Southern Regional Council Institutional Arc Timeline

The Southern Regional Council and the Making of Black Political Power in the South

The Southern Regional Council (SRC) has been one of the most consequential — and often quietly influential — institutional actors in the transformation of Black political life in the American South across the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty‑first. Working as an intermediary between philanthropic capital, grassroots activists, legal advocates, and lawmakers, SRC’s programs, publications, and funding channels helped convert waves of voter registration into durable electoral power. The Council’s Voter Education Project (VEP) and the later Voting Rights Programs stand out as the twin engines that both expanded the Black electorate and helped force structural reforms — including the creation and defense of majority‑Black districts across municipal, county, judicial, school board, state legislative, and congressional maps — that made Black officeholding possible on a scale previously unimaginable in much of the region.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Southern Regional Council assisted “in redrawing the political boundaries in over 2,000 jurisdictions in the South.” — Statement and testimony presented by Selwyn Carter of the Southern Regional Council on behalf of the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus to the Joint House/Senate Reapportionment Committee Hearing, July 31, 1995

This feature documents SRC’s institutional arc, chronicles VEP and the Voting Rights Programs, traces named examples of officials and districts whose emergence was enabled by SRC’s work, explains how the organization’s publications and technical support shaped litigation and policy, and signals archival touchpoints and quotations to support further sourcing. Where primary‑source citations and direct archival quotations would strengthen the account, I remain open to feedback from researchers and movement participants. I’ve added some from available copies of Southern Changes and the Voting Rights Review, and related archival collections.

🏛️ Institutional Personnel: Directors, Staff, and the Bridge to Political Power

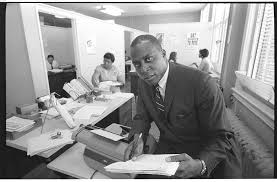

Programs don’t move history — people do. At the Southern Regional Council (SRC), two senior staff members exemplified how institutional leadership could translate analysis into action and research into results. Steve Suitts and Kenny Johnson were not only administrators; they were architects of strategy, voice, and reach.

- Steve Suitts, as Executive Director, consolidated SRC’s intellectual authority and public identity. With a background in legal analysis, education policy, and Southern political strategy, he transformed internal reports into press-ready narratives and donor-facing rationales. His later scholarship extended SRC’s influence into national debates on schooling, law, and civic inclusion.

- Kenny Johnson, Director of the Southern Labor Institute and later Deputy Director of SRC, bridged legislative professionalism with grassroots governance. His work connected SRC research to state-level policy, providing technical and policy support to elected officials and legislative caucuses. His reports were consumed by lawmakers seeking grounded, actionable insight.

Together, Suitts and Johnson formed the institutional core that made SRC’s recommendations credible, quotable, and implementable. When governors, donors, and presidential appointees looked to understand the Southern political landscape, it was often their voices — refined through SRC’s infrastructure — that shaped the response.

🔍 Steve Suitts: Architect of Evidentiary Strategy and Southern Political Infrastructure

As Executive Director of the Southern Regional Council (SRC) from the early 1980s through the mid-1990s, Steve Suitts led the Council through one of its most consequential eras — expanding its Voting Rights Programs, deepening its documentation standards, and positioning it as a strategic intermediary between grassroots movements and institutional power.

Suitts understood that civil rights enforcement required more than moral clarity — it demanded data, policy precision, and legal infrastructure. Under his leadership, SRC became a trusted source of evidentiary material for Voting Rights Act litigation, redistricting battles, and policy reform. He oversaw the production of Southern Changes and Voting Rights Review, ensuring that the Council’s publications served both as public education tools and as technical resources for litigators, elected officials, and organizers.

He also helped shape the Council’s funding strategy, maintaining relationships with foundations like Ford and Carnegie while protecting SRC’s mission integrity. His stewardship balanced institutional survival with movement relevance — a delicate tension that defined the Council’s role in the post-1965 South.

Suitts mentored a generation of staffers and field operatives, including Kenny Johnson, who served as Deputy Director during his tenure, Ellen Spears, whose editorial leadership shaped SRC’s public voice, and Selwyn Carter, who later directed the Voting Rights Programs and helped architect the Council’s redistricting strategy. Together, they built the connective tissue between registration drives, litigation support, and policy advocacy — translating grassroots momentum into structural change.

Beyond SRC, Suitts has remained a leading voice in Southern political analysis, education equity, and historical recovery. His scholarship and public commentary continue to inform debates on race, democracy, and institutional accountability.

As this exposé transitions into a digital archive, Suitts’s contributions will anchor the evidentiary foundation — guiding both historical reckoning and future organizing.

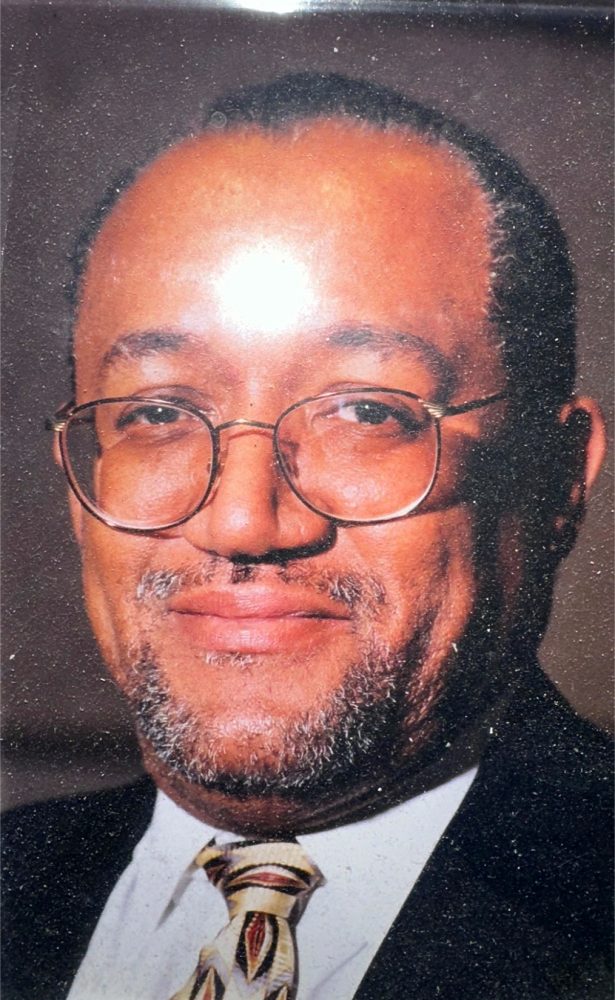

🔍 Kenny Johnson: Strategic Steward of Voting Rights, Labor Equity, and Legislative Support

From the early 1980s through the mid-1990s, Kenny Johnson served as Deputy Director of the Southern Regional Council (SRC) under Executive Director Steve Suitts, and as Director of the Southern Labor Institute, a special project housed within SRC. His leadership spanned voting rights enforcement, labor equity, and policy infrastructure — making him one of the most versatile and impactful strategists of the era.

