BlackPolitics.org Editorial Position

Callout: Black Electoral Politics is the fault line of American democracy because it was the one force powerful enough to reconfigure Southern society — and the one threat white supremacists most urgently sought to destroy.

Black Electoral Politics Was Structural During Reconstruction — Not Symbolic

During Reconstruction, Black electoral power wasn’t symbolic. It was structural. In South Carolina, Black voters elected a majority of legislators who rewrote the state constitution, abolished racial property requirements, expanded public education, and taxed wealthy landowners to fund infrastructure. In Louisiana and Mississippi, Black voters helped elect significant numbers of legislators who advanced similar reforms — even without holding a full majority — shaping policy through coalition-building and sustained civic pressure. These were not symbolic victories. In South Carolina, Black legislators governed the state — not as tokens, but as architects of a new civic order. In other Southern states, Black lawmakers held substantial seats and shaped policy through alliances, persistence, and strategic leverage. These were blueprints for governance.

White reactionaries understood Black electoral power — and feared it. Their response was not just backlash, but a coordinated campaign of constitutional sabotage. Between 1890 and 1908, every Southern state rewrote its constitution to suppress Black voting rights. These were not isolated reforms. They were strategic reversals designed to erase the gains of Reconstruction and restore white-only rule.

As historian Matthew Davison writes, “Each ballot was seemingly a referendum on a community’s definition of American identity.” Electoral violence wasn’t random — it was concentrated around polling places, registration drives, and legislative chambers.

If Black electoral power wasn’t central, it wouldn’t have required federal troops to protect it — or constitutional amendments to guarantee it. And it wouldn’t have provoked a century of legal warfare to dismantle it.

Electoral politics is the gravitational center because it threatened the racial order at its root — not just socially, but structurally. Every other current of Black politics emerged in response to its betrayal, distortion, or denial.

Sources: History.com: Power Grabs in the South Erased Reforms After Reconstruction

But if electoral politics provoked backlash by threatening the racial order, it also provoked disillusionment — because it has never delivered autonomous power to Black communities.

The Limits of Black Electoral Power: Why Disillusionment Persists

Since Reconstruction, African Americans have rarely exercised majority control in any legislative body capable of independently enacting transformative policy for Black communities. During the 1870s, Black legislators briefly held majorities in Southern states like South Carolina, passing laws that expanded public education and civil rights. But this power was violently dismantled by Redemption governments and never restored.

In the century that followed, landmark victories — from the Civil Rights Act to the Voting Rights Act — were achieved through coalition politics, not Black-majority governance. Even the Congressional Black Caucus, founded in 1971, has never held decisive legislative power. Local exceptions exist: cities like Atlanta, Detroit, and Baltimore have elected Black mayors and council majorities, but state preemption, federal constraints, and economic pressures have often limited their autonomy.

This absence of sustained, autonomous legislative power has fueled deep disillusionment. Many Black leaders, activists, and voters — especially those shaped by grassroots struggle — have never seen electoral politics deliver on its promises. As recent studies confirm, disillusionment now rivals voter suppression as a driver of low turnout among poor and working-class Black Americans.

Yet Electoral Politics remains the gravitational center of Black Politics — not because it has fulfilled its promise, but because it has shaped every other current in response. It was the rise of Black electoral power during Reconstruction that provoked systemic backlash. It was the denial of that power that gave rise to separatist institutions, armed self-defense, and eventually Revolutionary Black Nationalism — a movement rooted in the pursuit of self-governance and independent Black nationhood, the ultimate expression of Black political power.

And it is the ongoing struggle for representation — from local school boards to Congress — that continues to define the terrain of Black political life.

🔥Editorial Spotlight: Rural Black Voters — The Frontline of Black Revolutionary Power

“If you believe in revolution, move South. Not to escape — to govern.”

Across the South, there are over 1,200 towns where Black residents make up at least 30% of the population, and more than 400 towns where they are the majority. These aren’t symbolic battlegrounds — they are strategic strongholds. We’re talking about sheriffs, town councils, school boards, county commissions, and judgeships — the very offices that determine policing, land use, education, and access to justice. In these rural towns, Sheriffs, town councils, school boards, county commissions, and judicial seats are all within electoral reach. These communities are the bedrock of Black civic life, where churches double as organizing hubs, elders carry deep political memory, and local elections are often decided by razor-thin margins. This demographic underscores my central thesis: electoral politics is the fault line and gravitational center of Black political power. This is where you put the hay down so the goats can get it — where strategy meets accessibility, and revolutionary potential becomes actionable governance.

