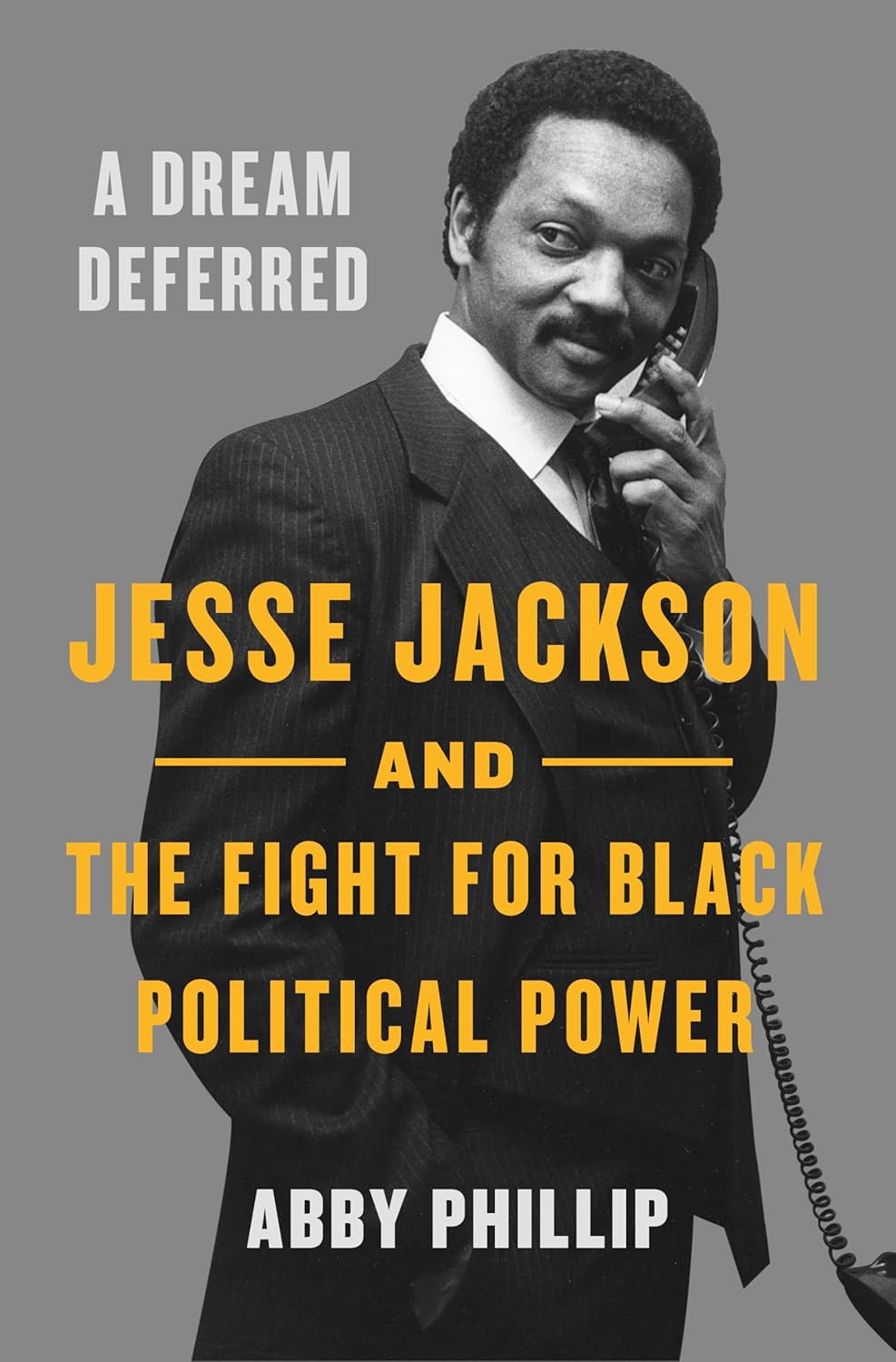

🌈 Jesse Jackson: Operation Breadbasket to Rainbow Push

Jesse Jackson legacy as civil rights leader, presidential candidate, and architect of Black political power. Complete biography, accomplishments, and lasting impact on American democracy. Jesse Jackson has done more to create combined Black political power and Black economic power than most African American leaders. Jackson’s political journey is one of audacity, coalition-building, strategic disruption, and economic accountability. From the pulpit to the pavement, Jackson transformed the landscape of Black political engagement—not by asking permission, but by expanding the lane.

Born in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1941, Jackson’s early life was shaped by segregation and resistance. He attended North Carolina A&T, where he became a student activist and protégé of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Through Operation Breadbasket, Jackson helped organize economic boycotts and job campaigns that linked civil rights to economic justice.

In 1971, Jackson founded Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity), a Chicago-based organization that fused faith, business accountability, and Black empowerment. PUSH became a national platform for Jackson’s vision: a multiracial, working-class coalition that could challenge entrenched power.

From Greenville to the National Stage: The Making of a Movement Leader

Jesse Louis Jackson was born on October 8, 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, to Helen Burns, a 16-year-old high school student, and her married neighbor, Noah Louis Robinson. Jackson was adopted at age two by his mother’s husband, Charles Henry Jackson, a post office maintenance worker who gave him his surname. Growing up in the segregated South, Jackson experienced firsthand the indignities of Jim Crow—an experience that would fuel his lifelong commitment to civil rights and economic justice.

