The Harlem Gang of Four Political Strategy That Changed NYC Forever

How Four Harlem Leaders Built the Coalition That Elected New York’s First Black Mayor

Harlem Gang of Four political strategy: Famous Harlem politicians built infrastructure, registered 250,000 voters and elected the first Black mayor of New York.

The Harlem Gang of Four political strategy transformed New York City’s power structure through systematic infrastructure building, strategic voter mobilization including Countdown 88, and calculated coalition-building that elected the city’s first Black mayor and demonstrated how collective organizing could build sustainable Black political power.

Who was the first Black mayor of New York?

David Dinkins became the first Black mayor of New York in 1990, serving until 1993. His election resulted from decades of strategic planning by the Harlem Gang of Four, who facilitated the building of the political infrastructure and multiracial coalition necessary to win citywide office. Dinkins’ victory demonstrated that systematic organization could overcome the barriers that had previously prevented Black candidates from winning New York’s mayoralty.

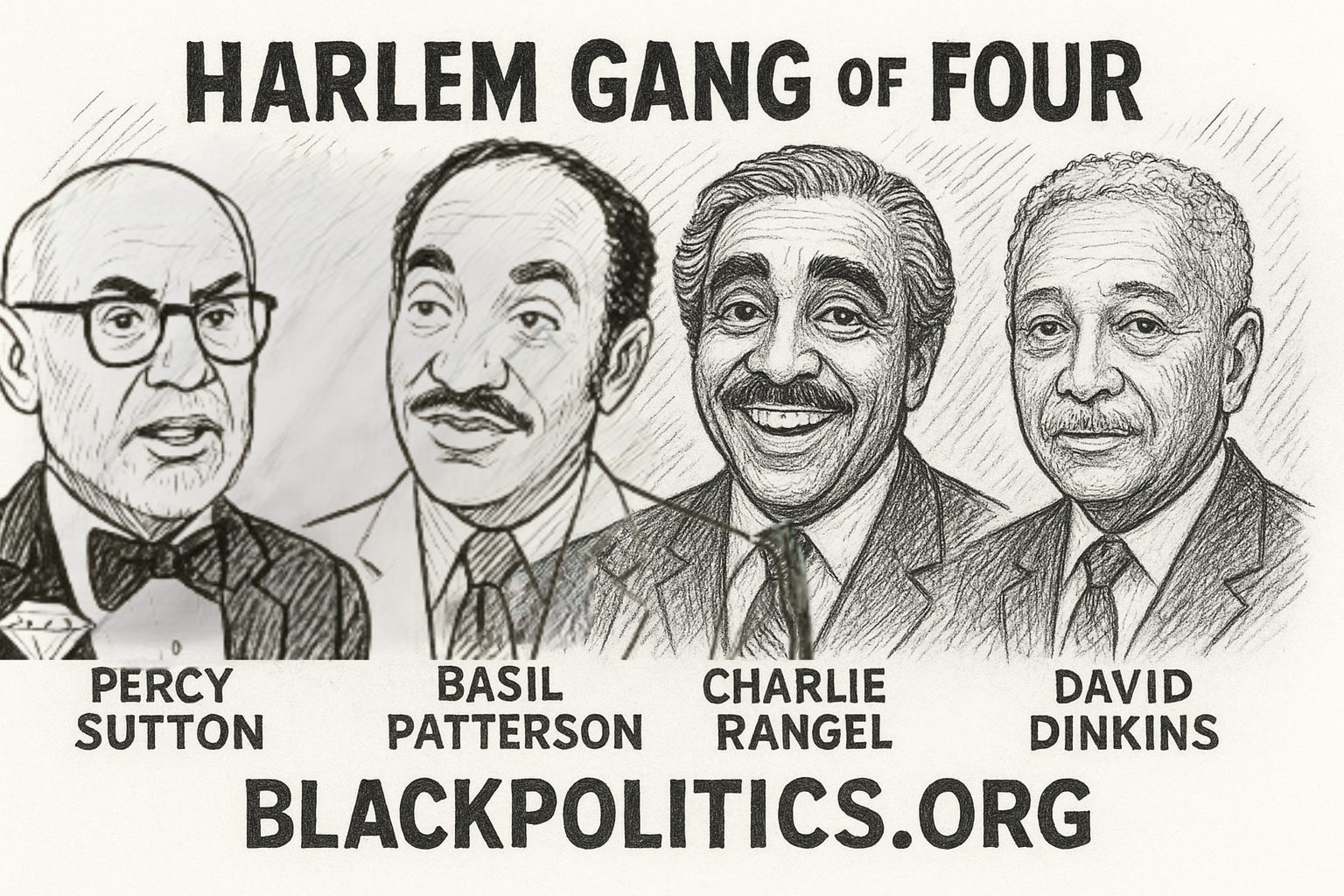

Harlem Gang of Four – Charles Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, David Dinkins

What did the gang of four do?

The Harlem Gang of Four—Charles Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and David Dinkins—built sustainable political infrastructure in Harlem and across New York City. Their strategy included working to set up a campaign to register over 250,000 new voters through Countdown 88, coalescing with African American, Latino, and progressive organizations and leaders in the other boroughs, electing Black officials to key positions, and ultimately electing David Dinkins as New York’s first Black mayor in 1989. Unlike previous political movements that relied on charismatic individuals, the Gang of Four collaborated to emphasize institutional power and coalition-building.

“The Harlem Gang of Four political strategy—developed by Harlem Gang of Four members Congressman Charles Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and David Dinkins—was instrumental in building the infrastructure responsible for electing David Dinkins mayor of New York City. This approach to building Black political power NYC 1980s gave birth to Countdown 88 voter registration, a citywide mobilization campaign that created a blueprint for electoral organizing.

Bill Lynch NYC strategist, working with the Harlem Gang of Four, recruited activist Selwyn Carter to direct Countdown 88, which was sponsored by the Community Service Society of New York (CSS) under the leadership of David R. Jones. Lynch, Carter, and Jones helped forge Countdown 88’s political alliance that included labor, religious, civil rights and community groups. This alliance significantly increased voter registration beyond the 1984 efforts by Al Vann and the Brooklyn based Coalition for Community Empowerment and drove massive mobilization in the 1988 presidential primary. Jesse Jackson won New York City in that primary, signaling the potential of Black and brown voters to lead a transformational coalition. In 1989, Harlem Gang of Four member David Dinkins built upon that mobilization and was elected mayor of New York City.

How many Black mayors has NYC had?

New York City has had two Black mayors: David Dinkins (1990-1993) and Eric Adams (2022-present). Dinkins’ historic election in 1989 proved that the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy could overcome entrenched political power, paving the way for future Black political leadership in New York City. Across the East River in Brooklyn, Al Vann, a key founder of the the Coalition for Community Empowerment, was a mentor to Eric Adams.

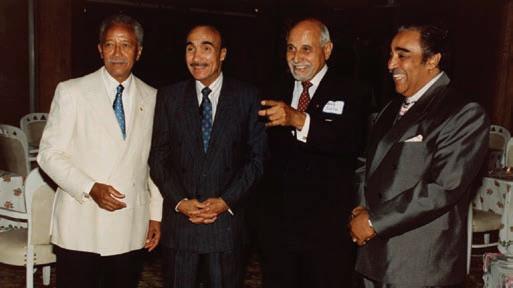

Through strategic coalition-building, institutional infrastructure, and calculated risk-taking, the Harlem Gang of Four built a political machine that not only elected the city’s first Black mayor but influenced presidential campaigns, Congress, and the New York State Governor’s office, creating a blueprint for Black political power that still resonates today. Harlem Gang of Four members Charlie Rangel and David Dinkins reached the pinnacle of elective office in their respective spheres. Rangel became chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, one of the most powerful positions in the United States Congress. Dinkins will always be known as the first African American mayor of New York City. However, things might have been different had the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy played out the way they originally intended.

Conventional wisdom held that Percy Sutton would be the first Black mayor of New York, having served as the powerful Manhattan Borough President before Dinkins. Basil Paterson was the first African American to run statewide in New York on a major party ticket. Despite being the highest vote-getter on his ticket in 1970, he was passed over by Democrats for the 1974 gubernatorial race. After subsequently being appointed deputy mayor of New York City, he stepped down to accept appointment as New York Secretary of State in 1979, making him the highest-ranking African American statewide official at that time. His son, David Paterson, ended up becoming Governor after Eliot Spitzer’s resignation in March 2008 due to a prostitution scandal. As Lieutenant Governor, the younger Paterson was next in the line of succession and was sworn in as the 55th Governor on March 17, 2008.