As Deputy Director, Johnson helped coordinate field operations, litigation support, and coalition outreach. He was instrumental in translating SRC’s policy priorities into actionable programs across the South, ensuring that registration gains and redistricting victories were matched by sustained community engagement and legal reinforcement.

Through the Southern Labor Institute, Johnson reframed economic justice as a civil rights imperative. He authored influential reports like The Climate for Workers, published in Southern Exposure, which challenged traditional business climate metrics and offered a worker-centered analysis of Southern economies. These reports were not just academic — they were consumed by elected officials and legislative caucuses, providing technical and policy support for lawmakers seeking to address wage stagnation, working poverty, and regional disparities.

Johnson’s dual role positioned him as a bridge between grassroots data and institutional policy. His work informed debates on labor reform, voting rights enforcement, and coalition strategy — often serving as a quiet but essential resource for Southern legislators navigating complex political terrain.

When Suitts departed SRC in the mid-1990s, Johnson stepped in as Interim Executive Director, guiding the organization through a period of transition while the Board conducted an external search. His stewardship preserved SRC’s credibility and mission continuity during a critical juncture.

Johnson’s legacy is infrastructural and intellectual. He helped build the connective tissue between civil rights litigation, voter registration, labor advocacy, and legislative strategy. As this exposé transitions into a digital archive, Johnson’s contributions will anchor both the historical record and the advisory vision for future movement infrastructure.

📝 Ellen Spears: Editorial Architect of SRC’s Public Voice

For years, Ellen Spears served as a lead editor and contributor to the Council’s publications, including Southern Changes and Voting Rights Review. Her editorial stewardship helped define the Council’s intellectual tone — blending investigative rigor, cultural analysis, and movement documentation into a coherent public voice.

Spears curated and authored pieces that elevated grassroots narratives, challenged institutional racism, and documented the lived realities of Southern communities. Her work included interviews, policy critiques, and cultural reportage, often spotlighting underrepresented voices and overlooked histories. Through her editorial lens, SRC’s publications became more than internal reports — they became tools for public education, legal strategy, and coalition-building.

After her tenure at the Council, Spears pursued advanced scholarship at Emory University, where she earned her MA and PhD and later taught in the fields of environmental history, social movements, and Southern studies. Her academic work — including Baptized in PCBs: Race, Pollution, and Justice in an All-American Town — extended the SRC’s legacy into environmental justice and public health advocacy.

Spears exemplifies the bridge between movement journalism and scholarly infrastructure. Her editorial leadership helped SRC’s publications become quotable, teachable, and legally actionable — and her later scholarship ensured that the Council’s ethos lived on in classrooms, courtrooms, and community organizing.

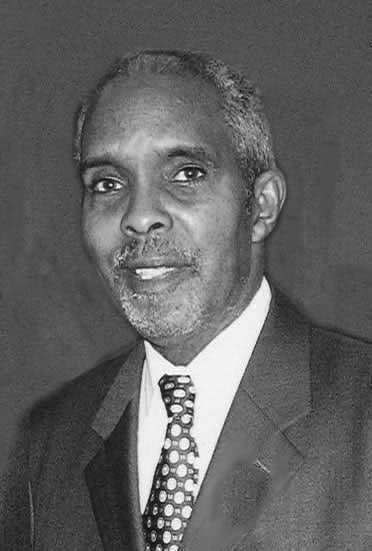

🧭 Selwyn Carter: Architect of Redistricting Strategy and Movement Infrastructure

Selwyn Carter joined the Southern Regional Council in the early 1990s, bringing with him a rare blend of grassroots mobilization experience, technical mastery, and strategic vision. Recruited from New York City after leading Countdown 88 and Countdown 89 — two landmark voter mobilization and redistricting campaigns — Carter assumed leadership of SRC’s Voting Rights Programs during a pivotal moment in Southern political history.

His work extended beyond technical mapping into high-stakes legislative negotiation. In Montgomery, Alabama, Carter built deep relationships with members of the Legislative Black Caucus, working closely with Caucus leader George Purdue to draft and build support for the Purdue Plan — a redistricting proposal that successfully advanced through the state’s Constitution and Elections Committee.

