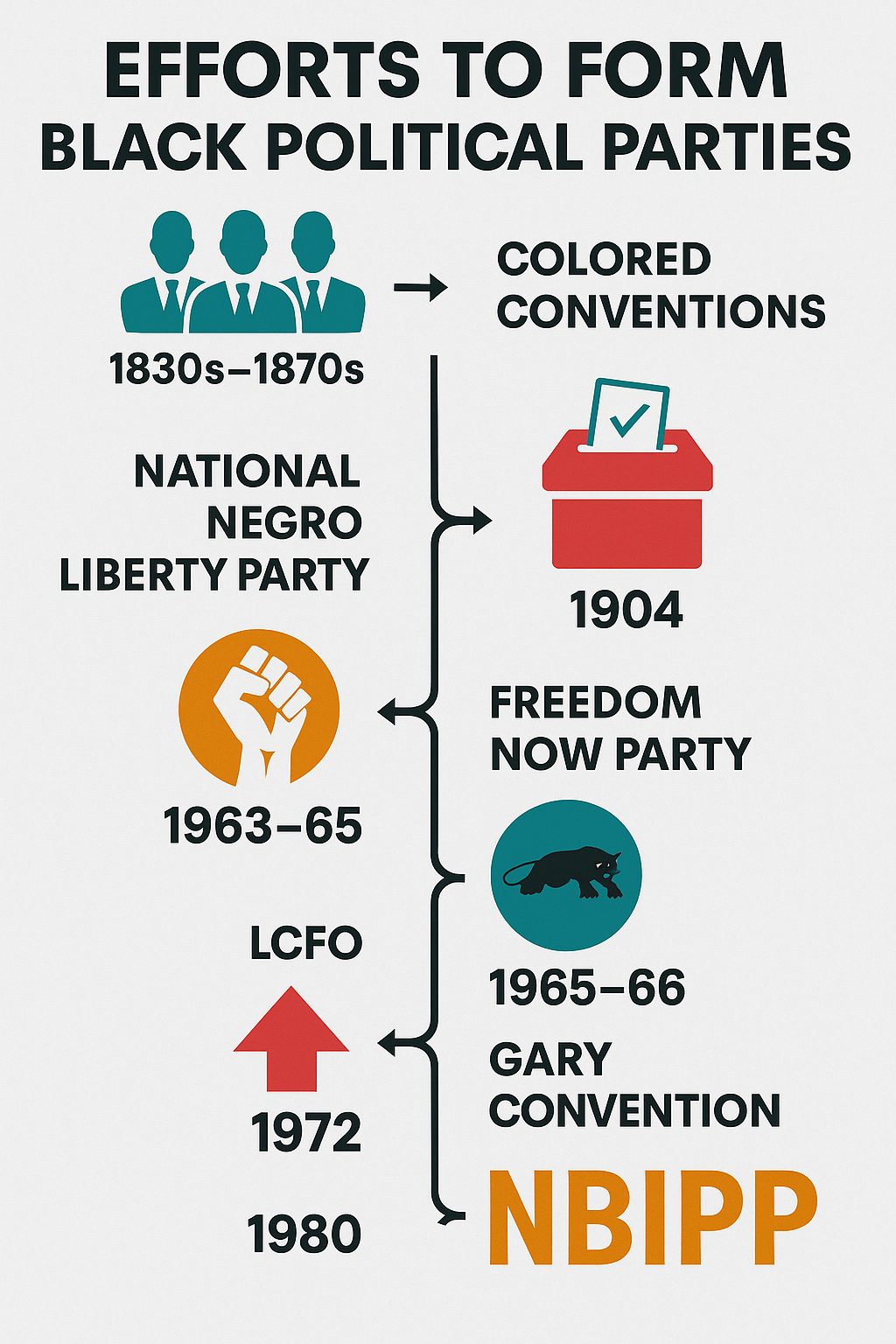

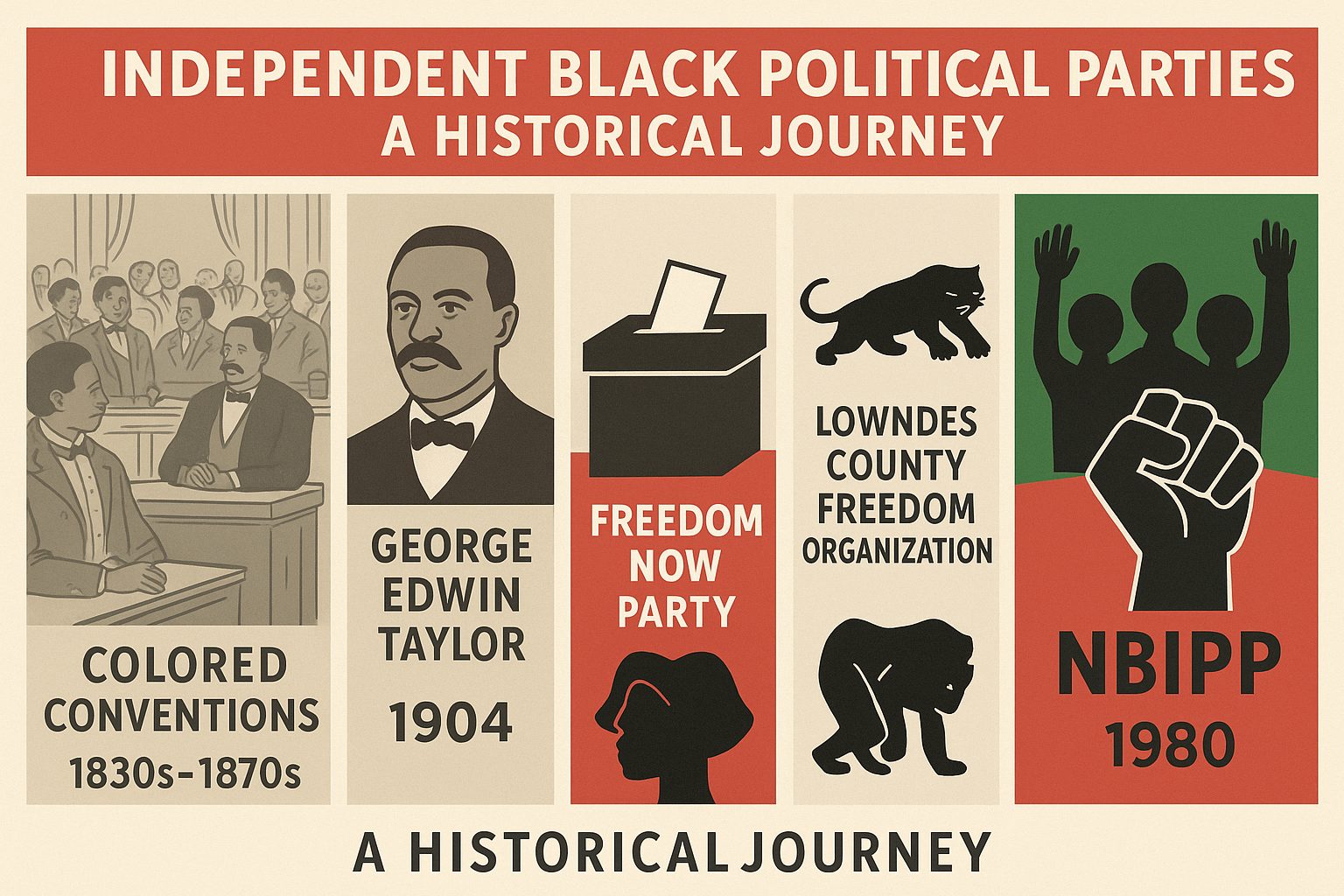

Timeline of Historic Efforts to Form a Black Political Party

📚

1) Overview: The Long Push for Independent Black Political Power in the US

Efforts to build independent black political parties and black political power in the USA go back as far as the enslavement of African Americans. From antebellum “Colored Conventions” to the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, and the 1980 launch of the National Black Independent Political Party (NBIPP), African Americans have repeatedly explored, attempted, or actually built independent political vehicles outside the two major parties. These efforts aimed to secure representation, policy leverage, and protection against racial violence and disfranchisement when the major parties failed to do so. At times, the explicit goal was to in fact build a black political party. Colored Conventions Project+1

2) Antebellum and Reconstruction Roots: Conventions, Coalitions, and the First National Projects

The Colored Conventions Movement (1830s–1870s)

Beginning in 1830, free and formerly enslaved Black leaders convened state and national conventions to craft strategies for civil rights, mutual aid, migration, education, and political self-defense. These gatherings did not found a lasting national party, but they created the infrastructure, networks, and agenda that later efforts at building independent black political parties drew upon. Colored Conventions Project+2exhibits.library.cornell.edu+2