Following Jesse Jackson’s victory in the 1988 presidential primary in New York City, there was speculation that Basil Paterson might run for mayor, but he had previously declined a mayoral run in 1984 citing pressing family problems, leaving the field for David Dinkins to become the first of the Harlem Gang of Four members to be elected mayor of New York City in 1989.

What does “Gang of Four” mean in Harlem politics?

The “Gang of Four” in Harlem politics refers to four Black political leaders—Charles Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and David Dinkins—who formed a political alliance in the 1960s and 1970s. This was not a formal organization like Brooklyn’s Coalition for Community Empowerment, but four individuals, David Dinkins, Basil Paterson, Charlie Rangel, and Percy Sutton strategizing together. The name emphasized their collective approach to power-building, contrasting with the individual-focused politics of earlier eras. The Harlem Gang of Four political strategy prioritized institutional infrastructure over personality-driven campaigns.

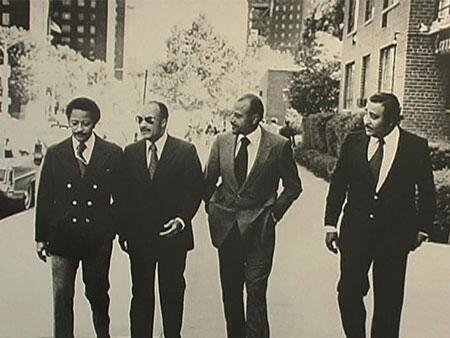

Origins: Four Men, One Vision

Who were the famous Harlem politicians of the 1970s-1990s?

The most famous Harlem politicians of this era were the Harlem Gang of Four: Congressman Charles Rangel, Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton, New York Secretary of State Basil Paterson, and Mayor David Dinkins. While Adam Clayton Powell Jr. had been Harlem’s dominant political figure in earlier decades, the Gang of Four represented a new model of collective political organizing that transformed New York City politics.

The Harlem Gang of Four emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as four ambitious, politically astute Black leaders who recognized that individual achievement would never match collective power. Each brought distinct strengths to the alliance, creating a formidable political force that would dominate New York City politics for decades.

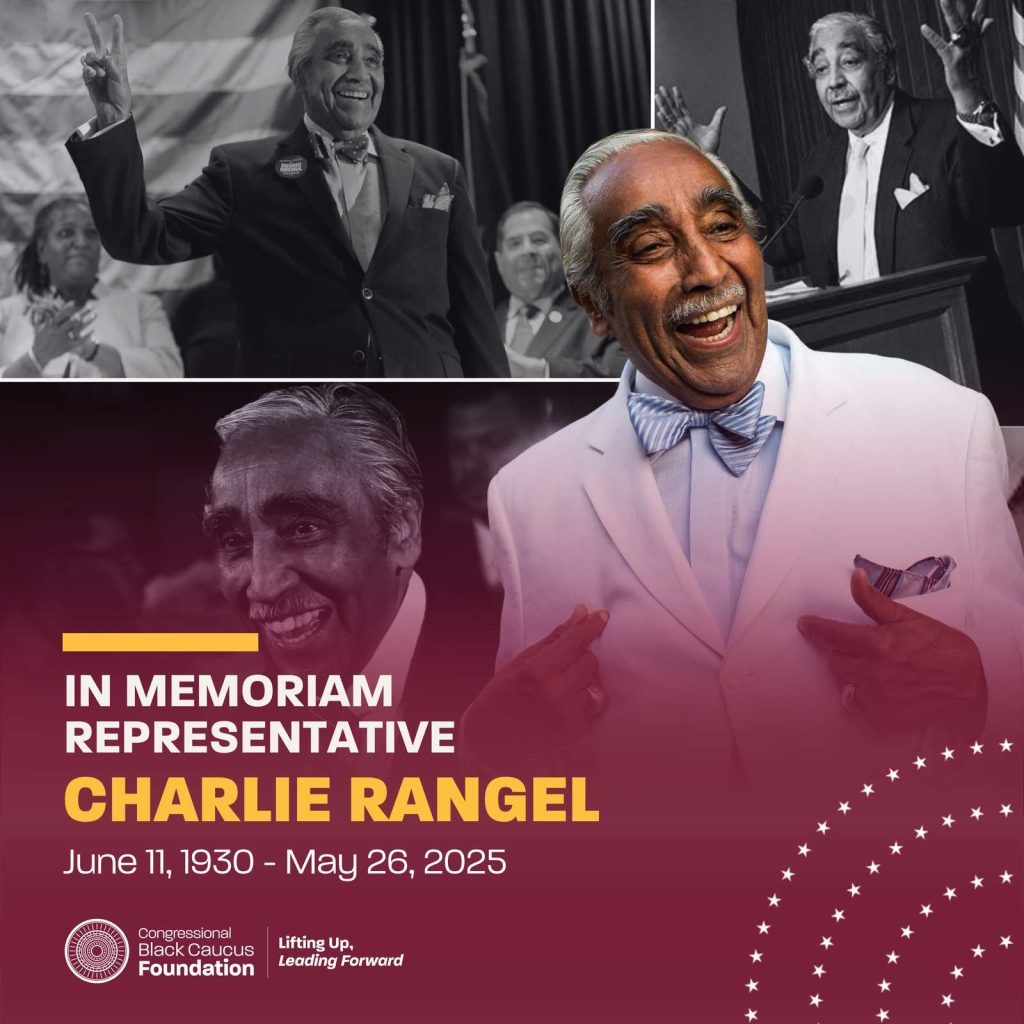

Charles B Rangel: The Congressional Power Broker

Former Congressman Charles Rangel’s political journey began in the streets of Harlem, where he grew up in poverty before serving in the Korean War and earning a law degree. Charlie Rangel was a towering figure in New York and national politics. He died in May 2025 at the age of 94. Rangel, the last of the Harlem Gang of Four members, was a Democratic icon and a Harlem political institution who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for 23 terms. This made him one of the longest-serving lawmakers in Congress and a key architect of numerous legislative achievements over nearly five decades. Charles Rangel wife, Alma died in 2024.

Charles B Rangel first came to national prominence in 1970 when he accomplished what many thought impossible: Rangel defeated the legendary Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in the Democratic primary for New York’s 16th Congressional District. That victory marked the beginning of a storied political career during which Rangel became known as a tireless advocate for his constituents and a powerful voice on issues of civil rights, social justice, economic reform, and education. A founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus Rangel helped shape the Democratic Party’s approach to urban policy and minority rights through some of the most turbulent decades in American politics.

This victory over Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. wasn’t just personal—it signaled a generational shift in Harlem politics. Rangel brought a different style than Powell: less flamboyant, more institutional, deeply strategic. He understood that Black political power required not just charisma and protest, but mastery of committee assignments, legislative procedure, and budget negotiations.

Born and raised in Harlem, Rangel was deeply shaped by his community and never strayed far from its pulse. After serving heroically in the Korean War—earning a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star—he used the G.I. Bill to attend New York University and later St. John’s University School of Law. His military service was often cited as a core influence on his sense of duty justice and public service.

Rangel’s legacy in Congress is marked by his tenure as chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee where he played a central role in shaping tax policy, healthcare reform, and trade agreements. He used this position to channel resources to Harlem, advocate for the Caribbean and African diaspora, and mentor younger Black politicians. His congressional seat became a platform for amplifying the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy and broader agenda. Known for his charisma, sharp wit and no-nonsense style, Rangel was both respected and feared on Capitol Hill. The City College of New York (CCNY), where he was Statesman in Residence after retiring from Congress in 2017, praised him as “a champion for his Big Apple constituents” and “the most effective lawmaker in Congress ” citing his record of having passed more legislation than any of his peers during his time in office. CCNY, located on a hill overlooking Harlem, is also home to the Charles B. Rangel Center for Public Service and the Charles B. Rangel Infrastructure Workforce Initiative. Rangel and his predecessor, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. were the two most famous Harlem politicians in mordern times.

Rangel was also one of the Harlem Gang of Four members, a political coalition from Harlem that included David Dinkins, Basil Paterson, and Percy Sutton—four influential Black leaders who redefined New York City’s political landscape in the late 20th century. Together they built a legacy of African-American political empowerment and helped open doors for generations of leaders to come.

Though Rangel’s career was not without controversy—he faced ethics investigations late in his tenure—he remained a beloved figure in Harlem and a respected elder statesman in Democratic politics. His ability to work across the aisle, and his deep understanding of legislative process made him a key player in countless negotiations and policy breakthroughs.

Rangel retired from Congress in 2017 leaving behind a legacy of service, advocacy, and transformation. His death marked the end of an era for Harlem and for the nation. He was remembered as a fierce advocate, a consummate public servant, and a man who never stopped fighting for the people he represented.