Jackson’s early life was marked by both hardship and determination. He excelled in academics and athletics at Sterling High School in Greenville, earning a football scholarship to the University of Illinois. However, after being told he could not play quarterback because of his race, Jackson transferred to North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black college in Greensboro, where he could pursue both his athletic and academic ambitions without racial barriers.

At North Carolina A&T, Jackson found his calling. He became student body president and active in the civil rights movement, participating in sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro. It was during this period that Jackson met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who would become his mentor and the figure who would shape Jackson’s approach to activism—combining moral suasion, direct action, and coalition-building.

In 1964, Jackson moved to Chicago to attend the Chicago Theological Seminary. While in seminary, he worked with King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), eventually becoming the national director of Operation Breadbasket, SCLC’s economic justice program. Jackson used economic boycotts and negotiations with major corporations to create jobs and business opportunities for Black communities in Chicago and beyond.

When King was assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968, Jackson was there. The trauma of losing his mentor—combined with internal tensions within SCLC about succession and direction—would lead Jackson to chart his own path. In 1971, he founded Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity), establishing himself as an independent force in Black politics and civil rights advocacy.

Jackson married Jacqueline Lavinia Brown in 1962, and together they raised five children: Santita, Jesse Jr., Jonathan, Yusef, and Jacqueline Jr. Two of his son, Jesse Jackson Jr., and presently, Jonathan Jackson, would go on to serve in Congress, extending the family’s political legacy. Throughout his public life, Jackson’s family remained central to his identity, with Jacqueline often standing beside him through triumphs and controversies.

Major Milestones & Achievements: A Life of Firsts

Jesse Jackson’s career is marked by a series of groundbreaking achievements that expanded what was possible for Black political leaders in America:

1960s: The Civil Rights Foot Soldier

- 1963-1965: Active in Greensboro sit-in movement and civil rights demonstrations

- 1966: Ordained as a Baptist minister

- 1967: Appointed National Director of Operation Breadbasket by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

- 1968: Present at King’s assassination in Memphis; organized Chicago memorial service

1970s: Building Independent Black Economic Power

- 1971: Founded Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) in Chicago

- 1975: Launched PUSH-Excel program to promote educational excellence and economic opportunity for Black youth

- 1979: Led successful negotiations with major corporations (Coca-Cola, Anheuser-Busch, Burger King) for Black employment and business contracts

1980s: Presidential Campaigns and Political Revolution

- 1983: Successfully negotiated release of U.S. Navy pilot Lt. Robert Goodman from Syria

- 1984: First major Black presidential campaign; won 3.5 million votes and five primaries; registered over 2 million new voters

- 1984: Delivered historic “Common Ground” speech at Democratic National Convention

- 1986: Helped Democrats recapture Senate through voter mobilization efforts

- 1988: Won 7 million votes and 11 contests; most successful Black presidential campaign in U.S. history at the time

- 1988: Won New York City Democratic primary—unprecedented victory that demonstrated coalition power

1990s: International Diplomacy and Continued Activism

- 1990: Successfully negotiated release of hundreds of foreign nationals held hostage in Kuwait and Iraq

- 1991: Elected “shadow senator” for Washington, D.C., advocating for D.C. statehood

- 1993: Advocacy helped pass National Voter Registration Act (Motor Voter Law)

- 1996: Launched Wall Street Project to increase minority participation in corporate America and financial markets

- 1997: Founded Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, merging Operation PUSH with National Rainbow Coalition

- 1999: Negotiated release of three U.S. soldiers held in Yugoslavia during Kosovo War

2000s-2020s: Elder Statesman and Moral Voice

- 2000: Awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton

- 2008: Supported Barack Obama’s historic presidential campaign

- 2013: Arrested during protests for comprehensive immigration reform

- 2017: Diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease; continues advocacy work despite illness

- 2020: Endorsed Bernie Sanders for president; continued championing progressive causes

Awards and Honors

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (2000)

- NAACP Spingarn Medal (1989)

- Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize (2002)

- Multiple honorary doctorate degrees from institutions worldwide

- Named one of the “100 Most Influential Black Americans” by Ebony magazine for decades

Jesse Jackson 1984 Presidential Campaign

That vision crystallized in 1984, when Jackson launched his first presidential campaign. Though dismissed by many as symbolic, Jackson’s run was anything but. He won over 3 million votes, carried five states, and brought new voices into the Democratic Party. His campaign emphasized voter registration, anti-apartheid activism, and economic equity—issues that had long been sidelined.

Bill Lucy and the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU) were instrumental in this effort. Lucy helped mobilize labor support, build infrastructure, and connect Jackson’s campaign to working-class Black voters. Together, they modeled a new kind of political power—one rooted in movement, not machine.

Jesse Jackson 1988 Presidential Campaign

Jackson ran again in 1988, winning over 7 million votes and 11 contests. His campaign was the most successful presidential bid by a Black candidate in U.S. history at the time. He helped elect David Dinkins as New York’s first Black mayor, stood with Nelson Mandela in Brooklyn, and pushed the Democratic Party to adopt more inclusive policies.