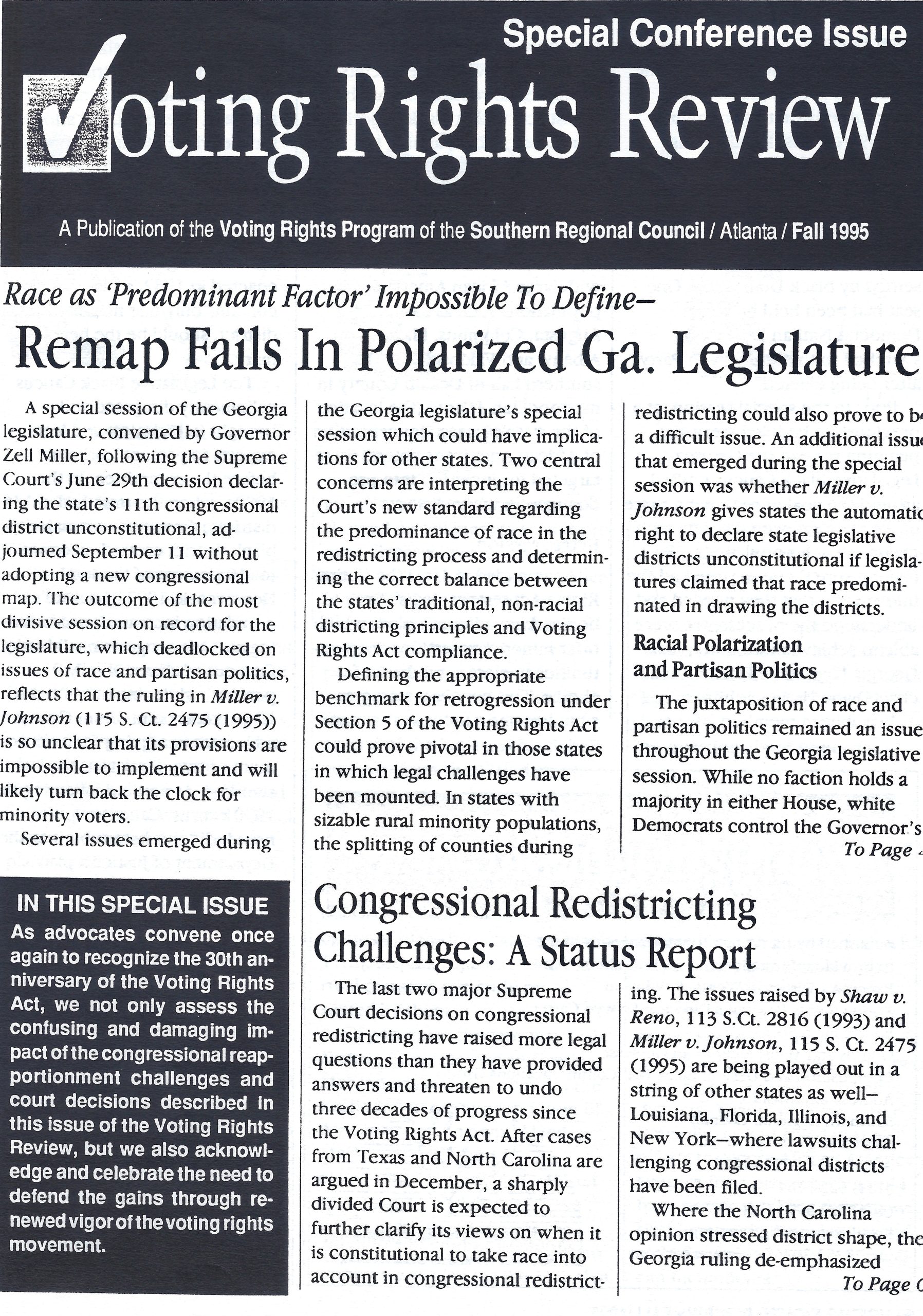

In SRC’s home base of Atlanta, Carter collaborated with the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus to design a congressional redistricting plan that created three majority-Black districts. The plan anchored one district in Fulton County (Atlanta), a second in DeKalb County stretching east through the Black Belt to Savannah, and a third spanning the central and southwestern regions of the state. When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Georgia’s 11th Congressional District in Miller v. Johnson (1995), Carter camped out at the Georgia Capitol, serving as a critical liaison between the Caucus and political power brokers.

His technical assistance and strategic guidance helped the Caucus navigate a volatile redistricting session, which he later analyzed in the Fall 1995 special issue of Voting Rights Review:

“The Georgia Special session on redistricting demonstrated that as a result of the Supreme Court’s decisions, state legislators are faced with a dilemma: if they draw majority Black districts, they face lawsuits under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment; if they fail to do so, they face challenges by minorities under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act and lawsuits under Section 2… this conflict will increasingly be resolved at the expense of African American and other minority voters.”

His warning was echoed in national media. In a July 1995 New York Times article, Carter cautioned that Georgia’s response could “send a signal to other states to curb any increases in the number of majority Black districts and to challenge some of the ones that have been drawn in the last 5 to 10 years” (source).

Carter later provided expert witness testimony in federal court in Augusta, helping to document the racial and political dynamics at play. His legacy at SRC is both infrastructural and visionary — translating legal victories into durable tools, trainings, and district maps that empowered a new generation of Black elected officials. As Editor-in-Chief of BlackPolitics.org, he continues to digitize and extend that legacy, building platforms that connect historical records to actionable advocacy.

Origins and Institutional Method: How the Council Built a Platform for Change

The Southern Regional Council’s organizational DNA combined research, communications, philanthropic intermediation, and program administration. That combination allowed it to function simultaneously as a funder intermediary, a policy lab, and a narrative center that translated movement metrics into the language of law, philanthropy, and electoral strategy. Its publications — the long‑running Southern Changes and the more targeted Voting Rights Review among them — were not mere propaganda; they were working instruments that summarized field data, framed legal arguments, publicized suppression tactics, and suggested institutional remedies. Because the Council carried credibility with both private foundations and policy audiences, its reporting often determined which organizations received sustained funding and which legal or legislative strategies were prioritized.

Two institutional design choices were especially consequential. First, the organization embraced a decentralized funding model for voter work: rather than directly running every registration drive, SRC, through mechanisms like the VEP, channeled foundation funds to local Black‑led organizations that had trusted grassroots reach. Second, it paired that funding with rigorous reporting and standards for accountability, which created a professionalized ecosystem for voter contact and electoral preparation that eased the transition from registration to candidate recruitment and successful campaigns.

These structural features — intermediary capital plus administrative standards plus public documentation — made SRC uniquely capable of influencing both the mechanics of voter mobilization and the structural reforms (e.g., district‑based representation) that turned turnout into officeholding.

1960s – Voter Education Project (VEP): Scale, Strategy, and Key Players

VEP was the clearest expression of SRC’s strategy to convert philanthropic resources into lasting civic capacity. Launched in the early 1960s, its operating logic was simple but powerful: provide reliable, scalable funding to local organizations for voter education and registration, while requiring standardized reporting on outcomes. That combination produced three practical effects that reverberated for decades.

- Rapid expansion of registered Black voters. By directing funds to targeted local drives, the project helped register very large numbers of Black citizens in the Deep South at a crucial historical moment. Those registration gains created the numerical base necessary for organized electoral challenges to entrenched white‑dominated institutions.

- Professionalization of voter work. The obligation to track registration numbers, organize data, and report outcomes forced local groups to adopt administrative practices that translated directly into campaign capacity: voter rolls, precinct captains, canvass lists, turnout planning, and basic campaign finance and volunteer management.

- Pipeline development for leaders. VEP did not only increase registrations; it also created a training ground and visibility platform for a generation of Black organizers and candidates. The skills and community credibility cultivated through sustained registration campaigns produced the human infrastructure for candidate recruitment and successful runs for school boards, city councils, state legislatures, and Congress.

Julian Bond and the Voter Education Project

Key figures associated with VEP extend across organizational lines. Movement leaders and public intellectuals offered moral authority and media visibility while local directors and field organizers executed day‑to‑day registration work. Julian Bond is often cited among the higher‑profile public figures who helped elevate the voter education cause and who worked across networks that intersected with SRC’s efforts; similarly, an array of SNCC, NAACP, and local civic leaders served as primary implementers in dozens of counties.

VEP’s reach was not unopposed. Segregationist machines, local registrars, and sometimes violent private actors resisted registration drives. In many places, registration gains were contested in court or attacked extra‑legally. SRC’s publication apparatus and later Voting Rights Programs offered both publicity for those challenges and the empirical documentation/technical support lawyers needed to press for remedies.

