Frederick Douglass and Ulysses S. Grant on Reconciliation and Its Pitfalls – BillMoyers.com

This post first appeared in the Muster: How the Past Informs the Future blog of The Journal of the Civil War Era.

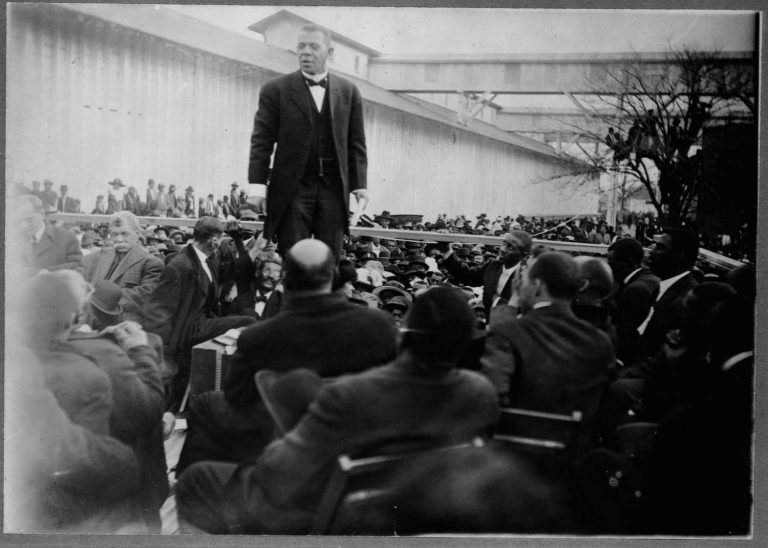

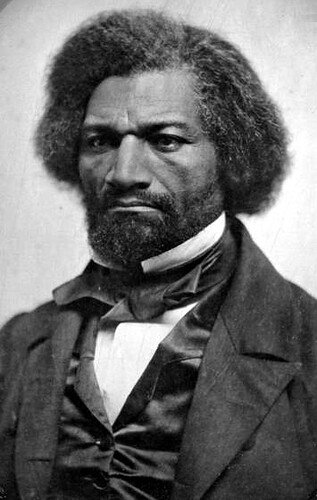

Speaking in New York City in 1878, Frederick Douglass had a warning for white northerners about how they remembered the Civil War. “Good, wise, and generous men at the North,” Douglass observed, “would have us forget and forgive, strew flowers alike and lovingly, on rebel and on loyal graves.”

A group of white veterans had invited Douglass to speak at a ceremony commemorating Decoration Day — the holiday, later known as Memorial Day, for remembrance of the Civil War’s Union dead. In the shadow of Abraham Lincoln’s statue in Union Square, Douglass invoked Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address as he tried to arrest the drift of northern opinion and national politics.

“There was a right side and a wrong side in the late war, which no sentiment ought to cause us to forget,” Douglass declared. “[W]hile to-day we should have malice toward none, and charity toward all, it is no part of our duty to confound right with wrong, or loyalty with treason.”1

Douglass’s words will resonate with many Americans today, after the divisive 2020 election and especially the trauma of the January 6 insurrection. We too hear invocations of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural and calls for healing, unity and reconciliation. At the same time, we hear worries that those appeals — sometimes made sincerely, but often cynically — will forestall a reckoning with the divisions and wrongs that landed us here.

The post-Civil War years teach us the perils of heeding calls for reconciliation while ignoring those for justice. It also provides us, in Douglass’s 1878 speech, a powerful example of how to combine them.