Across the country, Jesse Jackson’s 1988 campaign didn’t just win votes—it built infrastructure. In cities like New York, Chicago, Atlanta, and Cleveland, Jackson’s mobilization of Black voters helped sweep local candidates into office. His campaign seeded the ground for David Dinkins in NYC, Carol Moseley Braun in Illinois, and Michael R. White in Ohio. In the Deep South, Jackson’s record-breaking Black turnout helped elect Black legislators in states like Alabama and Georgia. These victories weren’t incidental—they were the fruit of Jackson’s strategic investment in voter registration, coalition-building, and grassroots empowerment.

Long before the rise of Donna Brazile and Minyon Moore, Jesse Jackson’s influence inside the Democratic Party was already reshaping who could lead it. In the wake of his 1984 and 1988 campaigns—after millions of new Black voters had been registered and a multiracial delegate base had been organized—Jackson and his allies pressed the party to reflect that new reality. Ron Brown’s selection in 1989 as the first Black chair of the Democratic National Committee was the clearest early institutional expression of that pressure: a breakthrough made possible by the electorate Jackson helped build and the leverage his campaigns created inside the party.

🌟 The Next Generation: Jackson’s Political Apprentices and the DNC Connection

Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns became training grounds for a new generation of Black political operatives, strategists, and policy thinkers who would go on to transform the Democratic Party from the inside. Among the most notable were Minyon Moore and Donna Brazile, two women whose early work with Jackson’s national operations prepared them for major roles in the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and successive presidential campaigns.

Minyon Moore, who served as Jackson’s field director and later became one of the highest-ranking Black women in Democratic politics, refined her organizing skills within the crucible of the Rainbow Coalition. Her work in voter mobilization, delegate outreach, and grassroots communications directly informed the field strategies of Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, where she later played a senior role in political affairs. Moore would go on to become a key figure in the DNC and co-chair of the 2024 Democratic National Convention, carrying forward Jackson’s vision of grassroots empowerment and inclusion.

Donna Brazile, who also came of age within the Jackson movement, became one of the most visible Democratic strategists of her generation. Her expertise in voter mobilization, honed during Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 campaigns, shaped her leadership during Al Gore’s 2000 presidential campaign and her historic tenure as interim DNC Chair. Brazile’s work continued Jackson’s legacy of centering economic justice and racial equity within Democratic politics.

Together, Moore and Brazile embodied the institutionalization of Jackson’s ideals — that the Democratic Party’s base must reflect the diversity and strength of the American electorate. Through their work, the principles of Rainbow PUSH — inclusion, accountability, and coalition — became part of the Democratic Party’s DNA.

White House Archives — Minyon Moore • CNN — Donna Brazile

🗳️ The Jackson Coalition and the Rise of Southern Black Political Power

The ripple effects of Jackson’s campaigns extended far beyond the national stage. His Rainbow Coalition — rooted in churches, labor unions, student groups, and civic networks — energized Black political participation across the South like never before. In states such as South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, Jackson’s organizing operations built the foundation for a generation of Black elected officials and empowered local political infrastructures.

By the early 1990s, the political infrastructure seeded by Jackson was bearing fruit. Leaders such as Maxine Waters, who worked closely with Jackson’s movement in California before entering Congress, helped connect grassroots activism to federal power. In the South, John Lewis, Cynthia McKinney, and Jim Clyburn expanded their bases through voter registration and mobilization models pioneered by Jackson’s field teams. Their rise represented the tangible outcome of Jackson’s vision — that local empowerment could reshape national politics.

Jackson’s influence also reverberated through the Bill Clinton era, where veterans of the Rainbow Coalition became influential DNC strategists and policy voices. The Clinton–Gore campaigns of 1992 and 1996 adopted Jackson’s inclusive “big tent” approach, reaching out to working-class whites, Black church networks, Latino activists, and labor coalitions under a shared message of opportunity. This multiracial framework reshaped Democratic strategy for decades, paving the way for the diverse coalitions that would later elect Barack Obama and Kamala Harris.

Clinton White House — Remarks to the Rainbow PUSH Coalition • Congress.gov — Maxine Waters • House Archives — James Clyburn

The 1988 New York City Campaign

In New York City, Jackson ran a sophisticated campaign that included key black community political operatives like John Flateau, Bill Lynch, and Hulbert James. Hulbert James, a seasoned Brooklyn political operative, brought critical grassroots organizing expertise to Jackson’s NYC campaign. James had deep roots in Brooklyn’s Black community and understood the borough’s complex political terrain. His work on Jackson’s campaign and later on David Dinkins’s mayoral campaign demonstrated the continuity between these two historic electoral efforts—Jackson’s campaign built the infrastructure and energy that Dinkins would harness a year later to become New York City’s first Black mayor.

Jackson’s Chicago and DC based foundation, the Citizenship Education Fund, run by nationally recognized African American voting expert, Greg Moore, awarded GOTV grants to key groups to mobilize and turnout the Black and people of color vote.