Selwyn Carter

On the C-SPAN Networks:

Southern Regional Council Voting Rights Programs Director, Selwyn Carter, at a Congressional News Conference. December 9, 1996 – in front of the US Supreme Court after listening to the oral arguments in the Georgia congressional redistricting case with Rep. Cynthia McKinney (D-GA), attorneys (including key SRC litigation partner, Laughlin McDonald, Director of the Southern Legal Office of the ACLU), and supporters.

Voting Rights Programs: From Registration to Institutional Defense

The passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 altered the legal terrain in profound ways, but victories on paper required constant enforcement and sustained local political work. At every juncture, the forces of resistance, Jim Crow, and reaction in the South adapted to block African American political empowerment. After civil rights activists registered hundreds of thousands of new Black voters across Southern states, new barriers were erected to ensure those voters couldn’t cast ballots or elect candidates. These included at-large voting systems, gerrymandering, and administrative tactics designed to dilute Black voting strength — all of which persisted well after 1965.

SRC’s Voting Rights Programs marked a strategic pivot from pure registration funding toward a broader, integrated approach: combining field support, legal collaboration, legislative education, technical expertise — including the use of GIS systems to model and advocate for majority-Black districts — and investigative reporting to protect and expand gains.

“At every juncture, the forces of resistance, Jim Crow, and reaction in the South adapted to block African American political empowerment. After hundreds of thousands of Black voters were registered, new barriers — like at-large voting and vote dilution — were erected to prevent them from electing representatives.”

Learn more about vote dilution tactics

Supporting Sources

- History.com: How Jim Crow Laws Suppressed Black Voting

- Election Law Blog: At-Large Voting and Vote Dilution

- GovFacts: Legal Threats to the Voting Rights Act

Voting Rights Programs performed several essential functions:

Monitoring and documenting suppression. The Council produced reports and newsletters that traced where suppression persisted, whether in the form of discriminatory registration practices, at‑large electoral structures that diluted Black votes, or subtler administrative hurdles. These efforts increasingly incorporated demographic analysis and spatial data, allowing it to pinpoint patterns of exclusion and model alternative district configurations.

Supporting litigation partners. SRC’s empirical research and local reporting provided source material for litigation, helping lawyers demonstrate patterns of discrimination, the impact of at‑large systems, and the need for districting remedies that complied with the Voting Rights Act’s protections. This included GIS-based map drawing, population modeling, and expert testimony — tools that proved essential in courtrooms and redistricting committee hearings across the South.

Translating legal wins into political infrastructure. Where litigation created judicially ordered changes, the Council helped local organizations transition from litigation victories to sustained electoral competitiveness, ensuring that newly created majority‑Black districts produced both turnout and representative candidates. SRC’s technical support extended to training legislative Black caucuses and grassroots leaders on how to interpret maps, mobilize voters, and defend district integrity.

Legislative engagement and model policies. SRC did not only support litigation; through the Southern Legislative Institute and targeted briefings, it helped shape the legislative playbook that would institutionalize reforms like single‑member districts, combining litigation pressure with legislative reform. Its technical capacity enabled data-driven policy proposals, equipping lawmakers with the tools to challenge gerrymandering and codify equitable representation.

By the early 1990s, the Southern Regional Council’s Voting Rights Programs had entered a new phase — not winding down, but building on decades of hard-won progress and two transformative legal milestones. The redistricting cycle following the 1990 census was the first to take place after the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act, which clarified that Section 2 prohibited voting practices that had a discriminatory effect, not just intent. This shift made it legally possible — and strategically necessary — to draw districts where African Americans could elect candidates of their choice, even in the absence of overt discrimination.