As a member of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee—and later its chairman—Rangel wielded influence over tax policy, trade, and Social Security.

Rangel’s role within the Gang of Four was that of the federal connector—the member who could leverage Washington power for New York priorities and his home village of Harlem, secure funding for community programs, and elevate local issues to the national stage.

Percy Sutton: The Media Mogul and Strategic Visionary

Among the Harlem Gang of Four members, Percy Sutton was the master strategist and its most entrepreneurial member. A Tuskegee Airman, civil rights lawyer, and former Manhattan Borough President, Sutton understood that political power required economic infrastructure and cultural visibility. Back then, before New York City restructured, the unelected Board of Estimate held all of the power. As the Boro President of Manhattan, Sutton had a seat on the powerful Board of Estimate. For over a decade (1966-1977), Percy Sutton as Manhattan Borough President was the highest-ranking African American elected official in New York State. He used this position to launch a bid for Mayor in 1977; however, his candidacy did not succeed.

Sutton’s 1977 mayoral campaign faced unexpected obstacles when Mayor Abraham Beame chose to run for re-election rather than step aside as some had anticipated. The campaign was further damaged by racial backlash following the July 1977 blackout, when looting and arson reinforced racial stereotypes. Despite Sutton’s attempts to appeal to white voters with strong anti-crime positions, polls suggested many New Yorkers focused primarily on the color of his skin. Sutton later called the experience ‘the most disheartening, deprecating, disabling’ of his career.

In 1972, Sutton purchased WLIB-AM, New York’s first Black-owned radio station, and later expanded into Inner City Broadcasting, which included the iconic WBLS-FM. These media properties became critical tools for Black political mobilization in New York City. When the Gang of Four needed to reach Black voters, they had direct access to the most influential voices in the community.

Sutton’s vision extended beyond politics. He recognized that Black political power would remain fragile without economic self-sufficiency. He invested in businesses, promoted Black entrepreneurship, and advocated for minority contracting and procurement policies that would create a Black middle class with a stake in the political system.

As a key architect of the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy, Sutton was calculating and patient. He understood timing, coalition dynamics, and the long game. When the Gang of Four made their move to elect David Dinkins mayor, it was Sutton’s strategic blueprint that guided the campaign.

Legal Career & Civil Rights Leadership

Percy Sutton’s legal career established him as one of the nation’s most prominent civil rights attorneys. After graduating from Brooklyn Law School in 1950 while working simultaneously as a post office clerk and subway conductor, Sutton opened his Harlem law firm in 1953 with his brother Oliver and partner George Covington. The firm quickly became a powerhouse of civil rights defense, representing over 200 defendants arrested during the 1963-64 civil rights marches in the South.

Stokely Carmichael, Malcolm X, and Betty Shabazz

Sutton served as branch president of the New York City NAACP from 1961 to 1962, participating in Freedom Rides where he was arrested and jailed alongside activists like Stokely Carmichael—an experience that endeared him to the Harlem community and demonstrated his willingness to place himself in harm’s way for justice. His most famous client was Malcolm X, whom he represented for a decade until Malcolm’s assassination in 1965. Sutton’s commitment to Malcolm X’s family extended far beyond legal representation; he and his brother Oliver helped cover the funeral expenses and supported Malcolm’s widow, Betty Shabazz, for decades afterward. In one of the most painful cases of his career, Sutton and David Dinkins defended Malcolm’s grandson, 12-year-old Malcolm Shabazz, when the troubled youth accidentally set a 1997 fire that killed his grandmother Betty—Sutton visited the boy nearly every day in jail for months, demonstrating the depth of his loyalty and compassion.

The Business Empire & Source of Wealth

Percy Sutton built one of the most successful African American business empires of the 20th century, with wealth rooted in media, real estate, and strategic investments. In 1971, while still serving as Manhattan Borough President, Sutton co-founded Inner City Broadcasting Corporation with his brother Oliver, legendary DJ Hal Jackson, and over fifty shareholders including David Dinkins and Betty Shabazz. Inner City purchased WLIB-AM for $1.9 million, making it New York City’s first Black-owned radio station. In 1974, the company acquired WBLS-FM, which became the number-one rated radio station in the nation by 1980 with the largest listening audience of any station in the country. Under Sutton’s leadership as chairman, Inner City Broadcasting expanded to own 19 radio stations across the country in cities including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit, and San Antonio—his Texas hometown. The company’s programming model of R&B music, talk radio, and community service was replicated nationwide, earning Sutton the nickname “Godfather of Urban Radio.” Inner City Broadcasting’s success made it a mainstay on Black Enterprise’s BE 100s list for more than two decades, with Sutton’s estimated net worth reaching $170 million by the end of the 1980s. Beyond broadcasting, Sutton formed Percy Sutton International, Inc., with investments encouraging agriculture, manufacturing, and trade in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Brazil. He also co-founded African Continental Telecommunications Ltd (ACTEL) in the 1990s and later Synematics, an IT company where he remained actively involved in day-to-day operations well into his eighties.

The Apollo Theater Acquisition & Harlem Revitalization

In 1981, Sutton made perhaps his most culturally significant business move when Inner City Broadcasting purchased the legendary Apollo Theater at a bankruptcy sale for $225,000. The 1,500-seat venue on West 125th Street, which had launched the careers of artists from Ella Fitzgerald to Michael Jackson, had fallen into disrepair—when Sutton took over, “the only ones here were the rats and the roaches,” as Rev. Al Sharpton later recalled. Sutton spearheaded a $20 million renovation that included building a cable television studio, and the theater reopened in 1985 as both a concert hall and national landmark. The renovation proved crucial to the broader revitalization of Harlem that is so evident today; 125th Street transformed from a struggling commercial strip into a bustling thoroughfare with a healthy mix of national retail chains and local businesses. Inner City Broadcasting produced the syndicated television show “It’s Showtime at the Apollo,” which first aired on September 12, 1987, and became a cultural phenomenon that raked in millions while showcasing Black talent to a global audience. However, a 1998 investigation by New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer found that members of the nonprofit Apollo Theatre Foundation, led by Charles Rangel, had retained revenues from the show that should have gone to the theater. The controversy resulted in Rangel stepping down as foundation chairman and Time Warner taking over operational control. Despite this painful ending, Sutton’s vision had secured the Apollo’s future—as Jonelle Procope, president and CEO of Apollo Theater Foundation, later said: “The Apollo and its staff stand on the shoulders of Mr. Sutton.”

Eric Holder, Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton Mentorship & Political Legacy

Percy Sutton’s influence extended far beyond his own achievements through his extraordinary mentorship of the next generation of Black political leaders. New York Governor David Paterson called Sutton “a friend and mentor,” crediting him with encouraging his entry into politics—Sutton was the one who told David Paterson he should run for the State Senate. Rev. Jesse Jackson, whom Sutton advised during both his 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns, considered him a pivotal mentor in his political career. Rev. Al Sharpton recalled meeting Sutton at age 12, and four years later, when the teenage Sharpton couldn’t afford to attend a national Black political convention, Sutton paid for his trip. U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said at Sutton’s funeral: “I admired, respected and worked for him. The opportunities given to my generation were paid for by the hard work and sacrifice of his. Without him, there would be no me.” David Dinkins acknowledged that Sutton’s distinguished 1977 mayoral campaign paved the way for his own 1989 run: “Because he ran for mayor in 1977 with such class and distinction that nobody laughed at me when I dared try in ’89.” Charles Rangel credited Sutton with encouraging him to run for Congress in the first place. President Barack Obama called Sutton “a true hero” whose “life-long dedication to the fight for civil rights and his career as an entrepreneur and public servant made the rise of countless young African-Americans possible.” As Sharpton eulogized: “Every time a Black politician walks in a legislature hallway, that’s Percy Sutton. Every time a black radio station plays black music, that’s Percy Sutton. Every time talk radio registers voters and mobilizes those that fight for justice, that’s Percy Sutton. He took the megaphones out of our hands and gave us a radio station—he made us important.”

Basil Paterson: The Behind-the-Scenes Operator

Basil Paterson was the Gang of Four’s consummate insider—the skilled negotiator who could work the room, broker deals, and build bridges across racial and ideological lines. A Harlem-born lawyer who served in the New York State Senate, Paterson became the first Black Secretary of State of New York and later served as Deputy Mayor under Ed Koch.

Paterson’s strength was his ability to operate in white political spaces without sacrificing Black interests. He understood the Democratic Party machinery, cultivated relationships with labor unions, and knew how to navigate the complex world of New York City and state politics.