Countdown 88 Rally at House of the Lord Pentecostal Church Brooklyn New York – On Stage Rosa Parks, to her right facing Crowd, Assemblyman Roger Green, to his Right, Countdown 88 Director, Selwyn Carter, to his Left, Dennis Rivera, President (SEIU) 1199, and to his left facing crowd and behind Rosa parks, Stanley Hill, Executive Director AFSCME DC 37

The Citizenship Education Fund teamed up with a New York City-wide voter registration and Get Out the Vote campaign named Countdown 88 to turn out the vote in New York City. Countdown 88, directed by another experienced community and voting rights operative, Selwyn Carter, was backed by one of New York City’s oldest and most prominent civic groups, the Community Service Society (CSS), led by respected civic leader, David R. Jones, and by a coalition of leading labor, civic, and church groups that included AFSCME District Council 37 and (SEIU) 1199.

David R. Jones — whose civic leadership at the Community Service Society of New York helped expand the conditions for Black electoral engagement in New York — comes from a lineage of public service shaped by his father, the late Judge Thomas R. Jones. His support for Countdown 88 and Countdown 89 aligned CSS with a broader movement for enfranchisement and laid groundwork for historic outcomes, including Jesse Jackson’s 1988 New York breakthrough and the city’s first Black mayoral victory.

Ney York City’s Black vote turned out in huge numbers, and Jackson created shockwaves when he won New York City. His New York City victory demonstrated that a mayoral candidate backed by a Black and Brown coalition could prevail in New York City. Thus, Jesse Jackson’s 1988 New York City presidential campaign victory became the launching pad for David Dinkins historic campaign to become the first African American mayor of New York City. This was a pattern that repeated itself across the country, as Jackson, through his historic presidential campaign’s mobilization of African American voters, demonstrated the power of the Black vote to elect local candidates.

🗳️ Local Coattail Victories Sparked by Jackson’s 1988 Campaign

🏙️ New York City – David Dinkins

- Jackson’s NYC win in the 1988 Democratic primary was unprecedented, powered, in part, by Countdown 88 and a coalition of Black and Brown voters.

- This surge laid the groundwork for David Dinkins’ 1989 mayoral victory, with many of the same operatives and organizations pivoting to support his campaign.

🌆 Chicago – Carol Moseley Braun

- Jackson’s Chicago base helped elevate Carol Moseley Braun, who won a U.S. Senate seat in 1992—becoming the first African American woman in the Senate.

- Her campaign drew on the same voter mobilization networks Jackson built during his runs.

🏛️ Atlanta – Maynard Jackson & Andrew Young

- While both were already prominent, Jackson’s Southern Super Tuesday momentum in 1988 reinforced the political infrastructure that supported Andrew Young’s mayoral tenure and Maynard Jackson’s return to office.

- Jackson’s campaign energized Black voter turnout in Georgia, where he won 94% of the Black vote.

🏞️ Alabama – Local Legislative Gains

- Jackson’s 1988 campaign drove record Black turnout in Alabama (96%), helping elect several Black candidates to local and state offices.

- These gains were especially notable in counties with historically low Black representation.

🏙️ Cleveland – Mayor Michael R. White

- Jackson’s campaign energized Black political networks in Ohio, contributing to the climate that helped elect Michael R. White as Cleveland’s mayor in 1989.

- White’s campaign echoed Jackson’s themes of coalition-building and urban empowerment.

📊 Timeline of Coattail Victories Sparked by Jackson’s 1988 Campaign

| Year | Milestone | Location | Candidate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Jackson wins NYC Democratic primary | New York City | Jesse Jackson |

| 1989 | David Dinkins elected first Black mayor | New York City | David Dinkins |

| 1989 | Michael R. White elected mayor | Cleveland, OH | Michael R. White |

| 1992 | Carol Moseley Braun elected to U.S. Senate | Illinois | Carol Moseley Braun |

| 1990s | Black legislators gain seats in statehouses | Alabama, Georgia | Multiple local candidates |

| 1993 | Jackson’s NVRA advocacy influences federal law | National | Jesse Jackson, Bill Lucy |

Jackson’s Ripple Effect

Andrew Young

Beyond American Borders: Jesse Jackson’s International Diplomacy

While Jackson’s presidential campaigns captured headlines, his work as a freelance diplomat demonstrated another dimension of his leadership—the ability to negotiate with foreign governments and secure the release of American hostages when official channels failed.

The Syria Mission (1983)

In December 1983, U.S. Navy pilot Lieutenant Robert Goodman was shot down over Lebanon and captured by Syrian forces. With U.S.-Syrian relations at a low point, the Reagan administration struggled to secure Goodman’s release. Jackson, acting on his own initiative and against the wishes of the State Department, traveled to Damascus to negotiate directly with Syrian President Hafez al-Assad.

After tense negotiations, Assad agreed to release Goodman as a gesture of goodwill. Jackson returned to the United States with Goodman, landing to a hero’s welcome. The mission demonstrated Jackson’s willingness to take risks and his ability to open doors through personal diplomacy, moral suasion, and appeals to shared humanity.

The Gulf War Mission (1990)

When Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990 and Saddam Hussein took hundreds of foreign nationals hostage, Jackson again traveled to Baghdad. Through personal meetings with Hussein, Jackson negotiated the release of several hundred hostages, including American and British citizens. His willingness to engage with a dictator whom U.S. officials refused to negotiate with drew both praise and criticism—but it brought people home.