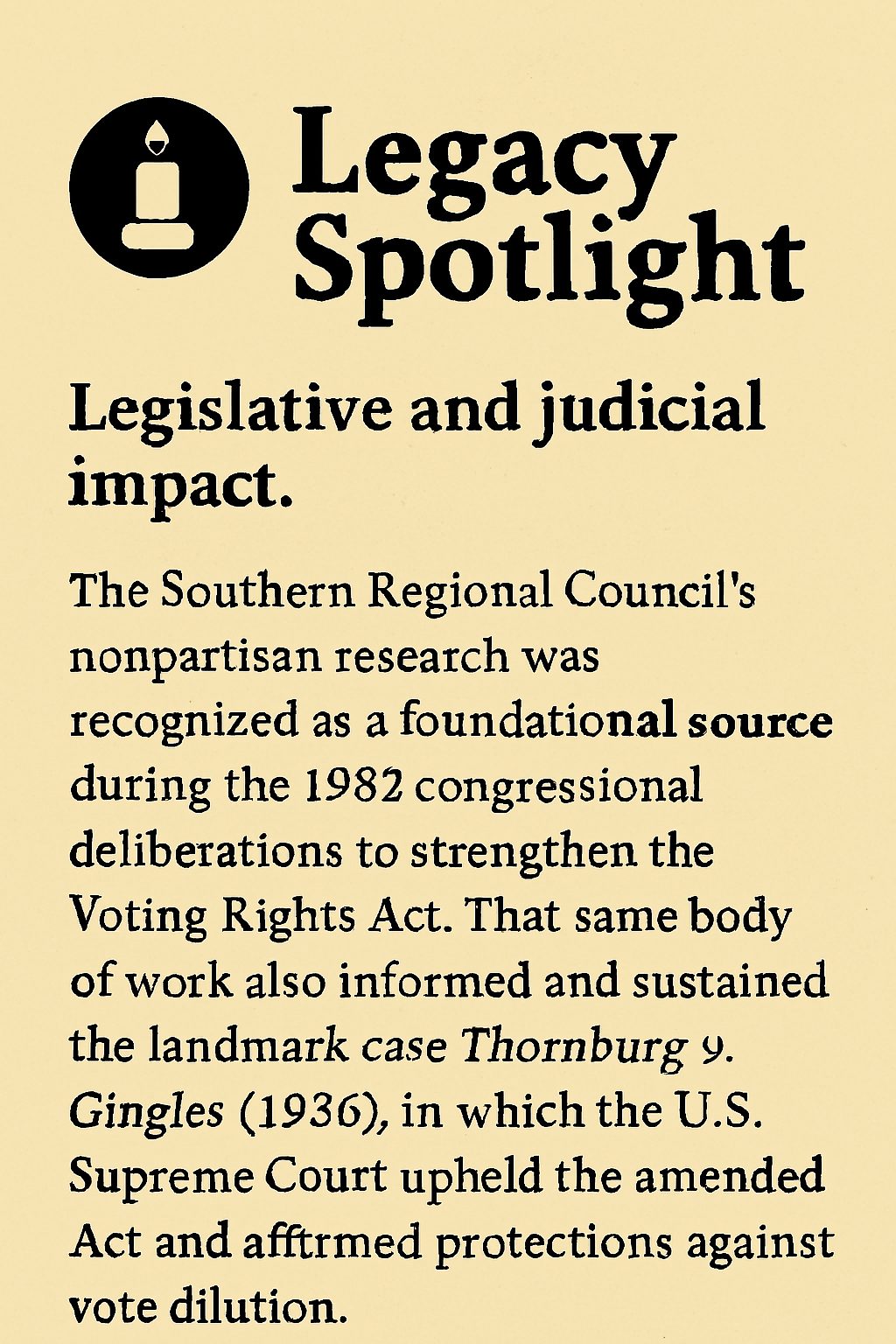

That legal foundation was sharpened by the 1986 Supreme Court decision in Thornburg v. Gingles, which established a three-pronged test for proving vote dilution under Section 2. The ruling emphasized the importance of racially polarized voting and the need for geographically compact districts — criteria that could be demonstrated through rigorous demographic analysis and mapping.

Legislative and judicial impact. The Southern Regional Council’s nonpartisan research was recognized as a foundational source during the 1982 congressional deliberations to strengthen the Voting Rights Act. That same body of work also informed and sustained the landmark case Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the amended Act and affirmed protections against vote dilution.

During the pivotal period of the early 1990s, the Voting Rights Programs were led by the same individual who now serves as Editor-in-Chief of BlackPolitics.org, ensuring continuity between past advocacy and present-day documentation. Under this leadership of the Voting Rights Programs, SRC deployed GIS-based redistricting tools, trained technical experts from communities of color nationwide, and supported litigation and legislative reform across eleven Southern states. The program’s work helped local leaders leverage new legal openings to win elections, defend district integrity, and build sustainable political infrastructure rooted in the Voting Rights Act’s evolving protections.

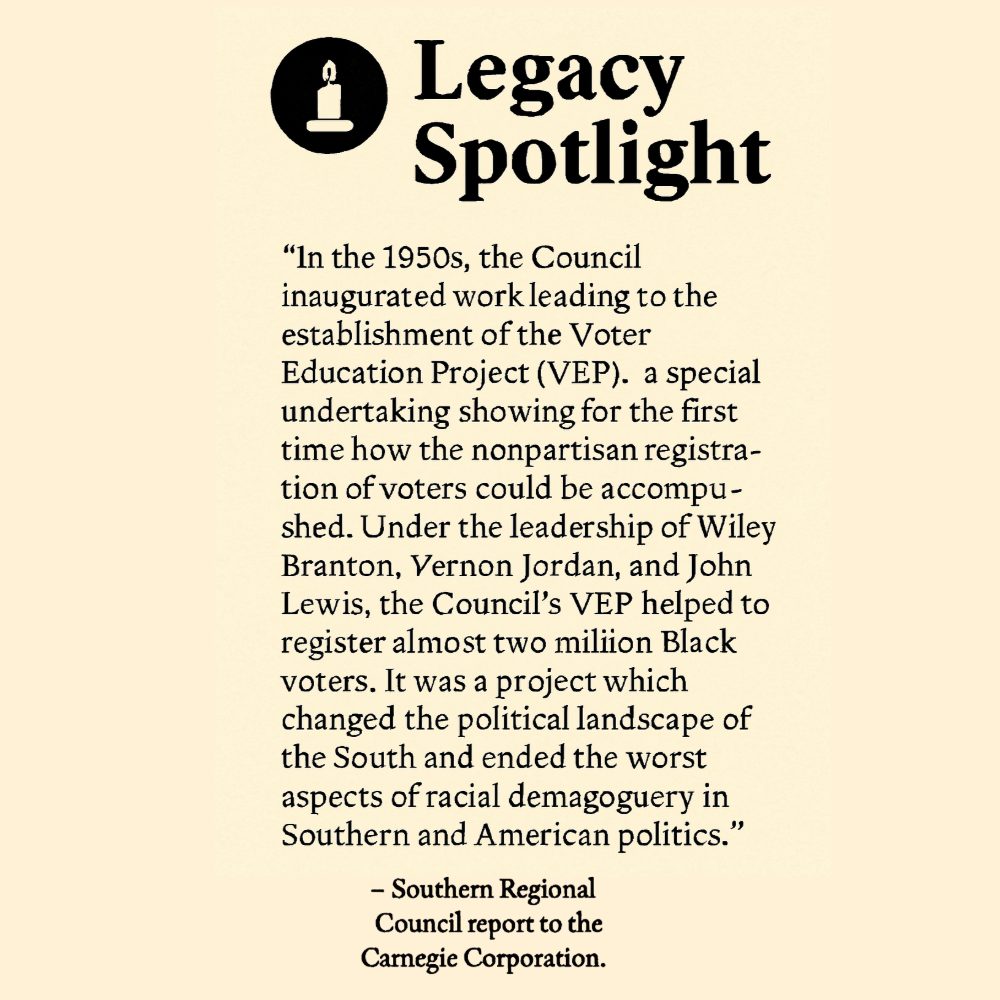

🏛️ Legacy Spotlight: The Voter Education Project (VEP)

“In the 1950s, the Council inaugurated work leading to the establishment of the Voter Education Project (VEP), a special undertaking showing for the first time how the nonpartisan registration of voters could be accomplished. Under the leadership of Wiley Branton, Vernon Jordan, and John Lewis, the Council’s VEP helped to register almost two million Black voters. It was a project which changed the political landscape of the South and ended the worst aspects of racial demagoguery in Southern and American politics.” — Southern Regional Council report to the Carnegie Corporation

Notably, both Vernon Jordan and John Lewis went on to become national leaders — Jordan as a presidential advisor and civil rights strategist, and Lewis as a long-serving Congressman and moral voice of the movement. Their early work with VEP helped shape the infrastructure of Black political power for generations.