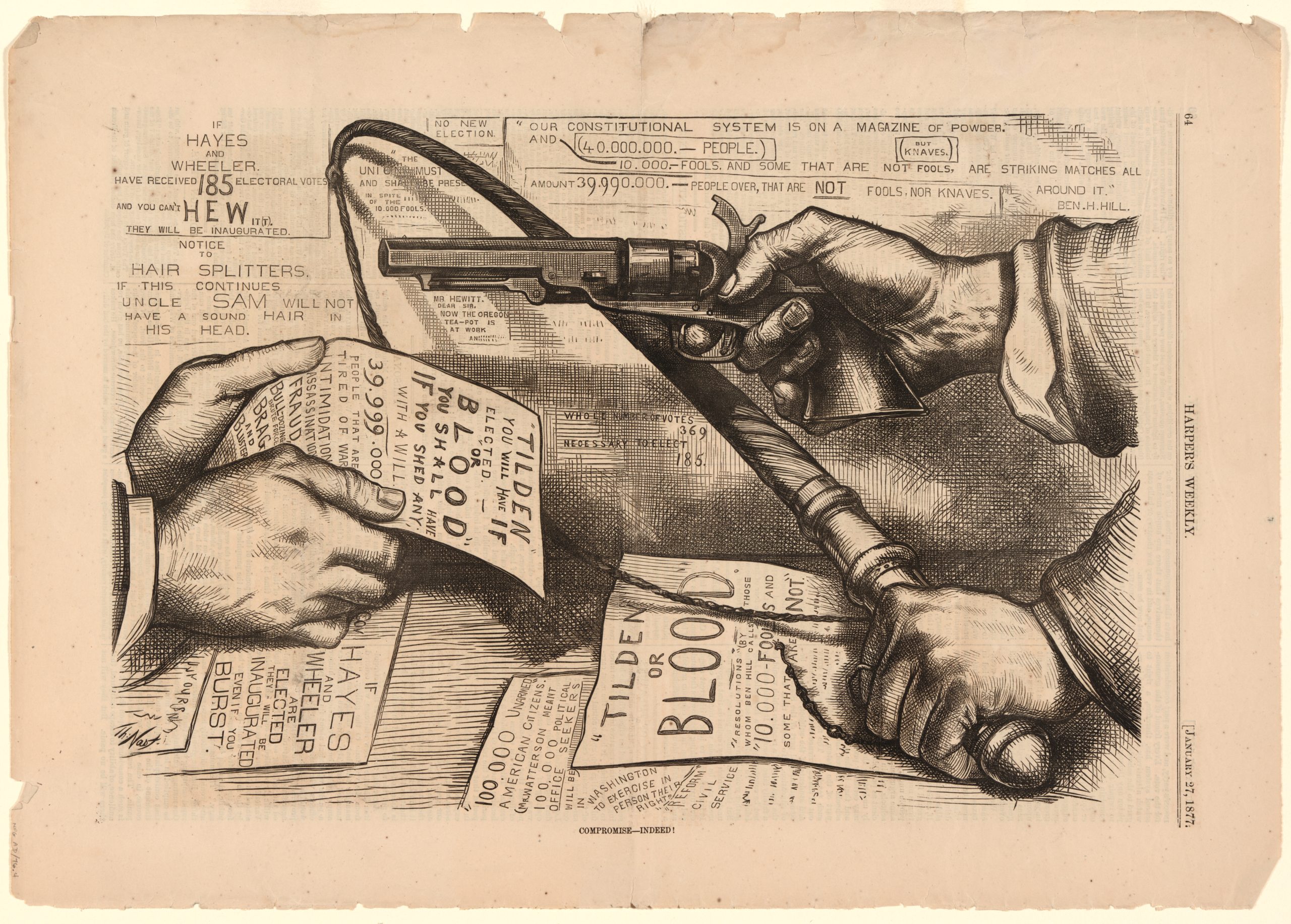

The backdrop for Douglass’s speech was another contested presidential election that has been in the news of late: the protracted 1876-77 electoral crisis. It ended with the installation of Rutherford B. Hayes as president and the ouster of the last Republican state governments in the South, amidst waves of terrorism and fraud. In Reconstruction’s twilight, Douglass struggled to recall white northerners to the Civil War’s emancipationist legacy of eradicating slavery and its traces in American life. But doing so brought the charge — shades of 2021 — that he was an agent of division and disunity.