The Kosovo Mission (1999)

In May 1999, during NATO’s bombing campaign against Yugoslavia, three U.S. soldiers were captured by Yugoslav forces. Jackson traveled to Belgrade and negotiated directly with President Slobodan Milošević, securing the soldiers’ release after 32 days in captivity. Once again, Jackson succeeded where official diplomacy had stalled.

These missions established Jackson as a unique figure in American foreign policy—neither an official representative nor a mere activist, but a moral intermediary who could reach across ideological and national divides. His success in these missions rested on his moral authority, his independence from government policy, and his ability to appeal to leaders’ desire for international legitimacy and respect.

Beyond the ballot, Jackson’s legacy is infrastructural. He built networks, trained organizers, and mentored generations of leaders. His work helped pave the way for the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), which expanded access to the ballot and modeled reform on grassroots innovations.

Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition wasn’t just a slogan—it was a strategy. It linked Black, Latino, Asian, Native, and white working-class communities in a shared fight for dignity. It challenged the idea that power must be monolithic, and proved that coalition could be transformative.

Beyond Politics: Jesse Jackson’s Cultural Impact and Symbolic Leadership

Jesse Jackson’s influence extends far beyond election results and policy victories. For more than five decades, he served as a moral voice for millions of Americans—a preacher-politician who could move seamlessly from the pulpit to the protest line, from corporate boardrooms to Capitol Hill.

The Moral Voice of Black America

Jackson emerged in the post-King era as one of the few Black leaders with both national visibility and moral authority. His Saturday morning broadcasts, syndicated radio program, and frequent media appearances made him a constant presence in American political discourse. For many Americans—particularly older Black Americans—Jackson’s voice was synonymous with Black political aspiration and moral clarity on issues of justice.

The Phrase-Maker

Jackson’s rhetorical gifts produced phrases that entered the American lexicon:

- “Keep Hope Alive” – His 1988 convention refrain became a rallying cry for progressive movements

- “I Am Somebody” – His PUSH-Excel chant affirmed Black children’s worth and potential

- “Down with dope, up with hope” – Anti-drug campaign slogan

- “Hands that picked cotton can now pick presidents” – Powerful metaphor for Black political empowerment

- “When we change the race problem into a class fight between the haves and the have-nots, then we are going to have a new ball game” – His vision of multiracial coalition politics

Saturday Morning Radio and Television Presence

For decades, Jackson’s Saturday morning radio programs reached millions of Black listeners. Combined with frequent appearances on Sunday morning political talk shows, Jackson maintained a media presence that kept civil rights and economic justice issues in national conversation even when other Black leaders lacked platforms.

Relationship with Hip-Hop and Youth Culture

Unlike many civil rights-era leaders, Jackson actively engaged with hip-hop culture and younger activists. While he sometimes criticized explicit lyrics, he also recognized hip-hop as a legitimate form of Black expression and attempted to build bridges between generations. Artists from Public Enemy to Kanye West referenced Jackson in their music, acknowledging his iconic status even as they sometimes challenged his methods.

The Complexity of Symbolic Leadership

Jackson’s role as a symbol of Black political aspiration came with burdens. He was simultaneously celebrated as a trailblazer and criticized for self-promotion. Some saw him as heir to King’s legacy; others viewed him as an opportunistic grandstander. What’s undeniable is that for millions of Americans—particularly those who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s—Jesse Jackson was their first encounter with the idea that a Black person could run for president.

His campaigns made Barack Obama possible, not just organizationally but imaginatively. Obama himself acknowledged this debt, even as his campaign sought to differentiate itself from Jackson’s style and approach.

Controversies and Criticism: The Complexity of Public Leadership

No assessment of Jesse Jackson’s legacy would be complete without acknowledging the controversies that marked his career and the criticism he faced from allies and opponents alike. Understanding these controversies provides a fuller, more honest picture of Jackson’s impact.

The “Hymietown” Incident (1984)

During his 1984 presidential campaign, Jackson referred to New York City as “Hymietown” in what he believed was a private conversation with a Black reporter. When the comment was published, it triggered a firestorm of criticism from Jewish leaders and organizations who saw it as anti-Semitic. Jackson initially denied making the comment, then downplayed its significance, before finally issuing a full apology at a synagogue in Manchester, New Hampshire.

The incident damaged Jackson’s relationship with many Jewish voters and leaders, particularly in New York, where Jewish-Black political coalitions had been essential to civil rights victories. While Jackson worked to repair these relationships—including traveling to Israel and meeting with Holocaust survivors—the controversy dogged his campaigns and required constant navigation by his political allies. During David Dinkins’s 1989 mayoral campaign, opponents attempted to use Dinkins’s association with Jackson as a wedge with Jewish voters, forcing Dinkins to carefully establish his independence.

Criticism from Within the Black Community

Jackson also faced substantial criticism from other Black leaders who viewed his style as too confrontational, too focused on media attention, or insufficiently rooted in traditional civil rights institutions. Coretta Scott King and other SCLC veterans were sometimes cool to Jackson, viewing him as having used King’s assassination to promote his own career. Other Black elected officials worried that Jackson’s rhetorical fire and outsider stance sometimes made coalition-building and legislative progress more difficult.

Some critics, including certain members of the Congressional Black Caucus, argued that Jackson’s presidential campaigns, while inspirational, siphoned resources and attention away from the hard work of electing Black officials at state and local levels. They worried that Jackson’s focus on the symbolic victory of a presidential campaign came at the expense of building sustainable Black political power in cities and states.

