Black spending is not Black wealth

The Myth that Black Spending Equals Black Wealth

The tendency to equate black spending with black wealth is not based upon a realistic understanding of the American society and economy. The assertion that if African Americans would only pool its perceived $2.1 trillion consumer spending power that as a group, they would be one of the top 10 wealthiest nations in the world is a myth that ignores the fact that wealth is measured by assets not by spending, according to a professor who has written extensively on the subject.

The fallacy also ignores the fact that the U.S. government—along with Big Business, banking, and finance—shape and control the economy. Public policy, unfair taxation, discrimination and disinvestment in predominantly Black communities has exacerbated poverty and income inequality throughout Black America.

According to the Federal Reserve’s 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances, the median white household wealth is $285,000, yet the median household Black wealth of families is only $44,900. High spending with low wealth-building assets (homes, businesses, manufacturing, industry, retirement accounts, stocks) actually points to economic vulnerability.

African American Buying Power

The consumption metric has been popularized by well-meaning civil rights leaders, entrepreneurs, activists, ministers, chambers of commerce, advertisers, and marketers in Black communities for decades. The origin of the myth is often traced back to corporate marketing reports released by Nielsen and others that sought to highlight Black consumers as a lucrative, untapped market, not that African Americans were extremely wealthy.

African American buying power has grown 2.4 times since 2000 to $2.1 trillion, read the Diverse Intelligence Series by Nielsen. “With 48 million people, the Black community in the U.S. is young and growing in both size and economic impact. For advertisers looking to reach this powerful consumer segment, understanding who they are, what motivates them, how they consume media, and what pushes them to purchase is key to creating authentic connections.”

In an extensive Crusader interview, Dr. Jared Ball, professor of Media and Africana Studies at Morgan State University in Baltimore and author of “The Myth and Propaganda of Black Buying Power: Media, Race, Economics,” debunked and explained the myth’s origins, its impact on Black families, and offered solutions on how Black Americans can create true black wealth.

“This myth has been promoted by our Black advertising agencies, traditional media and leaders of our varying organizations for different reasons,” Ball explained. “Ad agencies and marketers use it to sell products and obtain accounts; the Black Press uses it to increase ad revenue; Black leaders to motivate economic solidarity or to chastise our people on our consumer habits; social media influencers use it to sell ‘get rich quick’ products, programs or other schemes; and mainstream corporations use it to tout their diversity efforts and enhance their brand loyalty with Black consumers,” Ball told the Crusader.

“At the end of the day, our people are being misled and (the assertion) is not rooted in economic, political, or social reality,” he said. “There are variations of this myth that also suggest that Black people are in the economic condition we are (collectively) in today because we lack financial literacy. Learning to save money or how to open a banking account are good things, but that has nothing to do with redlining, zoning, access to capital and the continuous racism, discrimination, bias, violence, and trauma inflicted upon our people.”

Comparing Black consumer spending to the gross domestic product (GDP) of nations such as Russia ($2.2 trillion), Canada ($2.1 trillion), South Korea ($1.7 trillion), or any African or Caribbean country without considering that African Americans (as a whole) control few resources, manufacturing, means of production, banking, finance, exports, or government revenue, is not sound. The GDP is a measure of all goods and services produced within a country in a year, and it includes government spending on infrastructure or the military, investments, exports, and consumption. It is output and productivity.

Black buying power only reflects consumer expenditures or what households spend on goods and services such as clothing, food, electronics, entertainment, vacations, technology, insurance, education, health care, transportation, legal and other professional services. It does not reflect production, national investment, or trade. Spending power is consumption.

Despite these facts, the myth of Black spending equating to Black wealth persists. Ball, who began debunking the issue in 2005 after hearing a presentation on Black economic progress that concluded with the admonition about pooling consumer dollars to generate wealth.

“I just remember thinking like this doesn’t make sense, and I just started looking into it,” Ball said. “This is propaganda, and it does work. Despite my efforts, it has been hard to get this message out, because even when presented with evidence, if the conclusions force someone to challenge their core ideological beliefs, it won’t work.

“(The propaganda) resonates for several reasons. It has financial incentive to circulate,” Ball continued. “It has an ideological incentive, and then it doesn’t challenge what we’re told so often about this country’s possibilities and that we can free ourselves and become equal without any meaningful political struggle.”