Within the Gang of Four, Paterson was the bridge-builder and the closer. When negotiations required finesse, when coalitions needed to be expanded, when deals needed to be sealed—Paterson was the one who made it happen.

Caribbean Roots & Garvey Legacy: Immigrant Son to Harlem Power Broker

His son, David Paterson, would later become New York’s first Black governor, a testament to the political dynasty and infrastructure the Gang of Four helped build. Basil Alexander Paterson was born on April 27, 1926, in Harlem to Caribbean immigrant parents whose own experiences shaped his commitment to civil rights. His father, Leonard James Paterson, was born on the island of Carriacou in the Grenadines and arrived in New York City in 1917, while his mother, Evangeline Alicia Rondon, was born in Kingston, Jamaica, and worked as a stenographer and secretary for Black Nationalist leader Marcus Garvey—exposing young Basil to Garvey’s Pan-African activism from an early age. Paterson’s encounters with racism began early and never left him. At age 16, after graduating from De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx in 1942, he took his first job at a wholesale house in the old Port Authority building. Years later, Paterson described a painful ritual: “Every year there would be a Christmas party for the employees at some local hotel. Those of us who worked in the shipping department were black. We got paid not to go to the party.” This indignity, among many others, forged his determination to fight for dignity and equality through the law. His education at St. John’s University was interrupted by two years of honorable service in the U.S. Army during World War II, but he returned to earn his B.S. degree in biology in 1948 and his J.D. from St. John’s University Law School in 1951. While at St. John’s, he joined the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, beginning a lifelong commitment to community service organizations that would define his career.

Labor Law Mastery & Union Representation

After passing the New York bar in 1953, Paterson dedicated his career to labor law, becoming one of the most respected labor attorneys and negotiators in New York history. He began investigating discrimination for the New York State Commission Against Discrimination in 1952, then practiced labor law with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union after admission to the bar. Over the course of his career, Paterson provided counsel to more than 40 unions, focusing particularly on healthcare and municipal workers. From 1972 to 1977, he served as president of the Institute for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, honing skills that would make him indispensable during New York City’s fiscal crisis. His client list read like a who’s who of New York’s labor movement: the United Federation of Teachers, Transport Workers Union Local 100, SEIU 1199 (Hospital and Health Care Employees Union), the Service Employees International Union’s New York City local representing thousands of restaurant and hotel employees, and United Healthcare Workers East. In 1983, Paterson joined the prestigious law firm Meyer, Suozzi, English & Klein, where he co-chaired the labor practice group and represented clients in collective bargaining and arbitration matters well into the 2000s. His expertise proved crucial in several historic labor victories, including the 1988 campaign that increased minimum wages for some 60,000 New York City homecare workers by nearly 42 percent—a breakthrough that transformed the lives of low-wage healthcare workers. In 1985, Paterson played a key role in securing financial aid from District 1199 to stabilize North General Hospital in Harlem amid fiscal challenges, demonstrating his ability to leverage union resources for community benefit. His gentle demeanor belied his formidable negotiating skills; as 1199SEIU General Counsel Dan Ratner recalled, “The members were just in awe of him. He was enormously respected by the bosses as well. People would listen to what he had to say.”

Paterson’s labor representation provided crucial political capital for the Gang of Four, forging connections with union leaders like Bill Lynch NYC political strategist and rumpled genius, who had risen through AFSCME District Council 1701 to become Director of Legislation and Political Action before launching his political career. Labor unions formed the backbone of New York’s Democratic coalition, supplying votes, campaign funds, and organizational muscle. Paterson’s trusted relationships with over 40 unions—including the United Federation of Teachers, Transport Workers Union, and SEIU 1199—gave the Gang of Four direct access to the endorsements and mobilization networks essential for electoral victories, while Lynch’s parallel path from union organizer to political strategist exemplified the labor-to-politics pipeline that powered Black political advancement in New York.

Political Career & Historic Firsts

Paterson’s political career was marked by pioneering achievements and strategic coalition-building. In 1956, he formed a law partnership with three other young African American attorneys including David Dinkins, establishing the foundation for what would become the Gang of Four’s political dominance. Elected to the New York State Senate in 1965 representing Harlem and the Upper West Side, Paterson served in the 176th, 177th, and 178th legislatures, championing progressive causes that often put him at odds with conservative elements of his own party. He played a key role in preventing Columbia University from building a gym in Morningside Park—a victory for community control that galvanized Harlem activism. Despite his Catholic faith, Paterson was an early supporter of liberalized abortion laws, demonstrating the independence that defined his political philosophy. He also advocated for special education reform, revision of the state’s divorce laws, and perhaps most controversially, the right of public employees to strike—a position that would shape his entire career in labor law. In 1970, Paterson made history as the Democratic nominee for Lieutenant Governor on Arthur Goldberg’s ticket, becoming the first African American nominated for statewide office by a major party in New York. During the primary, Paterson received 100,000 more votes than Goldberg himself, and Albany machine boss Daniel P. O’Connell famously quipped, “He’s the only white man on the ticket”—an acknowledgment of Paterson’s crossover appeal despite the era’s racial prejudices. Though the Goldberg/Paterson ticket lost to Republican incumbents Nelson Rockefeller and Malcolm Wilson, Paterson had broken a critical barrier. In 1972, Basil Paterson became the first elected African American Vice Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, cementing his influence at the national level.

Quiet Strategist & Government Negotiatior

Among the famous Harlem politicians and Harlem Gang of Four members, Paterson’s government service demonstrated his unique ability to navigate the intersection of labor, politics, and public administration. In 1978, newly elected Mayor Ed Koch appointed Paterson as Deputy Mayor for Labor Relations and Personnel—perhaps the most challenging post in city government at the time. New York City was still struggling to emerge from a devastating financial crisis that had brought it to the brink of bankruptcy just three years earlier, and wage contracts with police, fire, sanitation, and dozens of other municipal employees represented one of the city’s largest budget expenditures. Paterson was charged with the unenviable task of meeting with powerful municipal union leaders—many of whom he had represented or worked with as allies—and asking for wage concessions to save the city from fiscal collapse. His credibility with labor, combined with his negotiating acumen, made him the only person who could have successfully navigated these treacherous waters.

In 1979, Governor Hugh Carey appointed Paterson as New York Secretary of State, making him the first African American to hold that position. He served with distinction until 1983, overseeing elections, licensing, and state records management. In 1985, as Koch prepared to seek a third term, speculation swirled that Paterson might run for mayor himself—polls showed him as a formidable potential candidate. After Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson was the second of the Harlem Gang of Four members who was in a position to become the first Black mayor of New York. However, Paterson declined, citing “pressing family problems,” a decision that surprised many political observers given his accumulated power and influence. Later, from 1989 to 1995, he served as a commissioner of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, where he oversaw critical infrastructure reforms. Throughout his career, Paterson remained the Gang of Four’s quiet strategist—less visible than Percy Sutton, less flamboyant than Charlie Rangel, less prominent than David Dinkins, but arguably the most skilled political operator of them all.

Legacy & Father-Son Political Dynasty

Basil Paterson’s greatest pride and most complex legacy came through his son, David Paterson, who became New York’s 55th Governor in 2008—the state’s first African American governor and first legally blind governor. When David contracted an infection as a child that left him legally blind, Basil and his wife Portia refused to let disability define their son’s future. They moved the family to a suburb where David could attend mainstream classes, aggressively pursuing normalcy and high expectations. Percy Sutton later encouraged David to run for the State Senate after the death of incumbent Leon Bogues in 1985—for the same seat Basil had held two decades earlier. David rose to become Senate minority leader from 2003 to 2006, then was elected Lieutenant Governor on Eliot Spitzer’s ticket in 2006. When Spitzer resigned in March 2008 following a prostitution scandal, David succeeded to the governorship. Basil was present at his son’s swearing-in and was recognized during the inaugural speech—a poignant moment for the Harlem Gang of Four members.

However, the father-son dynamic created delicate ethical challenges. Basil, still active as co-chair of Meyer, Suozzi’s labor practice and representing powerful unions like the United Federation of Teachers and SEIU 1199, had to maintain strict separation from his son’s political decisions. “If anybody thinks that I will make a call to my son on behalf of someone,” Basil declared publicly, “I can’t do that.” Despite this distance, Basil became David’s closest confidant as the new governor became entangled in controversies, including domestic abuse charges against a senior aide and perjury accusations in an ethics case involving Yankees tickets. Watching his son’s troubled tenure was painful for Basil, who had always been ambivalent about David entering politics due to his blindness. When David decided not to run for re-election in 2010, it marked the end of the Paterson political dynasty.

