Smithsonian Museums Are Supposed to Tell the American Story. So Where’s the Latino Museum?

When I was growing up in San Antonio, Mexican culture permeated every aspect of American culture. I heard Spanish every day: at the grocery store, on the playground and, of course, at home. The staples in the school cafeteria included corn dogs, but also cheese enchiladas. Kids of every background broke piñatas at their birthday parties. But in large parts of America, Latinos were seen as foreigners and outsiders, mentioned only in the context of drugs, gangs or immigration news. Not much has changed.

In September 2019, President Trump asked during a rally in New Mexico, “Who do you like more- the country or the Hispanics?” The framing of this question ignores the fact that in the United States, Americans and Latinos are one and the same. There are 58.9 million Latinos in America, about 63% of whom are of Mexican descent. While some of us are immigrants, as of 2015, 65.6% of American Latinos were born in the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center. And many more Latinos have roots in this land that date back centuries.

One reason Latinos and Americans are cast as two distinct groups is America’s obsession with assimilation to white culture. Only as a white person in America is your Americanness not in question. Some people, like our President, have no problem denigrating the rest of us simply because of the color of our skin. But another reason Latinos are viewed as outsiders is our erasure from the American consciousness. When the role of Latinos in American history is overlooked and Latinos hold a disproportionately small number of prominent positions, many people just aren’t aware of our deep roots in America or our economic, cultural and military contributions. The harm of not being treated as valuable members of this country can be seen in the rise of anti-Latino hate crimes, as well as in the higher rate of depression among Latino youth than their white peers.

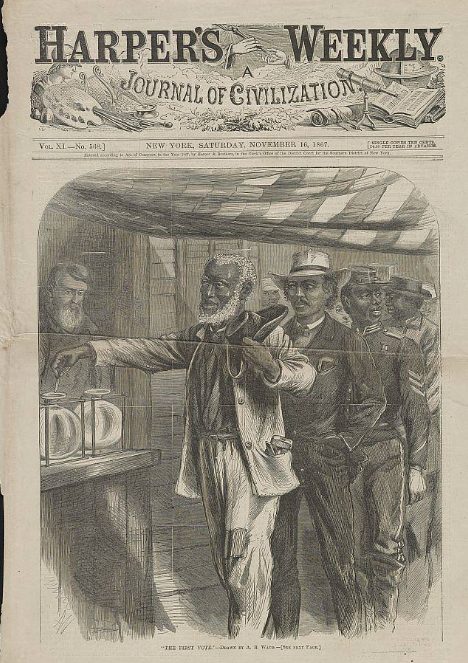

That’s why since 2004, the nonprofit organization Friends of the American Latino Museum has been advocating for the creation of a Smithsonian museum in our nation’s capital “to educate, inspire, and encourage respect and understanding of the richness and diversity of the American Latino experience within the U.S.” A Smithsonian museum dedicated to Latino history and culture may seem like frivolous desire for a trophy. But the national Smithsonian institutions are tasked with officially recounting the American story, and slowly they have included significant parts of our nation’s history – the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall opened in September 2004, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in September 2016. But how can they fulfill their mission when such a large part of American history is still missing?

The Smithsonian Latino Center has taken an important first step by developing the Molina Family Latino Gallery (opening in 2021) in the National Museum of American History, which will be the “first dedicated museum space on the National Mall celebrating the U.S. Latino experience.” But a 4,500-square-feet exhibition in an existing museum is not enough to tell our story, especially when you consider that the National Air and Space Museum is some 161,000 square feet. We need and deserve a museum of our own.

On October 17, a number of prominent Latino activists and public figures will testify for the first time before the House Natural Resources Committee on the need for this institution, reminding them that Latino history is American history. A museum devoted to American Latinos could educate visitors about the stories our history textbooks largely ignore. Many people don’t know, for instance, about the Latinos who died defending the Alamo, the Tejanos who helped lead Texas to independence and later found themselves second-class citizens in their own land. They aren’t aware that Spanish was spoken in what is now the United States before the Mayflower arrived. They have never heard about the 400,000 to 500,000 Latino soldiers who fought in World War II or the more than 800,000 Latinos who served with distinction in Vietnam.

The role of Latinos in the fight for civil rights is also mostly missing from history lessons. One of the largest student walkouts in U.S. history happened in East Los Angeles in 1968 as 22,000 high school students protested for better education conditions for Latinos. In 1969, students in Crystal City, Texas, organized walkouts to defeat a policy at their high school that capped the number of Mexican-American cheerleaders at one, fueling a larger fight that led to not only the elimination of quotas for the cheerleaders, but the addition of bilingual education, Chicano studies, Mexican food in the cafeteria and more. Within two years the school board and city council better reflected the city’s population. Eight years before Brown vs. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case that legally desegregated schools in America, a Latino family fought and won a school desegregation case in California called Mendez v. Westminster. The NAACP filed the amicus brief in the Mendez case, and Richard Kluger, the author of Simple Justice: The History of Board vs. Brown of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality, called it “a useful dry run” for Brown vs. Board.

This erasure doesn’t just apply to the past. Today our faces and voices are mostly absent across industries. Look at the entertainment world for just one example: The 2019 UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report found that, while Latinos are 18% of the U.S. population, they accounted for only 6.2% of roles in broadcast scripted shows and only 5.2% in movies, compared to 63.3% and 77% held by white actors, respectively. Wanting our stories to be told, our history to be taught and our faces to be seen isn’t a vanity project. Representation matters because as long as we remain invisible, we will remain targets for hateful rhetoric, policies and actions against our community.

On August 3, 2019, a white nationalist killed 22 people in a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, as “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas,” as he professed in a manifesto prior to the shooting. But maybe, just maybe if he had learned the full history of Texas – which includes both the Mexican heroes of the Texas independence and the Latinos heroes of every American war — or if he had been taught that Mexicans have been part of Texas long before the Mexican government invited Anglo-settlers to help populate the land, he would not have viewed us as targets, but as fellow countrymen. It’s possible that if he had learned these things, our brown skin would not have caused such rage and anger. Perhaps, if he had watched our stories on his television, the rare ones that don’t portray us as drug dealers and criminals, he would have grown up to view Latinos as the Americans that we are.

As long as we remain in the shadows, people will continue to view us as the “other” or as newcomers, but it’s not that we are newly arrived in America — it’s that America hasn’t recognized our existence.

The Smithsonian American Latino Museum Act has 212 bipartisan co-sponsors in the House and the 25 in the Senate. But the legislation has not made it out of committee. Major presidential candidates including Senators Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris and Corey Booker have signed on to the bill. Senator Bernie Sanders has not. The Latino community cannot wait to be seen, and America can no longer deny us the opportunity to tell our story. I cannot think of a more critical time for a museum on the National Mall to celebrate our history and contributions and to help erase the divide between Latino and American. Our time is now.

VIA Time