play takes place on Harris Dean’s last day on the corner as she says goodbye to friends.

In researching her life, Carlton said in an interview, he found that Harris Dean “was somebody who talked to both the domestic workers and the people who were creating the culture.”

Around the corner from her stand, he said, A’Lelia Walker, the daughter of the beauty entrepreneur Madame C.J. Walker, hosted elaborate dinner parties as part of her Dark Tower salon.

“People like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston would come out of these fancy dinners and probably want some pig feet, some chitlins, some hog maws,” Carlton said.

Pig Foot Mary was also a minor character in “Hoodlum,” a 1997 film about Harlem in the 1920s starring Laurence Fishburne and Vanessa Williams. Harris Dean was played by Loretta Devine.

Using the money from her successful Pig Foot Mary stand, Harris Dean switched her focus to real estate, buying buildings and renting apartments during what became known as Harlem’s gold rush.

Most notably, she bought a five-story apartment building on the corner of 137th and Lenox Avenue for about $40,000 (about $650,000 today) and rented the units to tenants. She sold it six years later to an undertaker for $72,000 (about $1 million today).

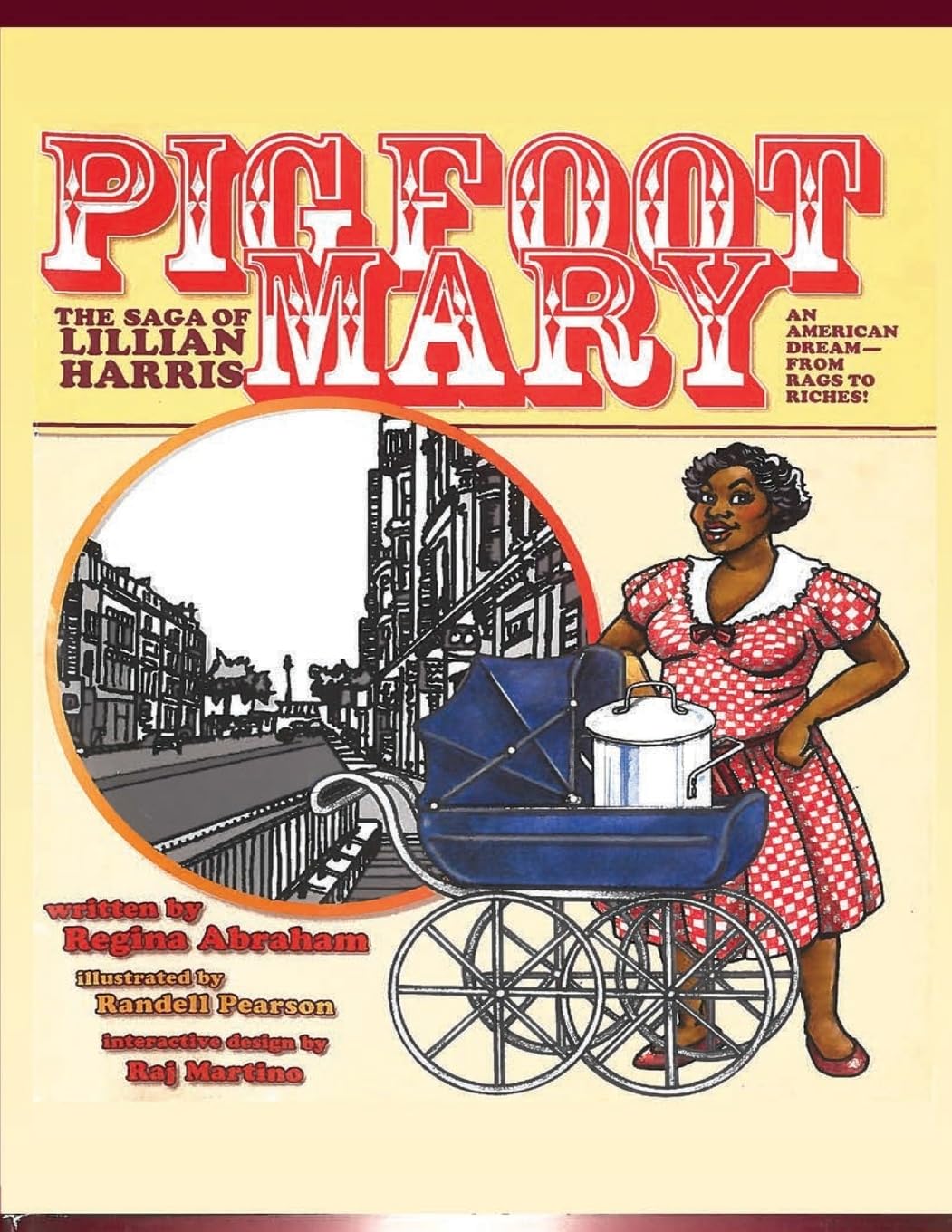

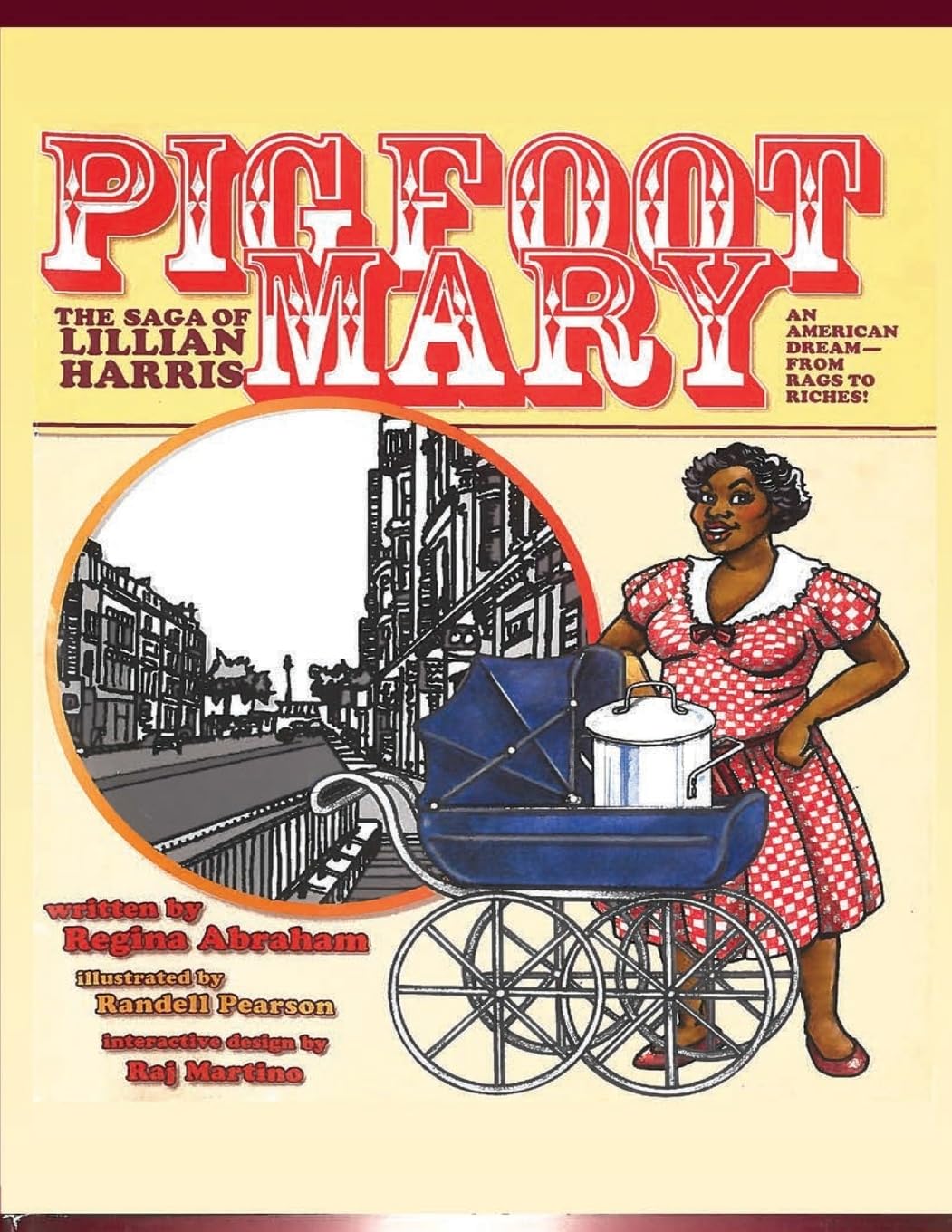

“She couldn’t read or write, but she could sure count her money,” Regina Abraham, who wrote “Pig Foot Mary: The Saga of Lillian Harris,” a children’s book published in 2011, said in an interview.

Today the buildings formerly owned by pig Foot Mary have become Harlem Hospital, a Salvation Army complex and St. Mark the Evangelist Church. And on the Harlem corner where she once sold pigs’ feet stands the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, an outpost of the New York Public Library.

Harris Dean became a philanthropist later in life. In 1927 she gained attention for cooking “an old fashion pigs’ feet dinner” for the Working Women’s League. An article in The Age about the event described her as “one of the wealthiest women in Harlem.”

She left New York in 1923 and traveled for six months, stopping in places like Yellowstone National Park and Los Angeles, The Age wrote.

She died, on July 16, 1929, in Los Angeles while visiting friends. By then she had amassed a fortune of $375,000 (about $5.5 million today).

Her body was brought back to New York, and hundreds came to the funeral. The Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church and the father of the future congressman, gave Pig Foot Mary her eulogy, praising her for “her business ability, her thrift and her desire to help her race.”

Jack Begg contributed research.