Basil Paterson died on April 16, 2014, at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, just days before his 88th birthday. At his death, The New York Times described him as “one of the old-guard Democratic leaders who for decades dominated politics in Harlem and influenced black political power in New York City and the state into the 21st century.” In 2020, David honored his father’s memory by publishing a biography titled “Black, Blind, & In Charge: A Story of Visionary Leadership and Overcoming Adversity,” ensuring that Basil Paterson’s quiet but profound impact on New York politics would not be forgotten. In 2013, 1199SEIU established The Basil Paterson Scholarship Fund for the Union’s homecare workers—a fitting tribute to a man who spent his life fighting for working people’s dignity and rights.

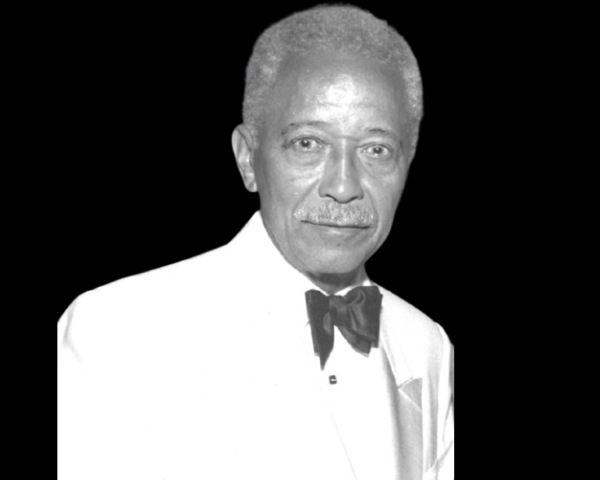

David Dinkins Mayor of New York City: The Elegant Face of Black Political Power

The election of David Dinkins as the first Black mayor of New York in 1989 represented the culmination of the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy developed over decades.. This historic victory demonstrated how systematic coalition-building could overcome seemingly insurmountable political obstacles.

While it was assumed that Percy Sutton or Basil Paterson would become the first Black mayors of New York City, David Dinkins was the ultimate beneficiary of the Harlem gang of Four political strategy and the only one of the Harlem Gang of Four members to fulfill the alliance’s highest ambition by becoming New York City’s first Black mayor. Dinkins brought a different profile than his three partners: he was soft-spoken, cerebral, dignified, and unthreatening to white voters who might be skeptical of Black political leadership.

Who was Mayor before Dinkins?

Ed Koch served as New York City’s mayor before David Dinkins, holding office from 1978 to 1989. Koch’s defeat in the 1989 Democratic primary marked a turning point in New York politics, as the Harlem Gang of Four’s coalition strategy successfully challenged the incumbent mayor.

Before his mayoral run, Dinkins served as Manhattan Borough President, a position that gave him citywide visibility and demonstrated his competence in municipal governance. This was the same position previously held by Percy Sutton, one of the most famous Harlem politicians and the key one of the Harlem Gang of Four members whom everyone expected would become the first black mayor of New York His calm demeanor and careful coalition-building made him the ideal candidate to lead a multiracial coalition to victory.

Dinkins was also deeply connected to Harlem’s civic and fraternal organizations. As a member of the Carver Democratic Club and numerous community groups, he had roots in the grassroots organizing that would be essential for mobilizing Black voters.

Within the Gang of Four alliance, Dinkins emerged as the member best positioned to win citywide office—his calm demeanor and careful coalition-building made him an ideal candidate to lead a multiracial coalition to victory.

Early life, military service & legal career

David Norman Dinkins was born on July 10, 1927, in Trenton, New Jersey, to Sarah “Sally” Lucy Dinkins, a domestic worker, and William Harvey Dinkins Jr., a barber and real estate agent. His parents separated when he was six, after which he lived briefly with his mother in Harlem before returning to Trenton to be raised by his father. Growing up during the Great Depression, Dinkins attended Trenton Central High School and graduated in 1945. Upon graduation, he attempted to enlist in the United States Marine Corps but was repeatedly told that racial quotas had been filled. After traveling throughout the Northeastern United States, Dinkins finally found a recruiting station willing to accept him. World War II ended before he finished boot camp, but Dinkins served from July 1945 through August 1946, attaining the rank of private first class. He was among the more than 20,000 Montford Point Marines, the first African Americans to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps—a barrier-breaking achievement for which he later received the Congressional Gold Medal from the United States Senate and House of Representatives.

After his military service, Dinkins attended Howard University on the G.I. Bill, graduating cum laude in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. At Howard, he met his future wife, Joyce Burrows, whose father, Daniel L. Burrows, was among the first Black Democratic district leaders in Manhattan and one of the first Black members of Tammany Hall. Daniel Burrows would prove instrumental in guiding his son-in-law toward a career in law and politics. Dinkins married Joyce in August 1953, and they moved to Harlem where they eventually raised two children, David Jr. and Donna. While working to support his young family, Dinkins attended Brooklyn Law School from 1953 to 1956, earning his LL.B. degree. In 1956, he established a private law practice focusing on business and real estate, which he maintained until 1975. That same year, Dinkins partnered with Basil Paterson, Fritz Alexander, and two other young African American attorneys—a professional alliance that laid the foundation for what would become the Gang of Four.

Political Rise, Tax Crisis & Resilience

Dinkins began his rise through Harlem’s Democratic Party machinery under the mentorship of another one of the famous harlem politicians, J. Raymond Jones, the legendary “Harlem Fox” known for his strategic prowess in Black political organizing. Through the Carver Democratic Club, Dinkins started as a district captain, conducting voter registration drives and grassroots mobilization—essential work during an era when African Americans faced systemic barriers to political influence. This apprenticeship honed his organizational skills and connected him to emerging Black political figures including Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and Charles Rangel—the other three of the eventual Harlem Gang of Four members. In 1966, Dinkins briefly represented the 78th District in the New York State Assembly, where he helped create the Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge (SEEK) program, which provides low-income students with grants and assistance to succeed in higher education. From 1972 to 1973, he served as president of the New York City Board of Elections, significantly expanding voter registration rolls.

In late 1973, Mayor-elect Abraham D. Beame nominated Dinkins to become New York City’s first Black deputy mayor—a historic appointment that would have brought tremendous recognition to both Dinkins and Harlem’s political power. However, the appointment unraveled when the Beame administration discovered that Dinkins had obtained extensions for, but not paid, federal, state, and city personal income taxes for four years. Dinkins explained that he had legally “rolled over” the extensions and believed he had informed the government of his intention to pay “in the fullness of time,” but the failure to actually pay was sufficient for Beame to withdraw the offer. Dinkins later described these events in a chapter of his autobiography entitled “From Sugar to Shit in a New York Minute”—one of the only times he lapsed into vulgarity. While no illegality was involved, the incident was deeply humiliating and threatened to derail his political career.

Down but not out, Dinkins demonstrated remarkable resilience. With support from allies including Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton and City Council President Paul O’Dwyer, Dinkins was appointed City Clerk in 1975—a patronage position responsible for marriage licenses and municipal records. Though unglamorous, Dinkins held this post for a decade, using it as a platform for political networking. Almost every night, he attended dinners, fundraisers, and community events, steadily rebuilding his reputation and making contacts throughout the city. He ran unsuccessfully for Manhattan Borough President in 1977 and 1981, but finally won the seat in 1985 on his third attempt. Supporters used to joke with him: “What do you do?” to which Dinkins would reply, “I run for borough president.”

Manhattan Borough President & Historic Mayoral Victory

As Manhattan Borough President from 1986 to 1989, David Dinkins cultivated a reputation for moderation and coalition-building amid widespread dissatisfaction with Mayor Ed Koch’s administration. Koch faced accusations of exacerbating racial divisions through his handling of incidents like the 1986 Howard Beach attack (where a Black man was killed by a white mob) and the 1989 Bensonhurst killing of 16-year-old Yusuf Hawkins (a Black teenager chased and murdered by a white mob in Brooklyn). Koch’s administration was also damaged by corruption scandals tied to the decline of Brooklyn Democratic Party chairman Meade Esposito’s Mafia-influenced patronage network. As borough president, Dinkins enhanced his reputation as a champion of the poor, the homeless, and people with AIDS, positioning himself as a reform-minded alternative who could bring racial healing to a deeply divided city.

In the 1989 Democratic mayoral primary, Dinkins shocked political observers by defeating three-term incumbent Koch, receiving 51% of the vote. His campaign manager was the now nationally recognized Bill Lynch NYC political strategist., a former AFSCME union organizer who would become one of Dinkins’ most trusted advisers and first deputy mayors. Dinkins then faced Republican nominee Rudy Giuliani, a former U.S. Attorney, in the general election. The campaign was tense, with both candidates forced to address the city’s escalating racial tensions. Dinkins campaigned throughout all five boroughs, assembling a multiracial coalition that included African Americans, Latinos, white liberals, and labor unions—particularly the 1199SEIU healthcare workers’ union, which mobilized more than 2,000 members for his campaign even as the union was engaged in its own crucial contract battle. On November 7, 1989, Dinkins narrowly defeated Giuliani with 50.7% of the vote, becoming New York City’s 106th mayor and the first Black mayor of New York City.