Timeline of Voting Rights Milestones and Black Representation

| Year | Milestone | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Voting Rights Act Amendments | Strengthened Section 2 to prohibit voting practices with discriminatory effects, enabling legal challenges to vote dilution and paving the way for majority-Black districts. |

| 1986 | Thornburg v. Gingles (SCOTUS) | Established a three-part test for proving vote dilution: racially polarized voting, compactness, and historical discrimination. Validated the use of race-conscious redistricting as a remedy for vote dilution under Section 2. |

| 1990–1995 | Post-Census Redistricting Gains | First redistricting cycle under new legal standards. GIS mapping and litigation led to a surge in majority-Black districts and a dramatic increase in Black elected officials across the South. |

| 2025 | Threat: Louisiana v. Callais | Supreme Court signals potential rollback of Gingles protections. Justice Kavanaugh’s questioning suggests a shift that could dismantle decades of legal precedent and hard-won gains. |

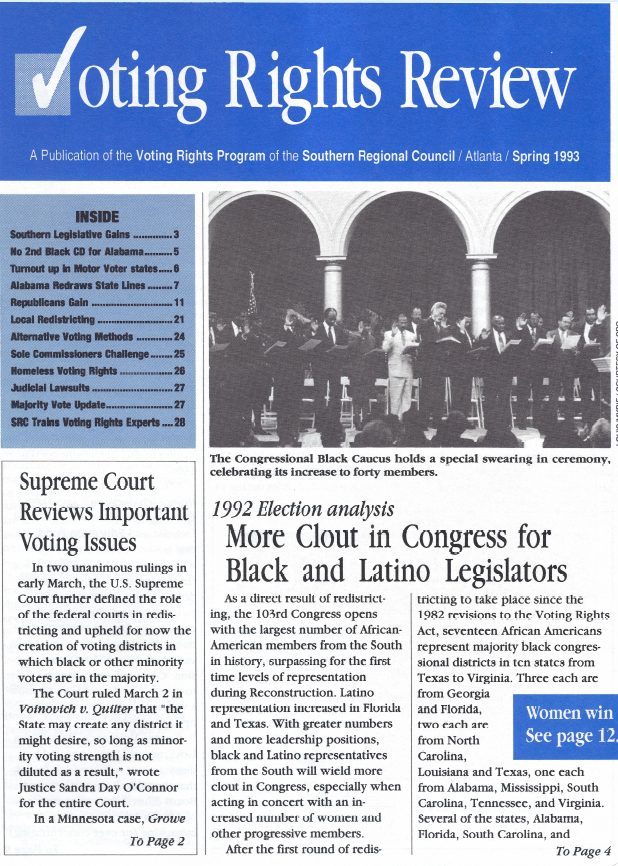

As a direct result of redistricting, the 103rd Congress opens with the largest number of African American members from the South in history, surpassing for the first time the levels of representation during Reconstruction.

Voting Rights Review, a Publication of the Voting Rights programs of the Southern Regional Council – Spring 1993 – Front page

Sidebar: Redistricting and the Rise of Southern Black Representation

📊 Sidebar: Redistricting and the Rise of Southern Black Representation

- In 1990, prior to the census, only five Southern states had elected African Americans to Congress.

- By 1992, after applying the amended Voting Rights Act to new census data, the number of Congressional Black Caucus members from the South surged from 5 to 17 — a direct result of race-conscious redistricting under Section 2 and the Thornburg v. Gingles framework.

This dramatic expansion marked the first time since Reconstruction that Southern Black representation in Congress reached double digits — a milestone made possible by legal remedies designed to counter vote dilution and empower communities of color.

Publications as Policy Tools: Southern Changes and Voting Rights Review

Publications were a core instrument of SRC’s influence. Southern Changes offered longer essays and broad analysis of Southern social trends, while Voting Rights Review functioned as a targeted vehicle for documenting voting irregularities, reporting on litigation, and providing practical guidance.

These periodicals did more than inform; they shaped philanthropy, litigation strategy, and legislative debate in at least three ways:

- Agenda‑setting: By documenting patterns of exclusion, SRC publications focused national attention on specific jurisdictions and practices that merited intervention.

- Evidence production: Rigorous reporting — often including county‑level registration data, precinct studies, and analyses of at‑large systems — created evidentiary foundations that lawyers and advocates used in briefs and hearings.

- Knowledge diffusion: The journals circulated methodologies, sample ordinances, and case studies, enabling activists in one locality to replicate successful approaches demonstrated elsewhere.

The cumulative effect of sustained publication was to lower the transaction costs of reform: SRC told funders where interventions were needed, supplied litigators with empirical material, and gave local activists replicable strategies for converting registration gains into effective representation.

The lead article of the Winter 1992 edition off the Voting Rights Review ends up with the following statement, “As redistricting battles unfold in Southern legislatures, the creation of ten to 15 new majority black and Hispanic congressional districts now appear certain.”

Creating Majority‑Black Districts: Litigation, Local Partners, and SRC’s Role

One of the most tangible political outcomes attributable in part to SRC’s ecosystem was the creation of majority‑Black districts where none had existed. The process typically followed a recognizable sequence in which registration gains exposed representational distortions, litigation or political pressure demanded remedies, and institutional intermediaries (including the Council) helped operationalize those remedies.

Typical sequence:

- Registration gains reveal dilution. As VEP‑supported drives increased Black rolls, public data began to show a mismatch between population and representation, especially in jurisdictions that used at‑large elections.

- Documentation and publicity. SRC’s monitoring publications documented the mismatch and publicized successes and failures, creating pressure on local governments and giving litigators the public evidence to frame legal claims under the Voting Rights Act.

- Litigation or legislative remedy. Civil‑rights lawyers, sometimes in collaboration with local partners, filed suits arguing that at‑large systems diluted Black votes and violated federal protections; alternatively, political pressure or state legislation compelled jurisdictions to adopt single‑member or majority‑Black districts.

- Implementation and community engagement. Following the redrawing of district boundaries, a variety of local partners collaborated to support candidate development and public policy education. These efforts helped ensure that newly created districts translated into meaningful representation for Black communities, strengthening civic participation and leadership across the South.

Examples and patterns (illustrative, based on the historical arc the Council documented and supported):

- Municipal and school board districts. Across Southern cities, at‑large systems for city council and school board seats were often replaced with single‑member districts. In many of those cases, SRC reporting and local VEP‑funded efforts documented both the numerical possibility of Black representation and the administrative obstacles that required judicial or legislative remedies.

- State legislative districts. As registration expanded and litigation or consent decrees forced redistricting, Black voters gained the ability to elect state legislators in newly created majority‑Black districts, contributing to the growth of state legislative Black caucuses.

- Congressional districts. The creation and defense of majority‑Black congressional districts — where demographic thresholds and compactness rules permitted — followed similar patterns. Increased registration and political consolidation made the legal and political argument for majority districts more persuasive, and SRC’s publications often accompanied and reinforced those efforts.

The critical point is the ecosystem: registration (VEP), documentation (SRC publications), litigation partners (national and local civil‑rights lawyers), and legislative or judicial remedies together created majority‑Black districts that produced a new class of elected Black officials.

Named Examples: Officials, Districts, and Pathways to Office

Tracing the careers of specific officials and the districts that produced them underscores SRC’s practical influence. The following examples are illustrative of a broader trend in which registration campaigns and subsequent district reforms enabled Black electoral emergence.