Criticisms from the Political Establishment

Mainstream Democratic leaders often viewed Jackson with suspicion and frustration. They worried that his campaigns would alienate white voters and doom Democratic chances in general elections. Party insiders resented his demands for influence in party affairs and his willingness to withhold endorsements to extract concessions. Some saw him as a “spoiler” who weakened Democratic nominees without offering a realistic path to victory himself.

Personal Life and Ethical Questions

In 2001, Jackson publicly acknowledged having fathered a daughter outside his marriage during an extramarital affair in the late 1990s. The revelation was particularly painful because it came shortly after Jackson had counseled President Bill Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, leading to charges of hypocrisy. Jackson largely withdrew from public life for several months, eventually returning to activism but never fully regaining his previous level of national prominence.

Financial and Organizational Questions

Rainbow/PUSH Coalition faced periodic scrutiny about its finances, fundraising practices, and the overlapping roles of Jackson’s political and nonprofit activities. Critics questioned whether corporations made donations to avoid Jackson-led boycotts—essentially a form of protection money—and whether Rainbow/PUSH’s operations were sufficiently transparent.

A Balanced Assessment

These controversies don’t erase Jackson’s achievements, but they complicate his legacy. They reveal a leader who was brilliant, flawed, ambitious, and transformative—fully human in his contradictions. Jackson’s greatest strength—his willingness to challenge power and speak uncomfortable truths—sometimes led him to make mistakes and antagonize potential allies. His drive for visibility and influence sometimes crossed into self-promotion. His moral authority was periodically undermined by personal failings.

Yet even Jackson’s critics acknowledge that he changed American politics permanently. He made it possible to imagine a Black president. He registered millions of voters. He trained a generation of political operatives. He forced the Democratic Party to take Black voters seriously. He championed economic justice when others focused narrowly on civil rights. Whatever his flaws, Jesse Jackson’s impact on American democracy is undeniable and enduring.

✊ Jesse Jackson’s Economic Impact

Jesse Jackson’s economic vision centered on empowering Black communities through targeted investment, corporate accountability, and coalition-building. His work extended the legacy of economic self-determination into electoral politics, labor negotiations, and national campaigns.

Key Strategies and Examples:

- Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity): Founded in 1971, PUSH pressured major corporations to hire Black workers, invest in Black-owned businesses, and diversify their supply chains. Jackson negotiated with companies like Coca-Cola and Burger King to expand Black economic participation.

- PUSH-Excel Program: A youth-focused initiative that linked education, economic opportunity, and civic engagement. It encouraged academic achievement while connecting students to internships and job pipelines.

- Wall Street Project (1996): Jackson launched this initiative to challenge exclusionary practices in finance. It advocated for minority inclusion in boardrooms, banking, and investment portfolios, pushing for supplier diversity and equitable lending.

- Economic Justice in Campaigns: During his 1984 and 1988 presidential runs, Jackson elevated economic justice as a national issue—calling for urban reinvestment, fair wages, and support for family farms. His platform helped shape the Democratic Party’s approach to poverty and race.

- Support for Black Farmers and Labor Unions: Jackson was a vocal ally of Black farmers fighting discriminatory USDA practices, and he supported unionized labor as a pathway to economic stability.

Jackson’s model fused protest with negotiation, grassroots organizing with boardroom advocacy. He didn’t just demand change—he brokered it, building bridges between Wall Street and Martin Luther King Boulevard.

Today, Jackson’s legacy lives on in every multiracial movement, every grassroots campaign, and every effort to expand democracy. He showed that Black leadership could be national, visionary, and unapologetically rooted in justice.

The Jackson Legacy: Measuring Impact Across Generations

As Jesse Jackson faces declining health and the twilight of his remarkable life, it’s essential to measure his full impact on American politics, Black empowerment, and democratic participation. His legacy operates on multiple levels—electoral, institutional, symbolic, and personal.

Electoral Infrastructure: The Foundation for Future Victories

Jackson’s most tangible legacy is the electoral infrastructure he built. Between his 1984 and 1988 campaigns, Jackson registered an estimated 2-3 million new voters—predominantly Black, Latino, young, and poor. But the impact extended far beyond raw numbers:

Voter Registration as Movement Building: Jackson’s campaigns transformed voter registration from a technical exercise into a movement activity—connecting people’s personal grievances to political power. The massive registration drives organized by Jackson’s field teams created networks that outlasted his campaigns.

Field Operations and Data: Jackson’s campaigns pioneered modern field operations in Black communities, developing voter files, precinct targeting strategies, and turnout models that subsequent campaigns built upon. The techniques his campaigns developed became standard practice in Democratic politics.

Local Candidate Development: The infrastructure Jackson built elected mayors (David Dinkins in New York, Michael R. White in Cleveland), senators (Carol Moseley Braun in Illinois), and hundreds of state and local officials. His campaigns proved that mobilizing Black voters could change the entire electoral landscape—a lesson that resonates in every election since.

The Obama Connection: Making the Impossible Imaginable

Jesse Jackson made Barack Obama possible. This isn’t just historical myth—it’s demographic, organizational, and psychological reality:

Demographically: Obama’s campaign in 2008 relied on the expanded Black electorate that Jackson helped create. The millions of Black voters registered during the 1980s and maintained through subsequent cycles formed the base for Obama’s breakthrough in Southern primaries.