Dinkins entered office on January 1, 1990, pledging racial healing and famously describing New York City’s demographic diversity as “not a melting pot, but a gorgeous mosaic.” The phrase captured his vision of a city where different communities could coexist while maintaining their distinct identities. However, Dinkins inherited an unprecedented crisis: a budget deficit that reached $1.8 billion (the result of the worst local recession since the Great Depression), a homicide rate that hit an all-time high of 2,245 murders in 1990, escalating crack epidemic, and a homeless population that had reached crisis levels. As one colleague noted, Dinkins’ deliberate, courtly manner—his use of phrases like “bless your heart” and “pray tell”—was atypical of New York’s rough-and-tumble politics, but his measured approach masked a determined pragmatism and willingness to make difficult decisions.

Mayoral Achievements & Crown Heights Crisis

Despite inheriting a city in crisis, Dinkins achieved a number of significant accomplishments during his single term. Working with City Council Speaker Peter Vallone Sr., Dinkins persuaded the state legislature to enact the “Safe Streets, Safe City: Cops and Kids” program—the most ambitious restructuring of the NYPD in the city’s history. The program raised taxes to hire approximately 6,000 new police officers (increasing the force to over 38,000 officers and creating the largest street patrol force in the city’s history), while also dedicating resources to after-school programs and Beacon community centers designed to provide teenagers with alternatives to street life. The comprehensive approach combined law enforcement with youth development, and crime rates—including the murder rate—began declining during Dinkins’ last three years in office, laying the groundwork for the dramatic crime reductions that continued under his successor. Dinkins also reformed the Civilian Complaint Review Board, making it an independent civilian-run agency to investigate police misconduct.

Beyond public safety, Dinkins negotiated a 99-year lease with the United States Tennis Association to keep the U.S. Open in New York City—a deal that generates more annual revenue for the city than the Yankees, Mets, Knicks, and Rangers combined (Mayor Michael Bloomberg later called it “the only good athletic sports stadium deal, not just in New York, but in the country”). Dinkins initiated the revitalization of Times Square, persuading The Walt Disney Company to rehabilitate the old New Amsterdam Theatre on 42nd Street in a deal signed on the last day of his administration in December 1993. He continued housing rehabilitation initiatives begun under Koch, and more housing was rehabilitated during Dinkins’ single term than in Giuliani’s two terms. With support from Governor Mario Cuomo, the city invested in supportive housing for mentally ill homeless people, reducing the shelter population to its lowest level in two decades. Dinkins also created cultural and economic initiatives that continue today: Fashion Week, Restaurant Week, and Broadway on Broadway.

However, Dinkins’ mayoralty was severely damaged by the Crown Heights riots in August 1991. The unrest began when a car in the motorcade of Chabad Lubavitch Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson accidentally struck and killed seven-year-old Gavin Cato, a child of Guyanese immigrants. Hours later, amid outrage over Cato’s death, a group of Black men murdered Yankel Rosenbaum, a Lubavitch rabbinical student from Australia. For three days, rioters attacked Orthodox Jews, looted businesses, and threw rocks and bottles—including at Dinkins himself when he visited the neighborhood. The mayor had to take shelter in the Cato household to avoid serious injury.

Dinkins was heavily criticized for not deploying sufficient police force quickly enough to quell the violence. A July 1993 state report commissioned by Governor Cuomo faulted Dinkins for relying “uncritically” on police assessments that underestimated the severity of the riots. Dinkins maintained that he was not fully aware of how serious the violence was until the third day, when he personally became a target. The mayor was deeply offended when political opponents—including Rudy Giuliani, Ed Koch, and others—began describing the riots as a “pogrom,” a term that implied state-sanctioned violence and suggested Dinkins personally was antisemitic. “There is not a single shred of evidence that I held the NYPD back—and there never will be,” Dinkins later stated. “And every time this utterly false charge is repeated, the social fabric of our city tears just a little bit more.” In his 2013 memoir, Dinkins attributed the criticism to racism: “I think it was just racism, pure and simple.” The Crown Heights riots became a central issue in the 1993 mayoral race, contributing significantly to Dinkins’ narrow defeat by Giuliani. In three Brooklyn Hasidic neighborhoods—Crown Heights, Williamsburg, and Borough Park—approximately 97% of voters backed Giuliani.

Post-Mayoral Career, Teaching Legacy & Lasting Impact

After losing his reelection bid in November 1993, Dinkins joined Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) in spring 1994 as a Professor in the Practice of Public Policy, at the invitation of University President George Rupp and SIPA Dean John Ruggie. Dinkins was 66 years old and, as he joked to his wife Joyce, would soon be “unemployed” and “losing their public housing” (Gracie Mansion). He would remain a beloved faculty member for nearly 27 years, teaching courses including “Critical Issues in Urban Public Policy” and “Practical Problems in Urban Politics.” Dinkins encouraged all his students to engage in public service, whether in government or through nonprofit organizations: “I don’t care if it’s the Red Cross or the NAACP—do something. I think there’s no better laboratory than the City of New York for the things that we teach here.”

Beginning in 1995, Dinkins oversaw and hosted the annual David N. Dinkins Leadership & Public Policy Forum, which welcomed national figures including Vice President Al Gore, Senator Hillary Clinton, and civil rights icon Congressman John Lewis to discuss issues like criminal justice reform, education, race, immigration, and voting rights. In 2002, Columbia launched the David N. Dinkins Archives and Oral History Project, and in 2015, SIPA established the David N. Dinkins Professorship in the Practice of Urban & Public Affairs—with former Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter as the inaugural appointee. That same year, Mayor Bill de Blasio (who had worked in the Dinkins administration and met his wife Chirlane McCray there) renamed Manhattan’s Municipal Building the David N. Dinkins Municipal Building. Dinkins stepped down from teaching in 2017 after celebrating his 90th birthday but continued to host the annual forum and serve on numerous boards.

Unlike many former elected officials, Dinkins did not become a lobbyist or corporate rainmaker. Instead, his post-mayoral calendar was filled with appearances at homeless shelters, soup kitchens, nursing homes, schools, and cause-related fundraisers. He served on boards including the United States Tennis Association, Children’s Health Fund, Association to Benefit Children, Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, Coalition for the Homeless, Jazz Foundation of America, and Posse Foundation. He was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the National Advisory Board of the International African American Museum. From 1994 to 2014, Dinkins hosted the radio program “Dialogue with Dinkins” on WLIB, the first Percy Sutton owned radio station that was so important to the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy. In 2013, he published his memoir, “A Mayor’s Life: Governing New York’s Gorgeous Mosaic,” written with Peter Knobler, to “set the record straight” about his administration.

David Dinkins, the first Black mayor of New York, inspired a generation of Black political leaders. Among those who worked in his administration were future New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, presidential advisor Patrick Gaspard (who became executive vice president of 1199SEIU, later President Obama’s political director, and subsequently United States Ambassador to South Africa ), and Karine Jean-Pierre (who became White House Press Secretary under President Biden). New York City Council Majority Leader Laurie Cumbo credited Dinkins with opening doors: “His campaign inspired and ushered in the new wave of Black elected leaders, which then opened up opportunities for all people to know that they can also lead.” David Dinkins died at his home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side on November 23, 2020, at age 93—less than two months after his wife Joyce’s death. Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg observed: “All the mayors who followed Dinkins stood on his shoulders and built on his legacy.” President Obama called him a “true hero” whose dedication to public service “made the rise of countless young African Americans possible.”