- Municipal leadership. In many Southern cities that once used at‑large systems, the shift to district elections enabled the election of Black council members and later Black mayors. Those municipal breakthroughs often predated or paralleled state legislative advances and were crucial first steps in building governing experience and public visibility.

- State legislators. Across the Deep South, the growth of majority‑Black legislative districts contributed to the formation and expansion of Black state legislative caucuses. Those caucuses became pipelines for national office and signaled a substantive shift in the policymaking profile of Southern legislatures.

- Congressional representation. The coalescence of majority‑Black congressional districts in some states required decades of registration work, litigation momentum, and political consolidation. Where those districts were created and sustained, Black members of Congress emerged who could translate local organizing priorities into federal policy.

Board Networks: SRC’s Political Incubator

SRC’s board and advisory relationships were not ceremonial. Board membership often functioned as a political hub that connected civic leaders, elected officials, and rising political talent. Board members provided SRC with access to state capitals, city halls, and national philanthropic networks while SRC, in turn, provided board members with research, narratives, and policy tools they used in office.

Key board figures and their political roles include (brief overviews — expand with archival mastheads and dated board lists):

Embed from Getty Images Embed from Getty Images Embed from Getty Images

- Shirley Franklin — Her municipal leadership in Atlanta and civic stature intersected with SRC’s municipal reform and urban policy concerns; SRC’s urban research helped frame reform agendas that Franklin later implemented as mayor.

- Jim Clyburn — As a long‑serving U.S. Representative and House leader, Clyburn’s networks intersected with SRC’s efforts to translate Southern political developments into national policy conversations.

- Bennie Thompson — His legislative work on voting and homeland security issues reflects the trajectory of SRC’s emphasis on both voter protection and broader governance challenges.

- Lottie Shackelford — As both a municipal official and longtime Democratic National Committee vice chair, Shackelford’s leadership on SRC’s board provided national party channels that amplified SRC’s priorities.

- Tony Harrison, executive director of the Electoral Participation Project, and other regional leaders — These board members often served as essential connectors between SRC’s research and the tactical decisions made at the state and local level.

The SRC board therefore operated as a talent pipeline, incubator, and confirmatory audience: board members could test strategies in SRC forums, mobilize funding, and then carry those strategies into governance settings.

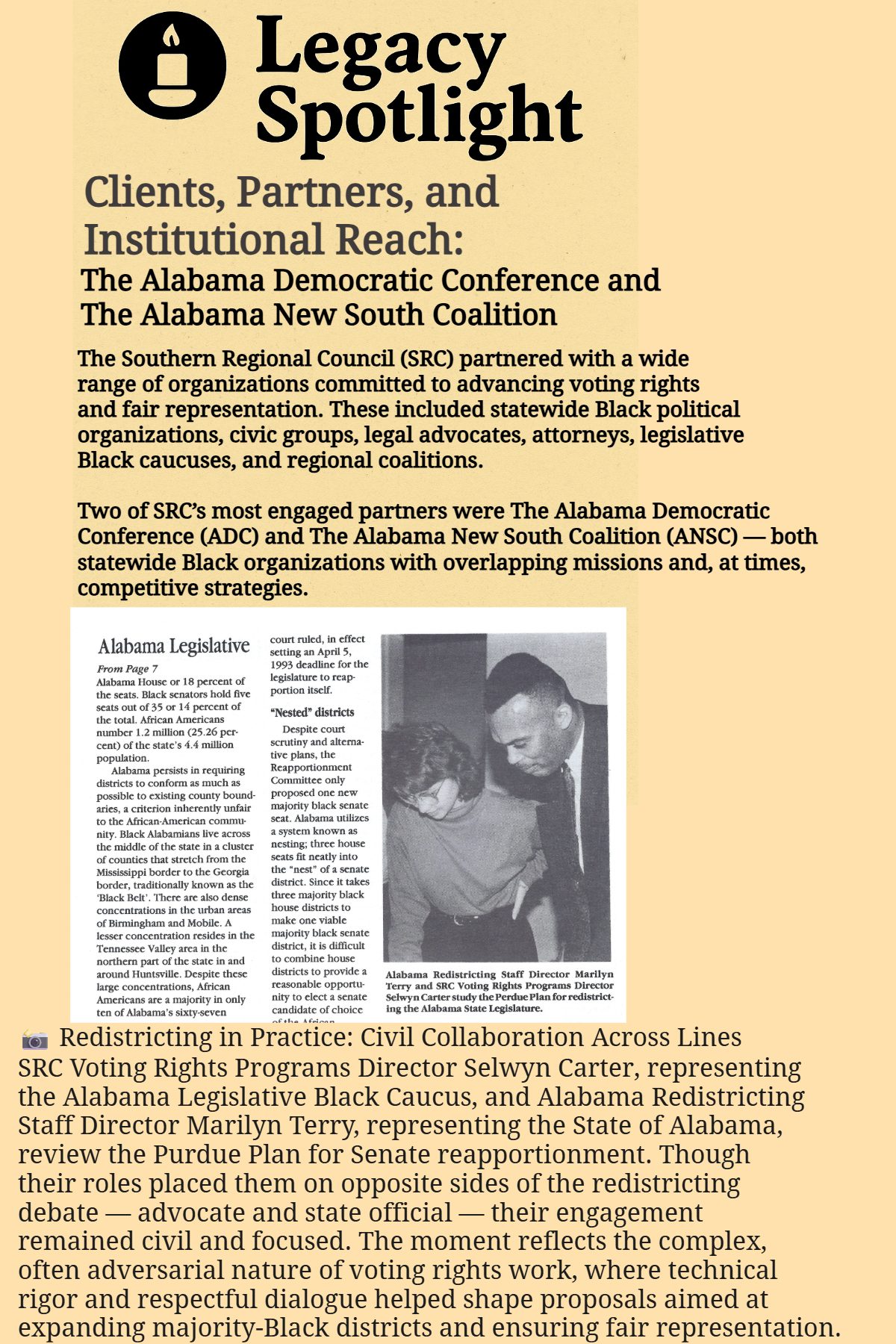

Clients, Partners, and Institutional Reach:

The Alabama Democratic Conference and The Alabama New South Coalition

The Southern Regional Council (SRC) partnered with a wide range of organizations committed to advancing voting rights and fair representation. These included statewide Black political organizations, civic groups, legal advocates, attorneys, legislative Black caucuses, and regional coalitions.

Two of SRC’s most engaged partners were The Alabama Democratic Conference (ADC) and The Alabama New South Coalition (ANSC) — both statewide Black organizations with overlapping missions and, at times, competitive strategies. SRC worked with each on voting-rights research, voter education, and redistricting support. ADC field staff, including figures such as Jerome Gray, regularly collaborated with SRC to translate technical research and funding into field operations.