Reconstruction: Biracial Coalitions and Early Factionalism

After the Civil War, Black voters organized through Union Leagues and allied with Republicans across the South. As the white supremacist backlash mounted, “lily-white” Republican factions sought to purge Black leadership, weakening space for independent Black politics inside the GOP and nudging activists to consider separate vehicles. Wikipedia+1

The 1872 National Colored Convention in New Orleans

A major national convention of Black leaders met in New Orleans in 1872 amid Reconstruction crises. Delegates debated national strategy—civil rights enforcement, office-holding, and the merits of independent political organization—foreshadowing later third-party experiments. Encyclopedia Virginia+1

3) Turn of the Century: The National Negro Liberty Party (1904) and Presidential Ballot Ambitions

In 1904, journalist and activist George Edwin Taylor accepted the presidential nomination of what was variously called the National Negro Liberty Party / National Negro Civil Liberty Party—an early national black political party founded “by and for” African Americans. Ballot access barriers and repression meant Taylor’s campaign could not get on official state ballots; nonetheless, it signaled a bid for truly independent national power when both major parties were retreating on Black rights. Wikipedia+2Encyclopedia of Arkansas+2

Why it mattered: The Taylor campaign illuminated structural obstacles that would be faced by black political parties and other third parties in the US. These obstacles, state ballot laws, press hostility, and organized white resistance, would dog later efforts by African Americans to organize an independent black political party.

4) Mid-20th Century Experiments: Freedom Now Party and Local Breakthroughs

Freedom Now Party (1963–1965)

Launched during the March on Washington era, the Freedom Now Party (FNP) sought to put independent Black candidates on the ballot in several states (notably Michigan, New York, Connecticut, D.C.). Despite strong rhetoric and notable figures (e.g., Rev. Albert Cleage), FNP won few votes and soon dissolved, but it offered a template for ballot-qualified, Black-led politics outside the major parties. Wikipedia+1

Lowndes County Freedom Organization (1965–1966)

In Alabama’s “Bloody Lowndes,” local activists and SNCC organizers built an independent county party with the black panther as its ballot symbol—explicitly avoiding George Wallace’s segregationist Democrats (white rooster). LCFO proved that independent Black tickets could mobilize, educate voters, and capture offices—though success remained vulnerable to state repression and structural constraints. Wikipedia+1 The organizing of the Black Panther Party was, in part, inspired by the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Through an agreement between Stokley Carmichael of SNCC and Max Stanford of RAM, the Black Panther was chosen as the symbol for the first Black Panther Party organized in New York.

5) The 1972 National Black Political Convention (Gary, Indiana)

From March 10–12, 1972, some 8,000–10,000 delegates and observers convened in Gary, Indiana, to debate a national Black agenda and the relationship to the two parties. The convention issued the Gary Declaration, asserting that the American political system had failed Black communities and elevating arguments for “independent Black politics”—whether inside or outside the parties. The convention prioritized increasing Black office-holding and building unified leverage on policy. Encyclopedia Britannica+2Wikipedia+2

Legacy: Gary did not found a single national party, but it gave strategic coherence to independent-minded organizing and fed directly into later efforts, including NBIPP.

6) National Black Independent Political Party (NBIPP), 1980–mid-1980s

In November 1980—amid disillusionment with both parties—activists launched the NBIPP at a Philadelphia conference (≈1,500 participants). The chair of the founding convention was Ron Daniels, who had served as president of the National Black Political Assembly from 1974 through 1980. The party sought a durable national vehicle to contest elections, develop cadre, and negotiate power from outside Democratic and Republican structures. NBIPP struggled with funding, ballot access, and internal cohesion; it dissolved after several years (mid-1980s), but remains the most ambitious national attempt at an independent Black party in the late 20th century. Black America Web+1

While NBIPP, the National Black Independent Political Party, attracted major leading and credible African American intellectuals, theoreticians, and leaders, it also attracted all of the then functioning black nationalists and revolutionary black nationalist formations, and virtually every left of center and radical organization in the USA. All of the leftists groups sent their leading black cadre members into NBIPP and the NBIPP founding conferneces and organizing meetings across the country in what became a vicious struggle with the indigenous black community organizations for hegemony and power inside the emerging black political party. These competing forces were too much for an eembryonic black political party to withstand.