Yet these communities remain ignored, under-engaged by national campaigns, and under-resourced by movement organizers. And let’s be clear: this has nothing to do with the Democratic Party or your views about it. This is about power — the kind of Black political power that was briefly exercised during Reconstruction. Revolutionary power. For Black activists and would-be revolutionaries, these towns are not margins — they are frontlines. Investing in their civic infrastructure, amplifying their leadership, and building coalitions around local issues like land use, healthcare, education, environmental justice, and criminal justice is not just tactical — it is infrastructure work, revolutionary work. These communities don’t need to be discovered — they need to be respected, resourced, and organized.

📊 What We Know About Voter Registration in Black Rural Communities

- Nationally, Black voter registration rates are strong — often higher than Latino and Asian voters, and comparable to white voters in many states.

- In Southern states, Black voters make up a significant share of the electorate:

- In Georgia, for example, African Americans account for one-third of eligible voters.

- However, in rural areas, registration is often suppressed by:

- Limited access to registration sites

- Poor mail infrastructure

- Aggressive voter roll purges

- Lack of outreach from campaigns and civic groups

🧭 What Rural Black Voters Mean for Strategy

Even in towns where Black residents are 30% or 50%+ of the population, voter registration may not reflect that potential. That’s not apathy — it’s architecture. These communities are civically engaged but structurally excluded. Organizers must treat voter registration as infrastructure work, not just outreach.

This reinforces my editorial thesis: electoral politics is the fault line and gravitational center. Registering Black voters in these towns isn’t just tactical — it’s revolutionary. It’s how we rebuild the kind of Black political power last seen during Reconstruction.

Why Local Power Changes Everything

When Black residents in rural towns implement this strategy — registering to vote, building coalitions, and winning local offices — they unlock the ability to directly shape how their tax dollars are spent. Instead of watching resources bypass their communities, they can vote for school board members who prioritize their children, sheriffs who respect their neighborhoods, and county commissioners who invest in roads, clinics, and housing. The connection becomes tangible: your vote decides your budget. This is how civic power turns into clean water, reliable infrastructure, and accountable leadership — not someday, but every fiscal year.