“I am not here to fan the flame of sectional animosity, to revive old issues, or to stir up strife between races,” he declared, “but no candid man, looking at the political situation of the hour, can fail to see that we are still afflicted by the painful sequences both of slavery and of the late rebellion.”2

Douglass made his case not by rejecting reconciliation, but by echoing and recasting two of its most famous expressions from the Civil War era. One, noted above, came from the closing line of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural. Another is less well known today but was immediately familiar to Americans in 1878. “Let us have peace” was the closing line of Ulysses S. Grant’s letter accepting the 1868 Republican nomination for president and became a motto for his campaign. Douglass put it to his own use:

In the language of our greatest soldier, twice honored with the Presidency of the nation, “Let us have peace.” Yes, let us have peace, but let us have liberty, law, and justice first. Let us have the Constitution, with its 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, fairly interpreted, faithfully executed, and cheerfully obeyed in the fullness of their spirit and the completeness of their letter.

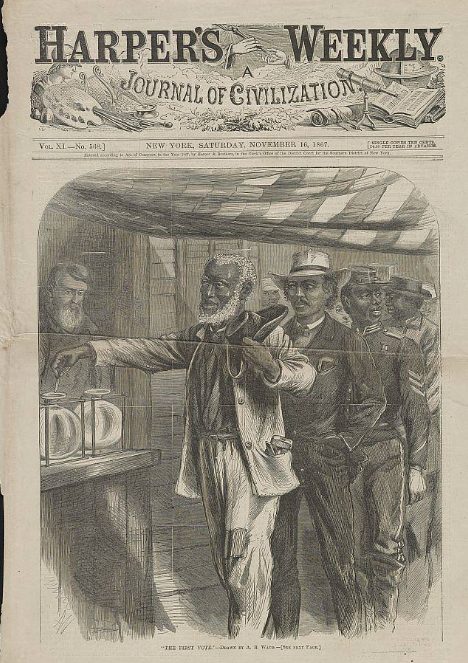

True reconciliation, for Douglass, required a clear-eyed reckoning with the causes of division and a firm commitment to remedy them. Both Lincoln and Grant had met that test. In the Second Inaugural, Lincoln meditated on the national sin of slavery as the cause of the war and pledged to pursue a “just, and lasting peace.” The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were the war’s settlement written into the Constitution, and Grant, as president, had used the U.S. Army to enforce them.3

Douglass’s vision of reconciliation was rooted in his Christian faith and found expression in his personal life as well as his politics. The abolitionist had attended the 1865 inauguration and immediately pronounced Lincoln’s address, with its reflections on God’s will and the meaning of the Civil War, a “sacred effort” — a phrase Douglass did not use lightly or loosely.

The year before Douglass’s New York City speech, his impulse towards charity and forgiveness led him to visit his former enslaver Thomas Auld, now elderly and bedridden on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Although some critics, as Douglass later acknowledged, viewed that meeting as a “weakening” of his “life-long testimony against slavery,” he had not forgotten the wrongs he suffered from one who “made property of my body and soul.” But with slavery ended and Auld “stepping into his grave,” Douglass wished to meet “upon equal ground” for “a sort of final settlement of past differences.”4

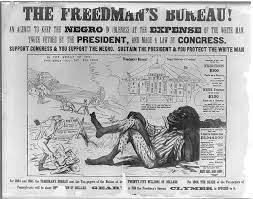

Cartoon showing man with belt buckle “CSA” (Confederate States of America) holding a knife “the lost cause,” a stereotyped Irishman holding club “a vote,” and another man wearing a button “5 Avenue” and holding wallet “capital for votes,” with their feet on an African American soldier sprawled on the ground. Illus. by Thomas Nast in: Harper’s weekly, Sept. 1868 (Library of Congress)

Speaking at Union Square, Douglass recalled that visit and offered it as evidence that “there is in my heart no taint of malice toward the ex-slaveholders.” If formerly enslaved people lacked confidence in “the old master-class,” it was “due to the conduct of that class … since the war and since [their] emancipation.”