The professor has faced harsh criticism of his findings. “I will say that 100 percent of the public, overt criticism of my work has come from people who have demonstrated not having actually read the work,” Ball said, noting that everyone from hip-hop artists to Black Wall Street advocates to Black entrepreneurs and social media influencers have attacked him. “Usually, they’re responding to what they think I’m saying – and to my previous point, they’re also responding with a defense of their core ideological beliefs and sometimes class positions.”

When people read his book, Ball said, “even if they do not fully agree with it, they have a better understanding of the impact of this economic myth and may work with others to fully examine our socioeconomic and political position in this country – and offer solutions.”

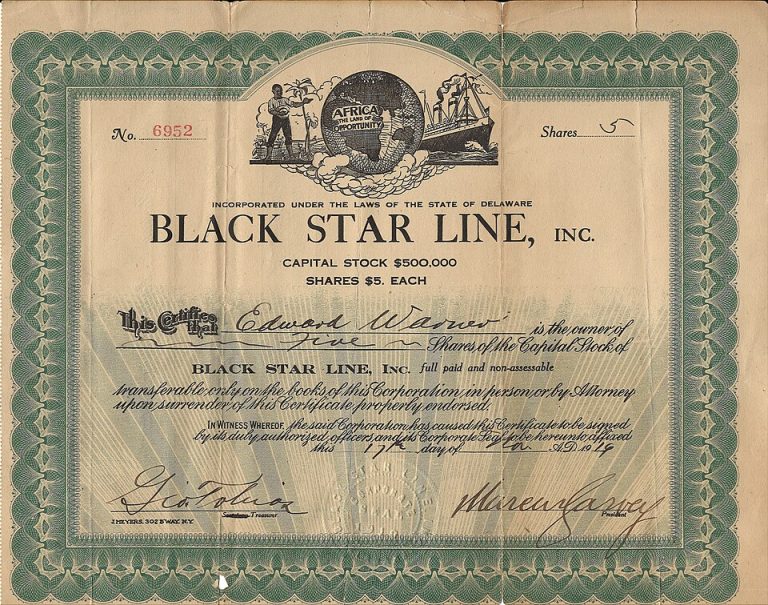

REPEATING THE PAST

If history is unbroken continuity, then it should be noted that Professor Ball is not alone in being criticized for attempting to debunk a Black American myth. In 1957 Howard University Professor E. Franklin Frazier wrote, “Black Bourgeoise,” a foundational critique of the African American middle-class. The work exposed what the sociologist claimed as illusions, contradictions, and limitations of the Black middle-class, particularly its failure to build true economic and political power.

The work was initially published in France in 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and months before the modern-day Civil Rights Movement began on December 1st of that year with Rosa Parks’ refusal to move to the back of a segregated city bus. Her defiance, sparked by the lynching of Emmett Till earlier that summer, led to the year-long Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Frazier argued that the Black bourgeoisie had become “trapped in a world of make-believe status, consumerism, and imitation of white values, rather than working toward substantive racial uplift. While chasing the so-called American dream, African American thought leaders, newspapers, magazines, churches, and business leaders had inadvertently failed to bring the masses of Black people who remained trapped in low-wage jobs or poverty toward the ladder of success.

The scholar noted that its most powerful institutions, such as the Black Press, the Black Church, and Black fraternal organizations, were the main cheerleaders of the myth of African American upward mobility. His research showed that businesses were often small and heavily dependent upon Black consumers, making them unable to compete with their white counterparts.

By “mimicking white society,” the Black middle class promoted status over substance by promoting materialism (cars, clothing, homes), respectability politics and illusive social clubs and “proper behavior, speech and religious formality,” Franklin wrote. The Black Church “reinforced fantasy, emotionalism, and materialism” rather than confronting social injustice directly.

The Black Press “pandered to the Black bourgeoisie’s fantasies about economic strength,” Franklin said, by often ignoring or downplaying the harsh realities of racism, crime, violence, economic exploitation, and systemic oppression. Instead, African American owned publications “contributed to this world of make believe” by celebrating trivial social news, highlighting job titles, promotions, and public appearances of high-profile individuals to create a “false sense of progress” while the majority of Blacks suffered.