David Dinkins Mayor – Key Achievements Highlighted:

Military Service:

- Montford Point Marine (1945-1946) – first African Americans in U.S. Marine Corps

- Congressional Gold Medal recipient

Education:

- Howard University, B.S. Mathematics, cum laude (1950)

- Brooklyn Law School, LL.B. (1956)

Political Career Progression:

- NY State Assembly (1966)

- NYC Board of Elections President (1972-1973)

- NYC City Clerk (1975-1985)

- Manhattan Borough President (1985-1989)

- NYC Mayor (1990-1993)

Major Mayoral Accomplishments:

- Safe Streets, Safe City: Hired 6,000+ police officers, largest NYPD expansion in history

- Crime reduction: Murders declined 13% during tenure (2,245 in 1990 → 1,946 in 1993)

- Reformed Civilian Complaint Review Board to independent civilian agency

- U.S. Open 99-year lease deal (more revenue than Yankees/Mets/Knicks/Rangers combined)

- Times Square revitalization (Disney New Amsterdam Theatre deal)

- Housing rehabilitation: More units rehabilitated than Giuliani’s two terms

- Homeless services: Reduced shelter population to 20-year low

- Created Fashion Week, Restaurant Week, Broadway on Broadway

- Beacon community centers for youth

Post-Mayoral Legacy:

- Columbia SIPA Professor (1994-2017, 27 years)

- David N. Dinkins Leadership & Public Policy Forum (1995-2020)

- David N. Dinkins Municipal Building named 2015

- David N. Dinkins Professorship established at SIPA (2015)

- “Dialogue with Dinkins” radio show (1994-2014)

- Memoir: “A Mayor’s Life: Governing New York’s Gorgeous Mosaic” (2013)

- Mentored Bill de Blasio, Patrick Gaspard, Karine Jean-Pierre, and generation of Black leaders

Personal:

- Married Joyce Burrows (1953-2020)

- Two children: David Jr. and Donna

- Member: Alpha Phi Alpha, Sigma Pi Phi, Master Mason

- Died November 23, 2020 (age 93)

When was David Dinkins Mayor?

David Dinkins served as New York City’s mayor from 1990 to 1993, becoming the city’s first Black mayor. Elected in 1989 through the coalition-building efforts of the Harlem Gang of Four, Dinkins defeated incumbent Ed Koch in the Democratic primary and Republican Rudy Giuliani in the general election.

The Council of Black Elected Democrats (COBED): Institutionalizing Black Political Power

The Harlem Gang of Four members understood that Black political power required more than individual elected officials—it required institutional coordination. This insight led to the formation of the Council of Black Elected Democrats (COBED), a regular gathering of Black elected officials in New York City designed to set policy priorities and coordinate electoral strategy.

COBED was groundbreaking. While its decisions were not binding, the effort at consensus gave weight to the concerns of Black New Yorkers and created a unified voice that city and state officials could not ignore. The Gang of Four used COBED to amplify their influence, coordinate endorsements, and mobilize Black voters around shared priorities.

During the 1980s, COBED meetings brought together Congressmen Rangel, Major Owens, and Ed Towns; State Senators; City Council members; and other Black elected officials from Harlem, Brooklyn, Queens, and The Bronx. These gatherings became the central nervous system of Black politics in New York City. But the appearance of unity masked a fundamental tension: Harlem versus Brooklyn. While the Harlem Gang of Four dominated headlines and wielded influence from their Manhattan power base, Central Brooklyn’s Black political class represented something the Gang of Four could not claim—sheer numbers. Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and East New York formed the largest concentration of Black residents in New York City, dwarfing Harlem’s population. Brooklyn politicians like Congressmen Major Owens and Ed Towns, along with Assemblyman Al Vann and a cohort of ambitious state legislators and community leaders, increasingly questioned why political strategy and resources flowed through Harlem when demographic power resided in Brooklyn. This rivalry would eventually produce the Coalition for Community Empowerment, founded by Al Vann and other Brooklyn leaders, a formal organization that challenged the informal Gang of Four’s model and charted its own path to Black political power.

Political strategist Basil Smikle Jr. wrote about COBED’s significance:

Though largely forgotten today, COBED was a regular gathering of Black elected officials in New York City, an effort to set policy priorities and coordinate electoral strategy. Its decisions were not binding, but the effort at consensus gave weight to the concerns of Black New Yorkers.

The Gang of Four’s leadership of COBED demonstrated their understanding that power required infrastructure—not just charisma, not just protest, but organized, strategic coordination across institutions and electoral districts. Through an alliance with Bill Lynch NYC political operative and Bill Banks, a Brooklyn based NYC political operative (with Harlem roots and ties to the Harlem Gang of Four, Brooklyn Congressman Ed Towns , and other Black elected officials in The Bronx and Queens), COBED, and some members of CCE members participated in launching Countdown 88 at the New York City voter registration and mobilization campaign‘s kickoff that ,helped set the stage for the emergence of David Dinkins as the first Black mayor of New York.

Strategic Infrastructure: Building the Machine

The Harlem Gang of Four political strategy and genius lay not in individual brilliance but in their systematic approach to building political infrastructure. They understood that sustainable Black political power required:

1. Electoral Infrastructure

The Gang of Four helped to initiate or invested in voter registration drives, get-out-the-vote operations, and precinct organization. They cultivated relationships with block associations, church networks, and civic groups that could mobilize voters when needed.

2. Media Access

Through Percy Sutton’s Inner City Broadcasting, the Gang of Four had direct access to Black voters through WLIB and WBLS. These stations became essential tools for political communication, candidate endorsements, and voter mobilization.

3. Economic Leverage

The Gang of Four understood that political power without economic power was fragile. They advocated for minority contracting, supported Black business development, and used their positions to channel resources to Harlem and other Black communities.

4. Coalition Building

While rooted in Harlem, the Gang of Four built coalitions with Latino leaders, labor unions, progressive whites, and other communities of color. They understood that Black political power in New York City required multiracial alliances.

5. Institutional Relationships

The Harlem Gang of Four political strategy of coalition building was formidable, weaving together religious networks that could amplify their political work, civic institutions, community-based organizations, and labor unions into a unified force. Bill Lynch, the NYC political operative who became the Gang of Four’s chief strategist, cultivated relationships with civic institutions like the Community Service Society and labor unions including AFSCME District Council 37 and SEIU 1199. Both Lynch and Basil Paterson emerged as key labor strategists—Lynch from his background as Director of Legislation and Political Action for AFSCME District Council 1701, and Paterson from his decades representing over 40 unions as a labor attorney. This labor-political pipeline gave the Gang of Four direct access to the endorsements, campaign funds, and mobilization networks that formed the backbone of New York’s Democratic coalition.

The Countdown 88 Connection: Translating Strategy into Infrastructure

Who was Bill Lynch in NYC politics?

Bill Lynch NYC political strategist was a legendary NYC political organizer known as “The Rumpled Genius” who managed David Dinkins’ historic 1989 mayoral campaign. Lynch was a trusted operative for the Harlem Gang of Four members. Lynch called on David R. Jones, president and CEO of the Community Service Sociaty to sponsor and recruited Selwyn Carter to serve as director of Countdown 88, the massive non-partisan voter registration and mobilization drive at the urging of the Harlem Gang of Four. Lynch later became Deputy Mayor under Dinkins. His coalition-building skills and strategic acumen made him one of the most respected political operatives in New York City history.

The Harlem Gang of Four’s most consequential strategic move in the late 1980s was to initiate the building of a massive voter registration and mobilization campaign and infrastructure ahead of the 1988 presidential election and the 1989 mayoral race. This infrastructure proved decisive in electing the first Black mayor of New York the following year.

The idea for Countdown 88 originated out of the Gang of Four inner circle. Bill Lynch NYC trusted strategist of the Gang of Four, approached community organizer Selwyn Carter with a proposal: build a citywide, nonpartisan voter registration campaign that could register hundreds of thousands of new Black and Latino voters in New York City.

Lynch turned to the Community Service Society of New York (CSS), led by David R. Jones, to sponsor the initiative and brought to the table the key major NYC labor groups as partners. CSS provided institutional credibility, nonprofit status, and organizational infrastructure. But the strategic vision came from the Gang of Four.

Countdown 88 was launched in December 1987 with a carefully staged kickoff that brought together COBED members, labor leaders, clergy, and community activists. The campaign is credited with registering tens of thousands of new voters across New York City, with a particular focus on Black and Latino communities in Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Queens.

The infrastructure built by the nonpartisan Countdown 88—the volunteer networks, the precinct maps, the voter files, the relationships with churches and unions—proved pivotal in mobilizing Black and Brown voters in New York City and was foundational in David Dinkins’s 1989 mayoral campaign victory. When Dinkins announced his candidacy, he inherited a mobilized electorate and an organized infrastructure that the Gang of Four had strategically nurtured.

Learn more about Countdown 88’s voter registration infrastructure

The Jesse Jackson Partnership: National Platform, Local Infrastructure

The Harlem Gang of Four’s relationship with Jesse Jackson was symbiotic. Jackson needed New York City to demonstrate that a Black candidate could win in the nation’s largest, most diverse city. The Gang of Four needed Jackson’s national platform and grassroots energy to mobilize voters who would later support David Dinkins.

The 1988 Jackson Campaign in NYC

When Jesse Jackson launched his 1988 presidential campaign, the Gang of Four saw an opportunity. Jackson’s campaign brought national media attention, celebrity endorsements, and grassroots enthusiasm that could be harnessed for local organizing.