7) Related State and Regional Vehicles: What Worked—and Why

Biracial “Fusion” and the Readjusters

- Readjuster Party (Virginia, late 1870s–1880s): A biracial coalition that won state power, refinanced public debt, protected schools, and elected William Mahone to the U.S. Senate—demonstrating that independent/third forces could govern when coalitions held. Encyclopedia Virginia+1

- Fusion (North Carolina, 1890s): Republicans and Populists (with significant Black support) won statewide power—until the 1898 Wilmington coup and massacre violently ended the experiment. The episode shows how extra-legal violence crushed coalitional gains. NCPedia+2Encyclopedia Britannica+2

8) Why Many Efforts Failed—or Fell Short

- Ballot-access and election law barriers: State requirements for signatures, filing fees, and party recognition made it costly to get on ballots nationally (e.g., Taylor 1904; FNP 1964). Wikipedia+1

- Racial terror, disfranchisement, and state repression: From the post-Reconstruction “lily-white” purge to the Wilmington coup, violent suppression curtailed independent power. Wikipedia+1

- Resource constraints: Independent campaigns lacked donor networks, media access, and institutional funding that major parties command (recurring from FNP through NBIPP). Wikipedia+1

- Strategic divisions: Debates over “inside vs. outside” strategies (influencing Democrats vs. building separate parties) often split leadership and base after milestones like Gary 1972. Wikipedia

- Winner-take-all electoral rules: Single-member districts and first-past-the-post systems penalize third parties; local wins (LCFO) proved more feasible than sustained national representation. Wikipedia

- Competing forces: Ideological struggles and struggles for hegemony between black and non black led forces and intra black community struggles between and among cultural nationalists versus revolutionary nationalists and those who understood the history of African Americans engaging in electoral politics and those who did not or favored an exclusively mass action approach.

9) What Succeeded—and What Endured

- Agenda setting and cadre formation: Conventions (1830s–1870s; 1972) and parties (FNP, LCFO, NBIPP) trained organizers, shifted public debate, and seeded future officeholders—even when the vehicles folded. Colored Conventions Project+1 Major leaders and architects of Jesse Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 Presidential campaigns – Ron Daniels, Ron Walters, and others, (campaigns which ultimately changed the Democratic party and American Presidential politics and led to the election of Barack Obama as the first African American President) were NBIPP veterans.

- Local governance footholds: Independent or fusion structures sometimes captured city/county offices, delivering tangible policy (schools, safety, voting access) and proving capacity to govern. Encyclopedia Virginia

- Symbolic power: LCFO’s black panther symbol influenced later Black political iconography and organizing. SNCC Digital Gateway

10) Counterfactual: If a National Black Party Had Endured, Could It Co-Exist with the Two-Party System?

Short answer: Yes—but likely as a hybrid that combined independent ballot lines with coalition tactics.

- Ballot-fusion and cross-endorsements: In states that allow fusion, a Black independent party might endorse candidates on its line, preserving autonomy while shaping slates—similar to how minor parties in some states influence major-party nominees. (Feasible at state/local level; nationally constrained.)

- Inside/outside leverage: A standing party could negotiate platforms, appointments, and budgets with Democrats (and occasionally Republicans) while running its own candidates where the major parties ignored Black interests—an institutional version of Gary’s “independent Black politics.” Wikipedia

- Issue and city power base: Concentrating on municipalities and counties with large Black electorates could build durable governing records first, then scale strategically—echoing LCFO lessons and Readjuster/Fusion precedents. Wikipedia+1

- Likewise, in cities where black mayors have been elected due to very large African American populations, candidates willing to go beyond the constraints of the two party system and pursue a model similar to the one followed by Zohran Mamdani in his candidacy for mayor of New York City, could succeed in cementing a power base for an independent black political party that works in coalition with other groups’ interests.

Limits remain: First-past-the-post rules, fundraising gaps, and media ecosystems still penalize third parties; enduring success would likely hinge on (1) municipal and regional strongholds, (2) fusion where legal, and (3) disciplined negotiation with major parties between election cycles.

However, within the African American organizing experience, two solid examples stand out as models for an embryonic fundraising and financial base. If we apply today’s technology to the successes of these two efforts, there’s a parth to be followed for independent financing of a black political party. Those two examples are the fundraising and financing of the Garvey Movement and the independent economics of the Nation of Islam.