Publishers of Black-owned newspapers, which had historically been at the forefront of advocating for racial justice, economic inclusion, equal protection under the law and civil rights, were livid and denounced the book on their pages. Bookstores refused to carry it.

“The reaction of the Negro community is understandable when one realizes the extent to which the book created the shock of self-revelation, … and intense anger,” Franklin wrote in the preface of the book’s later edition. “This anger was based largely upon the feeling that I had betrayed Negroes by revealing their life to the white world.

“I was attacked by some Negroes as being bitter because I had not been accepted socially and by others as having been paid to defame the Negro,” Frazier said. “In one Negro newspaper there was the sly suggestion that Negroes should punish me for being a traitor to the Negro race.”

Black Bourgeoisie was published more than a decade before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in a conspiracy involving U.S. military snipers, the Memphis Police Department, James Earl Ray and others, after he demanded a guaranteed income for all Americans and a substantive war on poverty via a “Poor People’s Campaign.”

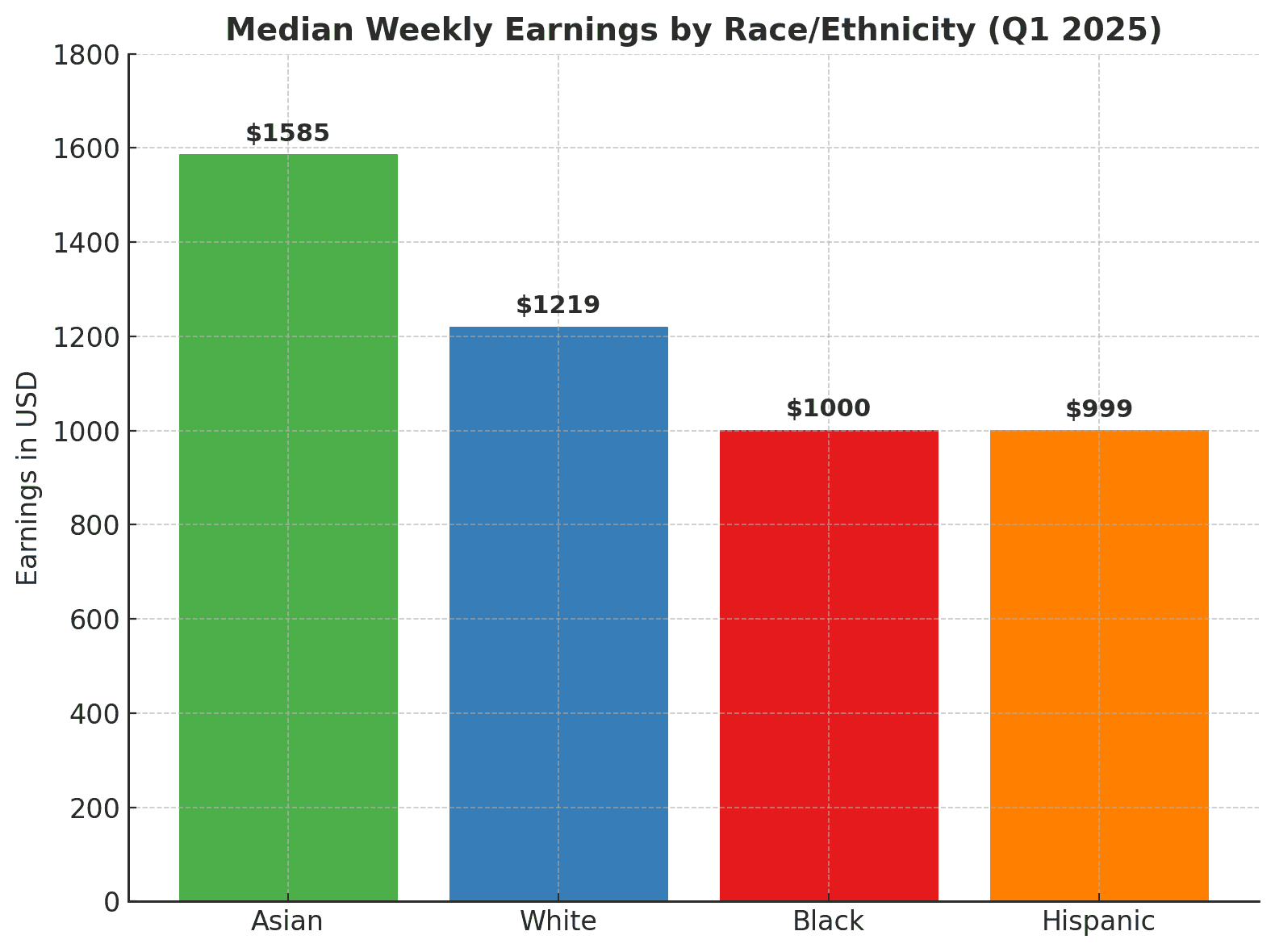

At the time of King’s murder, the average Black median income was $5,540 in 1968 compared to $8,810 for white households during that period, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Though educated African Americans had begun to build a middle-class, most Black workers were domestics, low-wage day laborers, sharecroppers, janitors, cooks, tradesmen, or unemployed.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for the first quarter of 2025 noted the median weekly earnings for full-time wage and salary workers are $1,585 for Asian, $1,219 for, $1,000 for African Americans, and $999 for Hispanics or Latinos. Despite Black collective spending power, workers earn approximately 82 percent of what whites earn. The wage disparities are influenced by education, vocational skills, occupation, work experience and potential systemic biases in the labor market.

Despite wage disparities, which indicate the average Black worker earns less than whites, another prevailing myth is that the earnings “circulate once” in Black communities while other groups “circulate their dollars six-to-12 times in white or Asian neighborhoods.” It implies that as soon as African Americans are paid, they rush to spend their money outside of their communities and mostly with other racial groups.

Ball and fellow researchers have said there is no data to substantiate the oversimplified claim. There has been no government data from the Census or the Federal Reserve that has tracked how long a dollar stays in different racial communities. Black consumers are more likely to spend money outside of their community because of fewer Black-owned retailers, service providers, banks, and other services operating within their neighborhood boundaries. The issue isn’t spending habits; it is structural barriers and the undercapitalization of Black-owned businesses.