Organizationally: Many Obama campaign operatives—from field directors to senior strategists—cut their teeth on Jackson campaigns or were mentored by Jackson veterans. The Rainbow Coalition’s emphasis on diverse, multiracial organizing directly informed Obama’s 50-state strategy.

Psychologically: Jackson proved that a Black candidate could win primaries, compete nationally, and inspire millions. He shattered the ceiling even if he couldn’t break through it completely. Obama acknowledged this debt both publicly and privately, even as his campaign sought to avoid the specific mistakes Jackson made and the controversies that surrounded him.

The tension between Jackson and Obama in 2008—captured in a hot‑mic moment where Jackson made critical comments about Obama—reflected generational differences and personal rivalry. But it didn’t erase the historical reality: without Jackson’s campaigns, Obama’s candidacy would have been unthinkable. That truth was visible on election night in Chicago’s Grant Park, where Jackson stood in the crowd openly weeping as Obama delivered his victory speech, a moment that symbolized the bridge between their two eras.

Training Ground for Democratic Leadership

Jackson’s campaigns and organizations served as training grounds for a generation of Democratic political operatives, strategists, and elected officials:

DNC Leadership: Minyon Moore (DNC official and convention co-chair), Donna Brazile (interim DNC Chair), and Ron Brown (first Black DNC Chair) all emerged from Jackson’s campaigns.

Congressional Leadership: Maxine Waters credited Jackson with teaching her coalition politics. James Clyburn’s South Carolina organization was strengthened by Jackson’s 1988 Southern strategy.

Gubernatorial Politics: Virginia Governor Douglas Wilder’s historic 1990 victory was built on infrastructure Jackson helped create.

State and Local Power: Thousands of campaign workers, precinct captains, and volunteers who worked on Jackson campaigns went on to run local campaigns, serve on school boards, win state legislative seats, and build community organizations.

Economic Justice Framework: Linking Civil Rights to Economic Power

Jackson’s insistence that civil rights without economic power was incomplete reshaped how progressives think about justice:

Corporate Accountability: Operation PUSH’s boycotts and negotiations with major corporations established the principle that companies operating in Black communities owed something back—jobs, investment, Black-owned business opportunities.

Wall Street Project: Jackson’s 1990s push for minority inclusion in financial services anticipated contemporary debates about economic inequality and financial regulation.

Labor Coalition: Jackson’s alliance with organized labor—particularly through Bill Lucy and CBTU—helped maintain the Black-labor coalition that remains essential to progressive politics.

Language of Economic Justice: Jackson’s campaigns elevated economic inequality, corporate power, and wealth concentration as central political issues. His 1988 campaign’s focus on economic justice anticipated Bernie Sanders’s 2016 and 2020 campaigns by nearly three decades.

The Multiracial Coalition Model

Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition—despite never fully achieving its vision—provided a model for multiracial progressive politics:

Beyond Black Politics: Jackson insisted that Black political power required coalition with Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, progressive whites, and labor. This vision of multiracial working-class politics continues to shape progressive strategy.

LGBTQ+ Inclusion: Jackson’s embrace of LGBTQ+ rights in the 1980s—when AIDS was decimating communities and most politicians avoided the issue—demonstrated moral leadership that was decades ahead of his party.

Issue-Based Coalition: Jackson showed that coalitions could be built around shared economic interests and common values rather than identity alone. His campaigns brought together farmers, factory workers, students, and activists around a shared vision of economic justice.

Institutional Changes to Democratic Politics

Jackson’s campaigns forced institutional changes to the Democratic Party that made it more representative and democratic:

Delegate Selection Reform: Jackson’s protests about the 1984 “winner-take-all” delegate rules led to reforms that made the nomination process more proportional and gave insurgent candidates better chances.

Party Diversity: Jackson’s campaigns accelerated the diversification of Democratic Party leadership, convention delegates, and campaign staffs. The party couldn’t ignore Black voters’ demands after Jackson proved their electoral power.

Platform Influence: Many planks of Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 platform—from sanctions on South Africa to healthcare reform—eventually became Democratic Party orthodoxy.

Cultural and Symbolic Legacy

For millions of Americans, Jesse Jackson represents possibility:

First Major Black Presidential Candidate: Jackson showed a generation of Black children that they could aspire to the presidency. Every Black candidate since—from Obama to Kamala Harris to Cory Booker—walks a path Jackson cleared.

Moral Voice: In an era when civil rights leaders have less prominent platforms, Jackson’s decades as a moral voice established the archetype of the preacher-politician who could speak truth to power.

Generational Bridge: Jackson connected the civil rights generation to hip-hop culture, student activists, and contemporary movements. He served as a living link between King’s era and contemporary struggles.

The Incomplete Revolution

Jackson’s legacy is also a reminder of how far America still has to go:

Unfinished Economic Agenda: The economic inequality Jackson railed against has only worsened. Wealth gaps between Black and white Americans remain vast.

Voter Suppression: The voting rights Jackson fought to expand are under renewed assault through voter ID laws, polling place closures, and new barriers to ballot access.