And here was the rub. While he did not fault Rutherford B. Hayes as president for “stepping to the verge of his constitutional powers to conciliate and pacify the old master class,” Douglass demanded that “some steps by way of conciliation should come from the other side.” Instead, “freedom of speech and of the ballot have for the present fallen before the shot-guns of the South.” The primary obstacle to reconciliation, in other words, was not wrongs that slaveholders and Confederates had committed in the past but wrongs that ex-slaveholders and ex-Confederates continued to commit in the present.5

Half a world away, Ulysses S. Grant was having similar thoughts. When his presidency ended, Grant happily left its problems behind to embark on a 2-1/2 year long tour circumnavigating the globe. Accompanying him was New York Herald reporter John Russell Young, who interviewed the ex-president on their long voyages and published the results in a book entitled Around the World with General Grant. Like Douglass, Grant readily acknowledged reconciliation’s appeal, though for reasons less grounded in Christianity than in practical politics. Grant spoke from experience when he declared that the desire to “make everybody friendly, to have all the world happy” was an “emotion natural to the office” of the presidency. “There has never been a moment since Lee surrendered that I would not have gone more than half-way to meet the Southern people in a spirit of conciliation,” Grant declared.6

There was only one problem. Ex-Confederates never reciprocated with a willingness to respect African Americans’ rights or to conduct fair elections.

“They have never responded to it,” Grant said. “They have not forgotten the war.” To be sure, a “few shrewd leaders like Mr. Lamar and others have talked conciliation,” Grant acknowledged, referring to U.S. Senator L. Q. C. Lamar. “[B]ut any one who knows Mr. Lamar knows that he meant this for effect, and that at least he was as much in favor of the old regime as Jefferson Davis.”

A former Confederate and the author of Mississippi’s ordinance of secession, Lamar had indeed established a reputation for reconciliationist oratory, including an 1874 eulogy for Charles Sumner delivered in the U.S. House (a speech that helped win him a chapter in John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage). But when Sumner’s Civil Rights Act — whose passage had been his dying wish — later came to the floor, Lamar voted against it (a fact that escaped JFK’s mention). Speaking at the dedication of Charleston’s John C. Calhoun monument in 1887, Lamar defended secession and Calhoun’s views on slavery. A year later, Grover Cleveland named him to the U.S. Supreme Court.7

Americans today — including the new president — can learn a number of things from this history. In his inaugural address, Joe Biden talked much of unity, and also of righting past wrongs. He did not, however, reflect on the relationship between those impulses towards reconciliation and justice, and how they can sometimes be in tension.

Biden, a devout Catholic, might find instructive here the example of Frederick Douglass. A man of faith whose conscience inclined towards forgiveness, Douglass knew from experience in public life how a call for unity could become an excuse to forget. His 1878 Decoration Day speech shows how to combine an appeal for reconciliation with a call to justice.

Grant likewise understood that a “policy of conciliation” that was “all on one side” was doomed to fail. One other lesson, from the 18th president for the 46th: beware “shrewd leaders” on the other side who talk conciliation only “for effect.”8

Footnotes

[1] Frederick Douglass, “There Was a Right Side in the Late War,” in Frederick Douglass Papers: ser. 1, Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, ed. John Blassingame et al., 5 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979–92), 4:480-92; a typescript is also available in the Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress. See also the reports in the New York Times, New York Tribune, New York Herald, May 31, 1878. On Civil War memory, see David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

[2] Douglass, “There Was a Right Side in the Late War,” 485.

[3] Douglass, “There Was a Right Side in the Late War,” 485; Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865; U.S. Grant to Joseph R. Hawley, May 29, 1868, in Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 32 vols., ed. John Y. Simon (Southern Illinois University, 1967-2009), 18:263-64. On the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, see Eric Foner, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (New York: Norton, 2019).

[4] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (Hartford, Connecticut: Park Publishing, 1881), 445-49; David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 593-95.

[5] Douglass, “There Was a Right Side in the Late War,” 486-87.

[6] John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant, 2 vols. (New York: American News Company, 1879–80), 2:359-60. For more on Grant and the memory of Reconstruction, see my piece in the December 2020 issue of the JCWE: “Remembering Reconstruction in Its Twilight: Ulysses S. Grant and James G. Blaine on the Origins of Black Suffrage.”

[7] Young, Around the World, 2: 360.

[8] Joseph R. Biden, Jr., Inaugural Address, January 20, 2021; Young, Around the World, 2: 359-60.