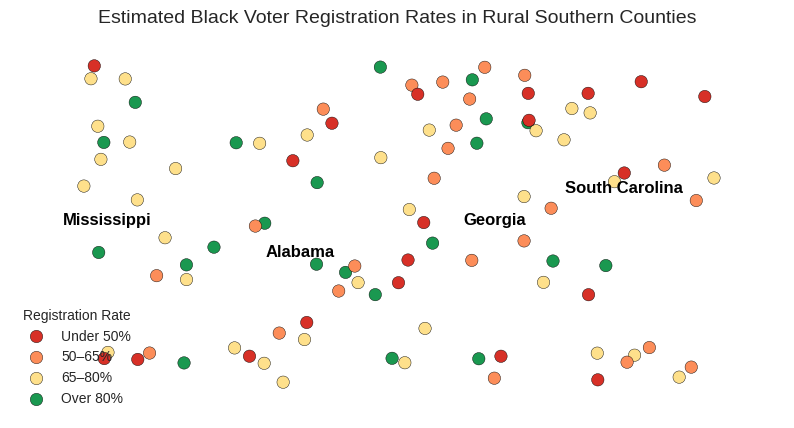

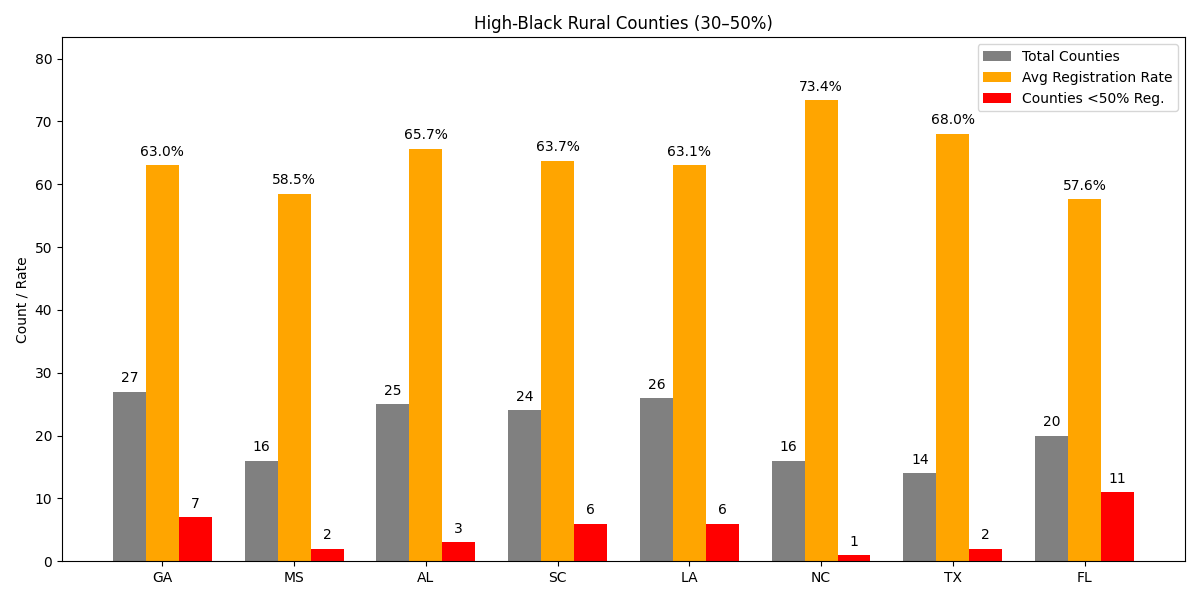

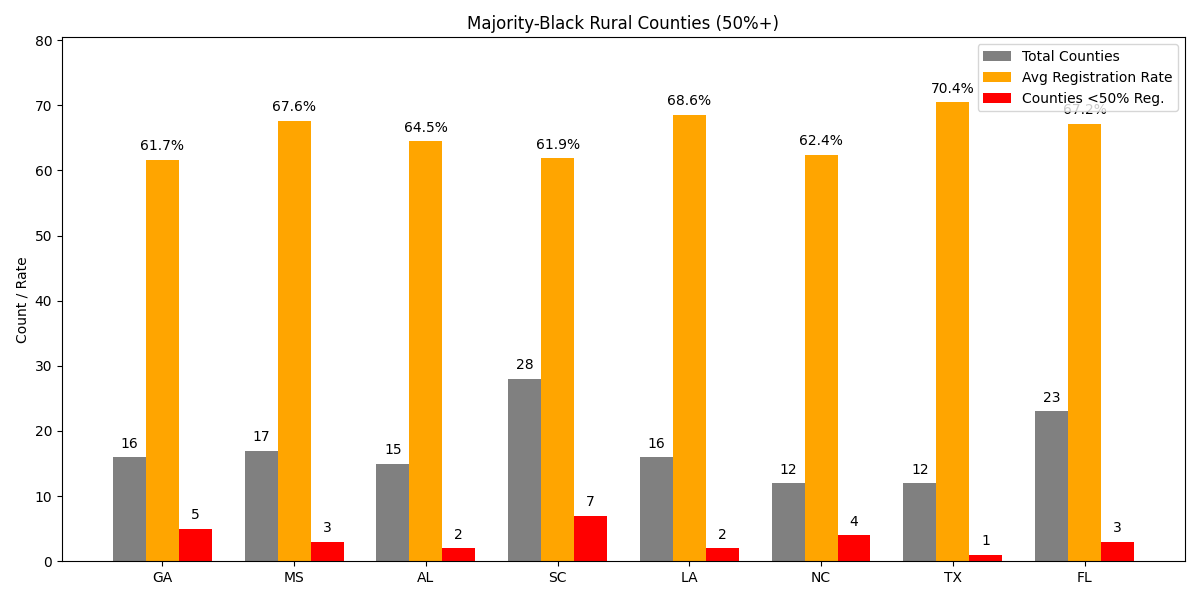

📘 Explainer Block: What These Charts Reveal (as of November 2025)

These charts break down estimated Black voter registration across rural counties in the South, using two key categories:

- Majority-Black counties — where Black residents make up more than 50% of the population

- High-Black counties — where Black residents make up between 30% and 50%

Each chart shows three things for each state:

- How many counties fall into that category

- The average voter registration rate among Black residents

- How many of those counties have registration rates below 50%

🔍 What the Numbers Mean

Let’s take Georgia as an example from the first chart:

- There are 27 rural counties in Georgia where the Black population is between 30% and 50%.

- The average Black voter registration rate across those counties is 63%.

- Of those 27 counties, 7 have registration rates below 50% — meaning nearly a quarter of these high-Black counties are still facing significant barriers to civic participation.

This pattern repeats across the South. In majority Black counties, Black voters already have the numbers to win local offices — sheriffs, school boards, judgeships, and more. But in many of these counties, registration rates are still below 50%. That means power is within reach, but not yet activated.

In high-Black counties, Black voters may not be the majority, but they’re a large enough bloc to shape outcomes — especially when joined by allies. These counties often have slightly higher registration rates, but still face serious barriers.

The “Counties Below 50% Registration” bars highlight suppression zones — places where voter registration is artificially depressed through infrastructure decay: poor mail access, limited registration sites, and aggressive purging of voter rolls.

🧱 Why This Matters

This isn’t just about numbers — it’s about strategy. These counties are where Black civic power can be built, exercised, and defended. They’re not symbolic battlegrounds. They’re the frontlines of governance.

If you’re an organizer, researcher, or funder, these charts help you answer three questions:

- Where is Black power already demographically possible?

- Where is it being suppressed?