The Gang of Four’s influence extended beyond New York City through Percy Sutton’s media empire. As founder and president of Inner City Broadcasting Corporation, Sutton owned radio stations in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit, and San Antonio—a strategic network of Black-owned stations reaching key urban markets across the country. This media infrastructure proved invaluable to Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign. Sutton, who had been talking about electing a Black president since 1972, served as an advisor to Jackson’s campaign and, as Jackson himself acknowledged, was “influential in getting his 1984 campaign going.” Sutton’s mentorship and his radio network’s reach gave Jackson access to Black communities nationwide. The stations provided airtime for Jackson’s message, mobilized voters, and helped build the grassroots energy that powered his surprising third-place finish in the Democratic primaries. Jackson’s campaign aligned with the Harlem Gang of Four’s political strategy of demonstrating Black political power through coalition-building and voter mobilization. The Gang of Four’s work with Bill Lynch to build infrastructure through Countdown 88 provided the organizational foundation that helped to energize both Jackson’s 1988 New York primary victory and Dinkins’s 1989 mayoral campaign.

Jackson’s stunning victory in the New York City Democratic primary in April 1988 demonstrated that a multiracial, Black-led coalition could win in New York. This victory was the proof-of-concept that made David Dinkins’s mayoral campaign viable.

The partisan networks, volunteers, and energy generated by Jackson’s campaign were channeled directly into the Dinkins campaign. The non-partisan mobilization networs and infrastructure from Countdown 88 rolled right into Countdown 89—the successor to Countdown 88—which focused specifically on the mayoral election. The Gang of Four had successfully used Jackson’s national campaign as a vehicle to build local infrastructure.

Explore Jesse Jackson’s 1988 presidential campaign and its impact

The Dinkins Campaign: The Gang of Four’s Masterpiece

David Dinkins’s 1989 mayoral campaign was the culmination of decades of strategic planning by the Harlem Gang of Four. Every element of the campaign reflected their influence:

The Infrastructure

Countdown 88 and Countdown 89 had registered and mobilized hundreds of thousands of voters. Behind the scenes, the Gang of Four had a major hand in launching and nurturing this network that would help turn out Black voters at historic levels.

The Coalition

Dinkins ran a multiracial campaign that brought together Black voters, Latino communities, liberal whites, labor unions, and progressive activists. This coalition reflected the Gang of Four’s reach and long-standing commitment to building bridges across communities.

The Strategy

Bill Lynch NYC, the Gang of Four’s chief strategist, served as Dinkins’s campaign manager. Lynch’s careful navigation of New York’s racial politics, his coalition-building skills, and his deep relationships with both labor and community leaders were essential to Dinkins’s narrow victory.

The Symbolism

Dinkins’s campaign represented the validation of the Gang of Four’s decades-long investment in Black political infrastructure. When Dinkins took the oath of office in January 1990, he became the living embodiment of the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy.

Legacy and Lessons: What the Gang of Four Teaches Us

The Harlem Gang of Four’s legacy extends far beyond David Dinkins’s mayoral tenure. Their model of strategic, infrastructure-focused Black political power offers enduring lessons:

1. Coalition Over Competition

The Gang of Four succeeded because they prioritized collective power over individual ambition. They coordinated rather than competed, shared resources rather than hoarded them, and understood that their individual success depended on the group’s strength.

2. Infrastructure Over Charisma

While all four members were talented and charismatic, they didn’t rely on personality alone. They often worked behind the scenes to help build institutions, cultivate relationships, invest in media, and create organizational infrastructure that outlasted individual campaigns.

3. Long-Term Vision Over Short-Term Wins

The Gang of Four played the long game. They invested in voter registration years before the Dinkins campaign. The Gang of Four helped build institutional infrastructure like the Council of Black Elected Democrats (COBED), with Dinkins serving as a founding member. They understood that sustainable power required patient, strategic work, sometimes, behind the scenes work.

4. Economic Power Complements Political Power

Percy Sutton’s investment in Black media and business development reflected the Gang of Four’s understanding that political power without economic leverage is fragile. They advocated for minority contracting, supported Black entrepreneurship, and used their positions to channel resources to the community.

5. Multiracial Coalitions Are Essential

While rooted in Harlem’s Black community, the Gang of Four built coalitions across racial and ethnic lines. They understood that in a diverse city like New York, Black political power required alliances with Latinos, labor unions, progressive whites, and other communities of color.

The Gang of Four’s Influence on Modern Black Politics

The Harlem Gang of Four’s strategic model influenced Black political organizing far beyond New York City:

Electoral Infrastructure

Their investment in voter registration, precinct organization, and get-out-the-vote operations became a model for Black political campaigns nationwide.

Institutional Coordination

COBED was part of a national movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s that saw Black elected officials organizing in cities across the country—from Chicago to Philadelphia to Atlanta—to coordinate strategy and build collective political power.

Coalition Building

The multiracial coalition strategy that elected Dinkins—building on Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition model—demonstrated the viability of bringing together African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, white liberals, labor unions, and the LGBT community to win citywide office in various cities actoss the country.

Media and Communication

Percy Sutton’s recognition that Black political power required Black-owned media presaged the importance of digital media and communication infrastructure in contemporary politics.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Harlem Gang of Four

Who were the Harlem Gang of Four? The Harlem Gang of Four were Charles B. Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Paterson, and David Dinkins—four Black political leaders who formed a strategic alliance in Harlem that dominated New York City politics from the 1970s through the 1990s and built the infrastructure that elected David Dinkins as NYC’s first Black mayor.

What was the Harlem Gang of Four political strategy? The Harlem Gang of Four political strategy focused on building institutional infrastructure including voter registration campaigns like Countdown 88, coordinating Black elected officials through COBED, controlling Black media through Inner City Broadcasting, and forming multiracial coalitions to maximize Black political power in New York City.

How did the Harlem Gang of Four help elect David Dinkins? The Harlem Gang of Four orchestrated Countdown 88 and Countdown 89 voter registration campaigns that played a major role in registering hundreds of thousands of new voters, built the organizational infrastructure, formed the multiracial coalition, and provided strategic leadership through Bill Lynch that culminated in David Dinkins’s 1989 mayoral victory.

What was COBED and how did the Gang of Four use it? COBED (Council of Black Elected Democrats) was a coordinating body of Black elected officials in New York City that the Gang of Four and others used to set policy priorities, coordinate electoral strategy, and create a unified voice for Black political concerns in the city and state.

How did the Harlem Gang of Four influence Jesse Jackson’s 1988 campaign? The Harlem Gang of Four facilitated Jesse Jackson’s 1988 NYC presidential primary victory by connecting his campaign with NYC community leaders and ensuring that the voter registration and mobilization generated by the non-partisan Countdown 88 campaign infrastructure impacted Jackson’s voter mobilization efforts, while also using Jackson’s campaign energy to build infrastructure for David Dinkins’s mayoral run.

What is the legacy of the Harlem Gang of Four today? The Harlem Gang of Four legacy includes the institutional model of coordinating Black political power, the emphasis on building electoral infrastructure over relying on charisma alone, the importance of multiracial coalitions, and the recognition that political power requires economic leverage—principles that continue to influence Black political organizing nationwide.

The Enduring Relevance of Strategic Black Political Power

As American politics becomes increasingly diverse and competitive, the Harlem Gang of Four’s model of strategic, infrastructure-focused Black political organizing remains deeply relevant. Their understanding that power requires patience, coordination, and long-term investment offers a counterpoint to the celebrity-focused, social media-driven politics of today.

The Gang of Four built institutions that outlasted individual careers. They invested in relationships that created networks of mutual support. They understood that winning one election was less important than building the capacity to win many elections over time.

In an era when Black political power faces new challenges—from voter suppression and historic rollbacks to economic inequality to the fragmentation of media—the Gang of Four’s lessons endure: Build infrastructure. Coordinate strategy. Form coalitions. Play the long game. And never mistake individual achievement for collective power.

The Harlem Gang of Four didn’t just elect New York City’s first Black mayor. They created a blueprint for how marginalized communities can transform aspiration into political power—one voter, one precinct, one coalition at a time.

A documentary on the lives and impact of the Harlem Gang of Four is being created by Leah Natasha Thomas, chronicling the careers of Congressman Charles Rangel, former Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton, former Mayor David Dinkins, and former Secretary of State Basil Paterson.

Related Articles:

- Countdown 88: When NYC’s Majority Mobilized

- Jesse Jackson: Architect of Black Political and Economic Power

Published: [Date] Last Updated: [Date]