Political Barriers: While Jackson made Black presidential candidates imaginable, institutional barriers remain—from campaign finance requirements to media gatekeeping to persistent racial prejudice.

Personal Impact: The Thousands Who Say “Jesse Jackson Changed My Life”

Beyond the statistics and electoral victories, Jackson’s legacy lives in the thousands of individuals whose lives he touched:

- The campaign volunteer who became a city councilmember

- The student who registered to vote after hearing Jackson speak

- The community organizer inspired by his courage

- The corporate employee who got hired because of PUSH negotiations

- The hostage family reunited because of his diplomacy

- The millions who voted for the first time because he asked them to

These individual transformations—multiplied across decades and millions of people—may be Jackson’s most enduring legacy.

Measuring the Man Against the Moment

Jesse Jackson’s life and career intersected with nearly every major development in post-civil rights Black politics:

- He worked with Martin Luther King Jr. and witnessed the end of the civil rights movement’s first phase

- He pioneered economic justice organizing in the 1970s

- He ran groundbreaking presidential campaigns in the 1980s

- He engaged in international diplomacy in the 1990s

- He witnessed the election of Barack Obama

- He lived to see renewed struggles over voting rights and racial justice in the 2020s

Was he perfect? Far from it. Did he make mistakes? Absolutely. Did he sometimes put personal ambition ahead of collective good? His critics would argue yes. But perfection isn’t the measure of historical significance. Impact is.

By that standard, Jesse Jackson’s legacy is secure. He expanded American democracy. He registered millions of voters. He trained generations of leaders. He made the impossible imaginable. He forced America to confront its economic and racial injustices. He showed that Black leadership could be national, visionary, and transformative.

When the history of late 20th-century American politics is written, Jesse Jackson will occupy a central chapter—not despite his contradictions and controversies, but as a fully human figure whose audacity, vision, and determination changed the country forever.

As Jackson himself might say: He proved that those who were written out of history could write themselves back in. He showed that hands that picked cotton could indeed pick presidents. He kept hope alive.

That is legacy enough for any life.

Post‑Mortem Epilog

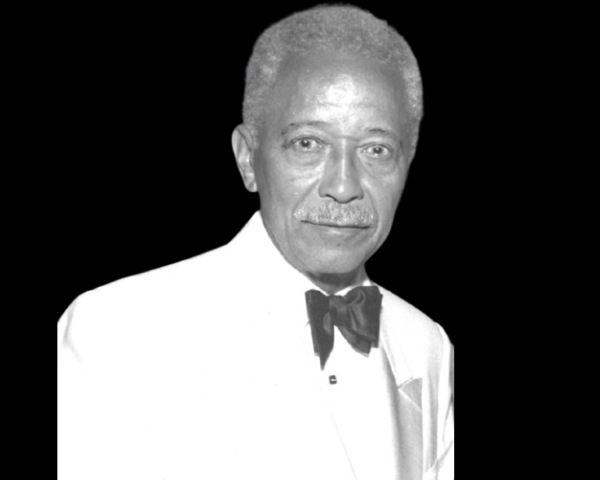

Today, February 26, 2026, as Rev. Jesse Louis Jackson, Sr. lies in state at the Rainbow/PUSH Headquarters in Chicago, this pillar post takes on a different meaning than when it was written. The analysis above was completed before his passing on January 20, 2026, at a time when his influence was still actively shaping political and movement life.

Nearly every member of the Black Politics Advisory Council — including the Editor‑in‑Chief — intersected with Jackson’s work across different decades and geographies. His campaigns, coalitions, and organizing traditions formed part of the civic environment in which many of us learned, organized, and came of age. Those intersections are not claims of proximity or authority; they are acknowledgments of how deeply Jackson’s work structured the political world we inherited.

The mission of Black Politics is rooted in preserving that lineage: documenting the leaders, networks, and organizing traditions that shaped our generation so that younger readers can see the architecture of the movements they now inherit. Jackson’s passing underscores the urgency of that work. The institutions he built, the leaders he mentored, and the coalitions he assembled continue to define the civic landscape of the present.

This post remains unchanged from its original form so that readers can see the analysis as it was written — before the historical frame shifted. It now stands as both a historical account and a marker of a life whose impact will continue to shape the work of this publication and its Advisory Council.

Editor’s Note: The Editor‑in‑Chief of Black Politics has participated in movement and political organizing connected to Rev. Jesse Jackson since 1988, beginning with his role as director of Countdown ’88 during Jackson’s presidential campaign. He later served on the steering committee of the New York City Nelson Mandela Welcoming Committee, standing on the Harlem and Brooklyn stages during Mandela’s historic 1990 visit. Over the decades, he has been an activist participant in Rainbow Coalition and labor events in Selma, Atlanta, and across the South, including multiple Selma‑to‑Montgomery commemorations such as the 30th anniversary march in 1995, where he walked and helped direct marchers the entire distance and joined dozens speaking on the Alabama Capitol steps. He also worked in the broader civic environment shaped by Jackson’s leadership during the Florida recount in Palm Beach. Across more than three decades, he has been present in numerous Jackson‑related marches, organizing efforts, and civic mobilizations throughout the South — always as an activist or leader working within the movements Jackson helped shape.

Jesse Jackson & Rainbow Coalition

September 30th, 2025