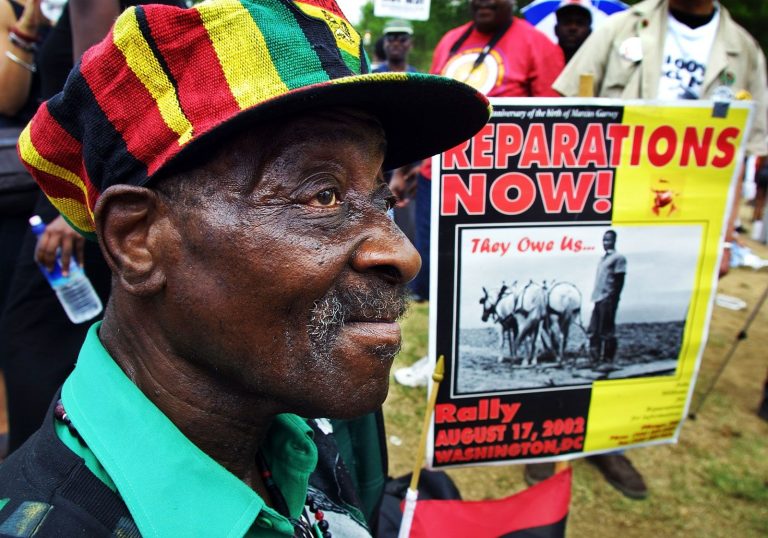

TOWARD A SOLUTION

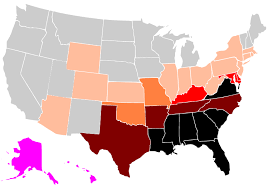

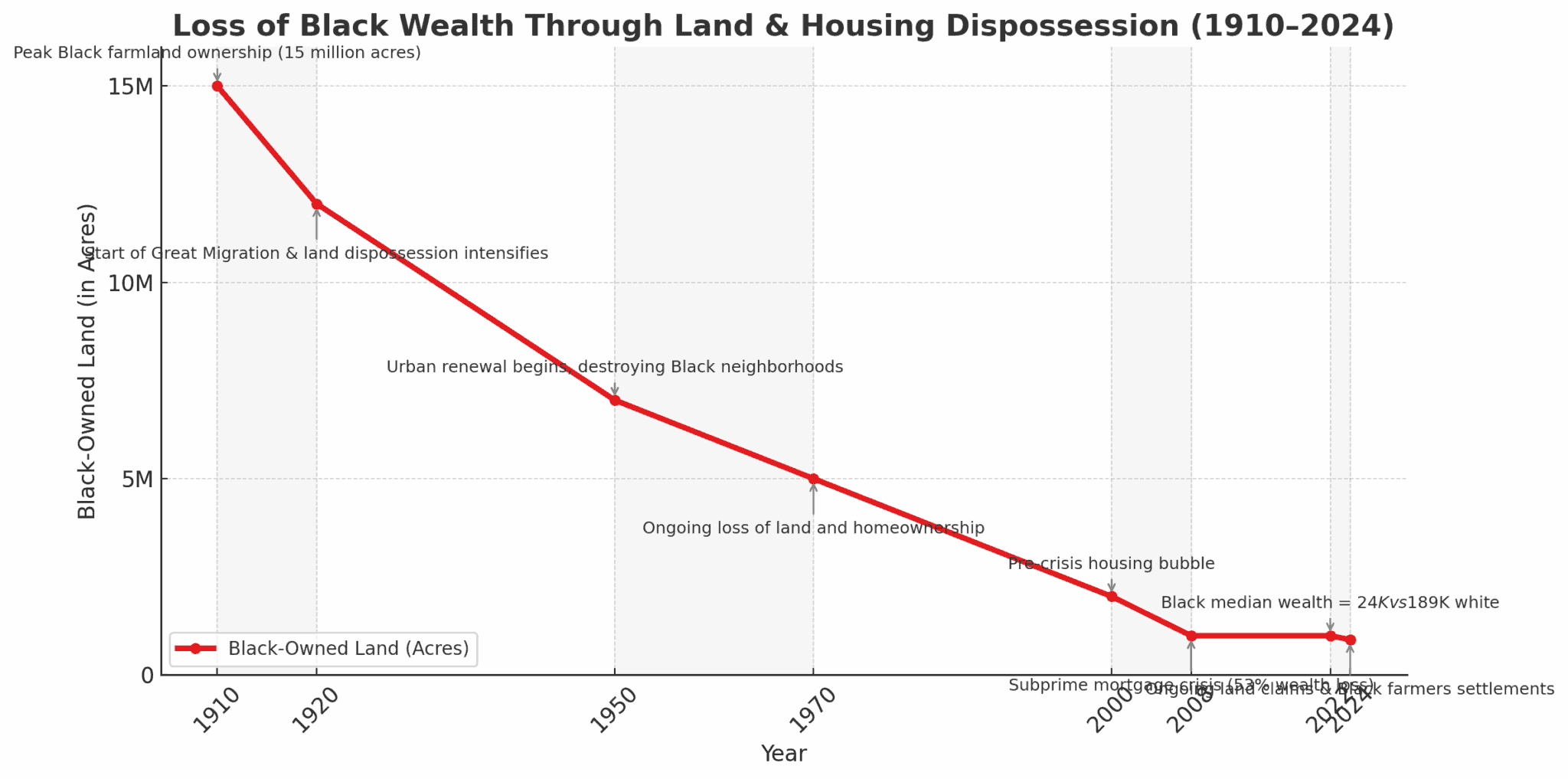

Twenty years of so-called “urban renewal” led to the greatest destruction of Black-owned property between 1950 and 1970. It was implemented by the federal government through the Housing Act of 1949. Over 1,600 Black neighborhoods across the U.S. were bulldozed for highways, university expansions and revitalization projects. Hundreds of thousands of Black families in Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, Atlanta, St. Paul, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, lost homes and businesses and decades of accumulated generational wealth.

In addition to urban renewal, African Americans continued to experience redlining and became targets for predatory lending. Southern Black landowners and farmers lost millions of acres of land. In 1910, African Americans owned 14 million to 15 million acres of farmland (14 percent of all U.S. farmland); however, by 2024, ownership had been reduced to less than two million acres (a loss of about 90 percent of their farmland over the course of the 20th century).