SRC’s intermediary role allowed organizations like ADC and ANSC to scale their efforts with administrative and narrative support. Through its publications, SRC amplified local victories and documented persistent barriers, offering both technical validation and public visibility. These relationships exemplified how SRC’s work intersected with partisan Black political organizations while remaining institutionally distinct and nonpartisan.

A pivotal example appears in the Voting Rights Review (Spring 1993), which documents the Alabama House reapportionment committee’s rejection of a plan presented by Purdue. Instead, the committee adopted a “working plan” that added only three majority-Black seats. As the Review states:

“The Purdue Plan, by contrast, creates an additional nine majority Black seats… The Purdue Plan, drafted at the request of the Alabama Legislative Black Caucus by demographers from the Voting Rights Programs of the Southern Regional Council, also creates an additional two to three majority Black seats in the Alabama Senate.”

The same issue highlights coalition support behind the plan:

“Among the Black leaders endorsing the Purdue Plan is Carol Zippert, president of the Alabama New South Coalition, who spoke for the plan before the committee at its December 8, 1992 meeting.”

Institutional Tensions, Critiques, and Unresolved Questions

No institutional history is unvarnished. SRC’s intermediary model created productive leverage but also generated tensions and criticisms that are essential to an honest appraisal.

Strategic Fault Lines in SRC’s Voting Rights Infrastructure

Despite its technical sophistication and broad coalition reach, the Southern Regional Council’s Voting Rights Program (VEP) faced persistent critiques from activists, scholars, and partner organizations. These critiques centered on three interrelated tensions: philanthropic conditionality, moderation versus militancy, and interracial governance vs. Black-led strategy.

🏛️ Philanthropic Conditionality

Much of SRC’s operational capacity depended on foundation funding, particularly from the Ford Foundation, Field Foundation, Carnegie Corporation, and Rockefeller Foundation. Critics argued that VEP’s priorities were shaped less by grassroots urgency and more by donor risk appetites. Foundations often favored measurable, moderate interventions — such as precinct-level targeting and litigation support — over more confrontational or experimental activism.

“The shift from mass mobilization to technical assistance reflected a donor-driven preference for policy infrastructure over direct action.” — Southern Changes, Vol. 7, No. 3 (1985)

⚖️ Moderation vs. Militancy

SRC’s intermediary model brought bureaucratic rhythms and accountability demands that sometimes clashed with the guerrilla tactics favored by frontline organizers. In states like Mississippi and Alabama, SNCC veterans and local activists occasionally chafed at SRC’s pace and protocols, which they saw as limiting spontaneity and base-level energy.

“Some felt that SRC’s gatekeeping role constrained the very militancy that energized Black political life.” — Woodruff Library, SRC Collection, Box 14, Folder 3

🤝 ✊🏿 Interracial Governance vs. Black-Led Strategy

SRC’s interracial posture helped secure access to philanthropic and political arenas, but also generated mistrust among activists who sought independent Black control of strategy and resources. Board composition and strategic decision-making were sometimes perceived as diluted or misaligned with Black constituencies.

“The tension between interracial credibility and Black autonomy was never fully resolved.” — Avery Research Center, SRC Correspondence, 1991

References

- Southern Changes, Vol. 7, No. 3 (1985), “Voting Rights and the Southern Regional Council”

- Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center, Southern Regional Council Papers

- Avery Research Center, College of Charleston, Southern Regional Council Collection

- Carnegie Corporation and Rockefeller Foundation grant records, 1980s–1990s (available via foundation archives and grant reports)

Archival Insert: Strategic Fault Lines in SRC’s Voting Rights Infrastructure

These tensions do not negate SRC’s measurable contributions; they do complicate narratives that frame SRC as an idealized force for progress. A careful expose must acknowledge the tradeoffs implicit in SRC’s strategy: institutional durability can both produce sustained gains and limit tactical radicalism.

Jerry Wilson and Succession in the Voting Rights Programs

Jerry Wilson preceded my tenure as Director of the Voting Rights Programs. His stewardship in the years leading up to 1991 ensured programmatic continuity and preserved the institutional memory of VEP’s field lessons. Wilson’s leadership encompassed oversight of monitoring initiatives and coordination with litigation partners, stabilizing SRC’s engagement with local organizations during a period marked by shifting legal priorities and emerging administrative suppression tactics.

While his tenure included internal challenges reflective of SRC’s evolving governance landscape, Wilson’s coordination with legal partners preserved the program’s emphasis on evidence-based litigation support during a critical transition.

I was recruited from New York City in late 1990, having just concluded a successful term as Director of Countdown 88 and Countdown 89. Countdown was a major non-partisan citywide voter registration and Get Out the Vote initiative. It was followed by a redistricting campaign aimed at compelling the New York City Council to adopt a plan that provided fair and effective representation for racial and language minorities.

The timing was pivotal. The 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act and the 1986 Thornburg v. Gingles ruling had established new standards for minority vote dilution and district design. As the 1990 census approached, these legal precedents set the stage for aggressive redistricting and enforcement strategies. My recruitment into SRC’s Voting Rights Programs aligned with this moment of opportunity. I assumed responsibility for directing all phases of work to promote fairness in political representation across the American South — blending litigation support, technical training, and coalition engagement into a unified strategy.

🔚 Conclusion and Next Steps

The SRC’s influence on the trajectory of Black political empowerment in the South is both structural and human. Structurally, the Council’s intermediary model — VEP’s funding pipelines, the Voting Rights Programs’ monitoring and litigation support, and the publications’ evidence production — created the conditions that allowed registration gains to translate into elected office. Humanly, the board networks, staffers, and affiliated local leaders cultivated a generation of Black political actors who used those new institutions to expand representation and policy power.

Yet this legacy is not without contradiction. The SRC’s cautious posture, shaped by philanthropic constraints and institutional survival, often limited its tactical radicalism. Its contributions must be understood not as pure triumph, but as negotiated progress — forged in the tension between grassroots urgency and intermediary restraint.

This exposé is part of a broader effort to recover and digitize the infrastructure of Black political strategy before the internet. By documenting the field lessons, governance debates, and coalition dynamics that shaped the Voting Rights Programs, we begin to build a usable history — one that students, researchers, and emerging leaders can discover, quote, and extend.

The next phase will turn to Countdown 88 and Countdown 89, where mass mobilization and direct action in New York City offered a northern counterpart to SRC’s southern strategy. Together, these records form a living archive — not just of what was, but of what remains possible.

October 17, 2025