- Where should we invest next?

Black Electoral Politics is not the endpoint. It is the fault line.

⚖️ A Double Challenge: Power Without Illusion

If electoral politics provoked backlash by threatening the racial order, it also provoked disillusionment — because it has never delivered autonomous power to Black communities. Since Reconstruction, African Americans have rarely held majority control in any legislative body capable of enacting transformative policy. The party system itself — arcane, hierarchical, and often hostile to grassroots leadership — has pushed many organizers to the margins, where their time and energy are spent resisting harm rather than shaping policy.

But this editorial issues a challenge:

What if the most committed grassroots organizers, cultural workers, and movement leaders concentrated their power on strategic local races — not as a compromise, but as a confrontation?

📚

History offers proof that this is not naïve. It is insurgent:

- Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964): Born from SNCC and local sharecroppers, this party challenged the legitimacy of the all-white Democratic delegation and redefined what representation could mean — even without formal power.

- Harold Washington’s coalition in Chicago (1983): A multiracial, working-class alliance broke through entrenched machine politics to elect the city’s first Black mayor, reshaping patronage, budgeting, and accountability.

- Working Families Party (1998–present): Though not Black-led, it has shown how fusion voting and local insurgency can pressure Democrats from the left and win material gains — including eviction protections, paid sick leave, and progressive prosecutors.

- School board takeovers in Prince George’s County, MD and Jackson, MS: Black-led coalitions have used local elections to shift curriculum, funding, and discipline policy — often with more impact than national races.

- After Freddie Gray’s death in Baltimore: Marilyn Mosby’s election and prosecution of six officers marked a rare moment of grassroots power confronting the racial order. Her tenure revealed both the potential of strategic local races and the fragility of that power when not backed by broader legislative or institutional control.

- In 2025, Zohran Mamdani’s grassroots campaign: Unseated a political dynasty in New York City. His election as the city’s first Muslim and South Asian mayor marked a generational shift — but also raised urgent questions about how movement-backed candidates govern within hostile systems.

History offers proof that this is not naïve. It is insurgent:

- Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964): Born from SNCC and local sharecroppers, this party challenged the legitimacy of the all-white Democratic delegation and redefined what representation could mean — even without formal power.

- Harold Washington’s coalition in Chicago (1983): A multiracial, working-class alliance broke through entrenched machine politics to elect the city’s first Black mayor, reshaping patronage, budgeting, and accountability.

- Working Families Party (1998–present): Though not Black-led, it has shown how fusion voting and local insurgency can pressure Democrats from the left and win material gains — including eviction protections, paid sick leave, and progressive prosecutors.

- School board takeovers in Prince George’s County, MD and Jackson, MS: Black-led coalitions have used local elections to shift curriculum, funding, and discipline policy — often with more impact than national races.

- After Freddie Gray’s death in Baltimore: Marilyn Mosby’s election and prosecution of six officers marked a rare moment of grassroots power confronting the racial order. Her tenure revealed both the potential of strategic local races and the fragility of that power when not backed by broader legislative or institutional control.

- In 2025, Zohran Mamdani’s grassroots campaign: Unseated a political dynasty in New York City. His election as the city’s first Muslim and South Asian mayor marked a generational shift — but also raised urgent questions about how movement-backed candidates govern within hostile systems.

These examples are not perfect. They are not permanent. But they prove that electoral politics can be weaponized — not worshipped.

🔥 Call to Action

If we know the system is rigged, then we must rig it back.

Not by waiting for party elders to bless us, but by building independent infrastructure, running unapologetic candidates, and treating every local race as a site of insurgency.

Electoral Politics is not the endpoint. It is the fault line.

And fault lines are where earthquakes begin.

— Selwyn, Editor-in-Chief

11/3/2025

Editor-in-Chief

administrator

The Editor-in-Chief of BlackPolitics.org leads the platform’s strategic vision, editorial integrity, and archival design. With deep experience in national, state, and local campaigns — including efforts to build and strengthen independent Black political parties — the Editor-in-Chief bridges historical insight with technical innovation. Grounded in African American history, voting rights advocacy, and coalition strategy, the Editor-in-Chief has helped shape sustainable tools for Black political empowerment. From digitizing legacy archives to developing scorecards, timelines, and policy trackers, the Editor-in-Chief ensures that every post reflects a commitment to truth, transparency, and collective power.

The Editor-in-Chief’s contributions span decades of movement history — from New York City community activism and voter mobilization, to the Southern organizing tradition, and onward to modern digital mobilization — always rooted in rigorous documentation and future-ready infrastructure. Through collaborative design, the Editor-in-Chief has helped build archival systems that connect historical records to actionable advocacy.

✍️ BlackPolitics.org | Editor-in-Chief

Empowering communities through data, history, and collaborative action