11)

Concluding Analysis – From Reconstruction to Obama: Lessons in Black Politics

Across two centuries, independent Black political efforts have recurred whenever the major parties failed to protect rights or deliver representation. The most ambitious national bids—1904 Taylor campaign and 1980 NBIPP—revealed structural barriers, while local and coalition models (LCFO, Readjusters, Fusionists) achieved measurable gains before repression or institutional headwinds reversed them.

The 1972 Gary Convention stands as a strategic fulcrum, arguing for independent Black politics—not necessarily a fully independent national party everywhere, but a tactical stance that could oscillate between “inside” participation in the Democratic Party and “outside” organizing to maximize leverage. Out of Gary grew the momentum that produced the National Black Independent Political Party (NBIPP) in 1980, as well as a broader consciousness about the necessity of a unified Black political agenda.

The NBIPP’s ambitions were ultimately cut short by structural barriers, financial challenges, and fragmentation, but its spirit fed directly into the Jesse Jackson presidential campaigns of 1984 and 1988. Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition broadened the vision beyond an exclusively Black base, yet still anchored itself in Black political strength. Although Jackson remained within the Democratic Party, his campaigns altered the Democratic Party’s DNA: rules for delegate allocation shifted to give minority and grassroots voices greater weight. This institutional change laid groundwork not only for expanded Black representation in the 1980s and 1990s but also for the historic election of Barack Obama in 2008—an outcome that would have been nearly unthinkable without the reforms Jackson forced.

We can only speculate on what might have happened if Jackson had chosen to build an independent Rainbow Party in the mid-1980s. With the Black community as its anchor and multiracial alliances around labor, Latinos, Native Americans, women, and progressives, such a party could have been the most serious third-party bid since the Progressive Party of 1912. What we do know is that Jackson demonstrated both the possibility of a multiracial independent movement and the costs of remaining tethered to the Democratic establishment.

This tension—whether to reform the system from within or break out independently—echoes the dilemma faced during Reconstruction. African American electoral success in the 1860s and 1870s was so profound that it triggered a sweeping white backlash: paramilitary terror, voter suppression, gerrymandering, and eventually Jim Crow laws designed specifically to crush Black political autonomy. That backlash made clear that Black independent power was perceived as a fundamental threat to the racial order.

Thus, across two centuries, the story repeats: when African Americans gain meaningful electoral footholds — whether through Reconstruction legislatures, fusion politics in the 1890s, Gary 1972, NBIPP, or Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition — the broader system adjusts, sometimes violently, to limit or reabsorb that power. The pattern persists into the present: the election of Barack Obama was followed by a wave of voter suppression laws, the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), and the rise of Trump-era policies that explicitly targeted Black political and economic infrastructure — from attacks on DEI frameworks and HBCU funding pipelines to federal interventions in majority-Black cities under the guise of “law and order.” The current Supreme Court’s narrowing of affirmative action and its willingness to entertain challenges to the Voting Rights Act signal a judicial turn that echoes earlier legal rollbacks of Black political gains. Yet each effort leaves behind institutional legacies — church networks, funding models, organizing cadres, party rule changes — that form stepping stones for the next generation.

Financing An Independent Black Political Party

The unanswered question remains: could a disciplined, well-financed independent Black political vehicle coexist with America’s two-party system? The evidence suggests it would require not just electoral mobilization, but the same kind of economic base pioneered by Garveyism, the Nation of Islam, Civil Rights churches, and community-centered groups like the Black Panthers. Without financial independence, electoral independence remains elusive. But with it, the dream of a durable, independent Black political force—rooted in history yet adapted to the digital age—remains within the realm of possibility.

The Garvey Movement and The Nation of Islam

Within the African American organizing experience, two solid examples stand out as models for an embryonic fundraising and financial base. The Garvey Movement, through its dues-paying membership and business ventures, and the Nation of Islam, through its disciplined economic independence, demonstrated that large-scale Black-led financing was possible outside traditional political structures. If we apply today’s technology—online crowdfunding, digital organizing, and peer-to-peer fundraising—to these historic models, we see a clear path toward sustaining an independent Black political party. Additional lessons can also be drawn from the Civil Rights era’s church-based fundraising networks and the Black Panther Party’s community programs, which linked resources directly to grassroots legitimacy.

September 25th, 2025