Scholars estimate the economic loss from $250 billion to $350 billion in today’s currency. In 2022, The Land Loss and Reparations Project estimated the total value of Black land loss due to discrimination, theft, and violence alone to be worth $326 billion. Had African American farmers “pooled their consumer dollars,” they still wouldn’t have been able to stop the loss of their lands, because much of it was accelerated by racist federal and local government policies.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) routinely denied loans, crop subsidies and disaster relief that white farmers received. A 1999 class-action lawsuit revealed the USDA had systemically discriminated against Black farmers for decades. Local officials throughout the South were shown to have delayed, denied or tampered with Black farmers’ applications to drive them into foreclosure.

As the world celebrated the election of Barack Obama as the 44th U.S. president and the first of African heritage in 2008, Black Americans were experiencing the greatest transfer of wealth and financial loss during the subprime mortgage crisis. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 53 percent of Black wealth in the U.S. was destroyed between 2007 and 2010. By contrast, only 16 percent of white wealth was wiped out. Latinos reportedly lost 66 percent of their wealth.

“Between 2007 and 2010 alone, Black Americans lost over half their total wealth, a collapse engineered by predatory lending and systemic racism,” the Pew Research Center reported in 2011. No major bankers were criminally prosecuted despite widespread evidence of mortgage fraud, deceptive business practices, predatory programs, and misleading investors about bundled mortgage securities.

When it came time for the government to act, the banks, insurance companies, and auto manufacturers received hundreds of billions of dollars in federal bailouts through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), while millions of American homeowners, especially Black and Latino families, were left to their own devices.

According to the U.S. Treasury Department, TARP injected $700 billion into the economy with $182 billion to AIG (insurance); $45 billion allocated to Citigroup; $45 billion to Bank of America; $25 billion to JPMorgan Chase; and $25 billion to Wells Fargo, among others. Troubled homeowners were encouraged to renegotiate their mortgages, but only one million received permanent modifications while the majority were denied relief or re-foreclosed.

In 2020, the Brookings Institute released a study, “The Devaluation of Black Assets,” that found that if Black-owned businesses had the same access to capital as white-owned businesses, they could create over one million new jobs. As of March 2025, the U.S. unemployment rate stood at 4.2 percent, with notable disparities among racial and ethnic groups: White unemployment was 3.7 percent; Black at 6.2 percent (1.7 times higher than white workers); Hispanic/Latino at 5.1 percent; and Asian at 3.5 percent. About 12.3 percent of Black youth are unemployed versus 8.5 percent of white teens.

Beyond examining dire statistics and recalling lessons from history, Ball says African Americans must begin to organize and have meaningful discussions about our way forward. Solutions include continuing to acquire assets, creating and owning manufacturing and distribution companies, and reexamining the meaning of political power. These things should be done in addition to continuing to support our businesses and entrepreneurs.

He noted that voting in and of itself is not the answer. The professor said Blacks should move to consolidate their voting power, independent of the two-party system, in order to elect officials who will address their economic concerns with public policy solutions enforced by federal law.

“I agree we do need political power,” Ball told the Crusader. “ I think our only solution is in public policy that redistributes wealth. This idea that the Black community, or any community, can grow wealth solely on the backs of small businesses, along with other mythologies about circulating the Black dollar … or what Black entrepreneurialism can do – will only continue to deny us our real power.”

Noting that between 1992 and 2012, African Americans created more than two million businesses, Ball says national sales revenue went down from 1% to less than half a percent. He says this indicates the solution to Black economic progress does not lie in opening businesses or financial literacy but in being in a position to secure public policy that ensures financial stability and people’s ability to create and maintain generational wealth.

“We must organize political movements that don’t require the levels of money that we’re told is required,” the professor said. “They just require more participation. So instead of telling us to start businesses and circulate our dollar and save our money, we should be advocating for policy that says ‘we’re a 70 percent consumer-based economy in this country. Our consumption should be rewarded by redistributing that $27 trillion GDP to benefit us through free health care, guaranteed employment, free education, debt relief, and so on.”

Stephanie Gadlin is an award-winning author and investigative journalist whose work blends historical analysis, data reporting, and cultural commentary. She specializes in uncovering the intersections of Black culture, public health, environmental justice, systemic racism, and economic inequality—covering stories from the United States to Africa and the Caribbean. For confidential tips, please contact: [email protected].