The release of the biopic Harriet introduces audiences to an exploration of the woman who rescued enslaved men, women and children from terror and suffering.

In the early morning hours of Aug. 28, 1955, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam arrived at the Mississippi home of Moses Wright, demanding he turn over his 14-year-old nephew, Emmett Till. Armed with a pistol, the two white men kidnapped the teenager, and then murdered him. Till’s death would become a key turning point in the civil rights movement, in part because Wright did what no one expected: he stood up in court and accused Bryant and Milam of the gruesome crime.

But before the moment came for him to testify, Wright sent his wife and children to Chicago, understanding that it was simply too dangerous to keep his family in Mississippi. Wright knew that by standing up to state-sanctioned violence against black people, he would trigger his own execution. So, in his mid-60s, Wright took to the stand and accused Milam and Bryant of the violent crime—and then, to save his own life, he left behind just about everyone and everything he knew, quickly leaving the state to escape the trauma and violence of the South.

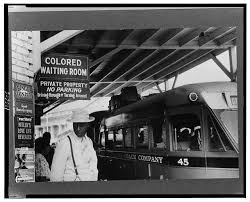

For African Americans, there is a long history of leaving family and friends behind, going elsewhere in search of safety. At the turn of the 20th century, decades before Wright’s testimony, African Americans fled from the violence of the South for opportunity in northern and western cities in a movement that became known as the Great Migration. But perhaps the most symbolic example of African Americans fleeing state-sanctioned violence features the Underground Railroad. A loosely connected system of safe havens, the Underground is given credit for shuttling tens of thousands of enslaved fugitives out of the South to non-slave holding states and Canada. Sitting at the center of this history is abolitionist and women’s rights activist Harriet Tubman Davis.

There is a negative connotation linked to flight. To run away is often seen as a cowardly thing to do. “Fight” and “flight” are opposites and those who flee are often seen as taking the easy way out; those who stay for the battle are brave. But hundreds of years of African American history belie that simplistic notion. Running can be just as brave as going to battle—and, in fact, they can be the same thing. If anyone knew the power behind fighting and flight, it was Tubman.

Biopic Harriet Chronicles Life of Harriet Tubman

With the release of the biopic Harriet—written, directed and produced by a heavy-hitting team of black women filmmakers—audiences across the world will be introduced to an updated and multi-dimensional exploration of the woman who rescued enslaved men, women and children from certain terror and suffering. For almost a decade, Tubman put her own safety aside each time she ferried fugitives to safety. She was an indomitable leader who had her God and her Harriet Tubman gun as her only weapons.

The harriet Tubman gun features prominently in advertisements for the movie. Across the several varieties of posters and trailers, there are a few common threads: there’s Cynthia Erivo as Tubman, there’s her unyielding stare and there’s her gun. Tubman’s own narrative—written by Sarah Bradford, based on interviews, and published in 1869—explained the obvious need to carry a pistol. Not only was she in danger of being captured or murdered during her time as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, but she also needed her weapon to convince weary and frightened fugitives not to give up and turn around. Tubman wasn’t the only one carrying a gun during her missions—some of the men and women in her care would have stolen firearms from unsuspecting enslavers. They too understood that their flight was a fight.

Cynthia Erivo stars as Harriet Tubman and Aria Brooks as Anger in HARRIET, a Focus Features release.

Glen Wilson—Focus Features

But Tubman was still unique. The facts surrounding her life are so incredible they seem almost impossible to believe. Born Araminta Ross some time around 1822 on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Harriet lived through and witnessed the violence of slavery—the selling of her sisters, the brutal beatings of enslaved people, and the death and destruction that clung to slavery’s cloak. Her marriage to a free man, John Tubman, and her close relationship with her family were threatened in 1849 when she learned that she would be sold. After an aborted runaway attempt with her two brothers, Harriet escaped to the Pennsylvania border in the fall of 1849.

Having made it to freedom, for the close to ten years that followed, she repeatedly traveled back to Maryland to rescue her friends and family. She traveled by train and by foot through the marshy Eastern Shore to save her loved ones from torture. Her first return trip to Maryland was to orchestrate the rescue of her niece from a slave auction—the beginning of a sterling record of leading the enslaved out of bondage. Each time she went South, she did so with great urgency, often to protect a loved one from arrest or sale.

Tubman was unflinching in her commitment to liberation and would use the power of her pistol if necessary. Later in life, Tubman stated, “I had reasoned this out in my mind; there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty, or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other[.]”

She knew that the law was not on her side, evidenced by the federal government’s support of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which gave enslavers had the right to travel to any state in search of their human property, leaving no American city or town a safe haven for fugitives. Tubman knew that the only way to save her loved ones was to make them disappear.

It would take a war to destroy the system of slavery. Until that day arrived, Tubman helped her people steal away, one or a few at a time. She made 12 or 13 trips to Maryland and rescued nearly 70 people, defying federal law with each mission. In speaking engagements across northern cities she condemned the law of the land, taking aim at the system of slavery and the lawmakers who continued to condone it. After each speech she would disappear into a world of shadows inhabited only by fugitives and their allies.

Tubman knew then, as we know now, that in the absence of justice, running away is sometimes the only way to save a life.

Erica Armstrong Dunbar is the author of the book She Came To Slay: The Life and Times of Harriet Tubman.

Contact us at [email protected].