How the Community Service Society and the 1991 Redistricting Quietly Rewired New York City Politics

I. Introduction: The moment no one saw coming

Remapping NYC 1991 ignited the moment when communities of color seized a once‑in‑a‑generation chance to rewrite who held power in New York City.

Between 1989 and 1991, New York City’s political architecture cracked wide open. A Supreme Court ruling blew up the old Board of Estimate. The NYC Charter Revision Commission adoped a new city charter that expanded the City Council from 35 to 51 seats. And suddenly — for the first time in the city’s modern history — Black, Latino, and Asian communities had a real shot at reshaping who governed them. For the first time, the city’s shifting legal and political landscape opened a path toward genuine NYC minority representation.

Most people remember the headlines. Very few remember the infrastructure behind the scenes.

This is the story of how the Community Service Society of New York (CSS), under the leadership of David R. Jones, seized that opening — and how the work I began in Countdown ’88 and ’89 that helped lay the groundwork for the city’s first African American mayor converged with the rising ambitions of Brooklyn’s organizers, Caribbean civic leaders, immigrant advocates, and community activists across the city who suddenly saw that redistricting could be a pathway to real power — and how, together, we reshaped the balance of power in New York City.

It wasn’t inevitable. It was built.

II. Before the maps: the convergence no one has written about

Countdown 88 set the stage for the CSS Districting Project

Beginning in 1987, under the leadership of David R. Jones, the Community Service Society made a deliberate shift beyond direct services and research into nonpartisan political participation work, grounded in a simple premise: the poor could not defend themselves without political power.

CSS analysts had uncovered a structural crisis: more than two million New Yorkers were unregistered, disproportionately African American, Latino, Asian, and poor. In response, CSS launched an unprecedented voter‑engagement initiative and went to federal court to block a massive voter purge that disproportionately targeted minority communities.

This is the context in which the CSS Districting Project emerged. It was not an afterthought or a reaction. It was the next step in a strategy CSS had already adopted in the late 1980s.

Countdown 88 and Countdown 89 were citywide voter‑registration and mobilization campaigns that brought together community organizations, churches, unions, and civic leaders to confront the scale of political exclusion in New York City. These efforts helped register hundreds of thousands of new voters and created the civic momentum that contributed to the election of the city’s first Black mayor in 1989.

For CSS, these campaigns were not external events but confirmation that large‑scale mobilization was possible — and that the next step had to be structural.

Mobilization → Organizing → Representation. Countdown 88 and 89 built the civic muscle. The CSS Districting Project built the representational architecture.

The convergence mattered.

III. The rupture: the New York City Board of Estimate falls — and the city’s power structure is suddenly in play

When the Supreme Court struck down the Board of Estimate in NYC Board of Estimate v. Morris (1989), most of New York shrugged. The newspapers covered it like a technicality. City Hall treated it like a bureaucratic inconvenience. But inside CSS, the ruling landed differently.

David R. Jones — president and CEO of CSS — understood immediately what it meant. The ruling didn’t just eliminate an outdated and unconstitutional governing body. It blew a hole in the city’s political architecture.

It forced New York City to:

- abolish the Board of Estimate

- expand the City Council from 35 to 51 seats

- redraw every district in the city

- submit the new map to the U.S. Department of Justice

This was the kind of structural opening that appears maybe once in a generation. And David had the clarity — and the courage — to say:

CSS is stepping into this fight.

That decision changed the trajectory of New York City politics.

The Charter criteria that shaped the battlefield

The 1989 Charter required the Districting Commission to follow three core principles:

- One person, one vote — no district could deviate more than 10% from the ideal population.

- Fair and effective representation — districts had to protect the voting rights of racial and language minorities.

- Neighborhood integrity — communities with shared interests had to be kept intact.

These criteria became the legal backbone of CSS’s strategy.

The Justice Department’s role

Because Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx were covered under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the final map required federal preclearance. Any plan that diluted minority voting strength could be rejected.

This gave CSS a powerful lever: If the Commission failed to meet the standard, the Justice Department could stop the map.

IV. The pivot: CSS decides to build power, not just register voters

On February 2, 1990, in response to David R. Jones’s request for a strategic assessment, I sent him a memo outlining a new direction for CSS’s political development work. The memo was blunt: New York was entering a once‑in‑a‑lifetime opportunity, and if CSS did not intervene, the communities mobilized through Countdown ’88 and Countdown ’89 would see their gains evaporate in the redistricting process.

I wrote plainly that “while the election of David Dinkins as mayor of New York was a necessary and inspiring victory for the disenfranchised, it is not community empowerment.” I went further, arguing that “the Society will have the ability to take advantage of a ‘once in a lifetime opportunity’ created by the new city charter’s call for the creation of an expanded City Council… Given the impact that council persons will have on the city budget and delivery of services, an important community empowerment initiative would be to ensure that the optimum number of districts for minorities are cut and that minority candidates who represent the best interests of those communities are elected in those districts.”

The memo made the case that CSS had to move beyond mobilizing voters and begin shaping the structures that determined whether those voters would ever hold real power.

The argument rested on two insights shaped by my recent visit to the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project in Texas:

- Redistricting was not a technical exercise but a political battlefield.

- Organizations that combined data, legal strategy, community organizing, and public education could fundamentally reshape political power — if they acted early.

The memo laid out a seven‑part program for CSS:

- Analyze the city’s demographic and electoral landscape

- Develop a full alternative 51‑district map

- Educate communities

- Mobilize neighborhood‑based coalitions

- Engage the media

- Prepare legal strategies

- Build long‑term organizational capacity

The core claim was simple and urgent:

If we don’t intervene, the communities we just mobilized will lose the power they fought for.

David didn’t hesitate. He backed the project — fully, publicly, and institutionally.

V. Building the machinery: turning the memo into an operational strategy

Once David endorsed the plan, the February 2 memo became the blueprint for the Districting Project’s day‑to‑day work. Six of the seven areas of work were developed into full operational tracks with staff, partners, and timelines. The seventh — building long‑term organizational capacity — never materialized, a gap I later identified as a core structural failure.

The dress rehearsal

Months before the census data arrived, CSS conducted a full dress rehearsal using 1980 census data, immigration patterns, and birth statistics to model where minority population growth had occurred. This ensured that when the real data arrived, CSS would be ready.

The civil‑rights alignment

Before drawing a single line, CSS convened the major civil‑rights and voting‑rights organizations — NAACP LDF, PRLDEF, AALDEF, NYCLU, and others — to align standards and avoid fragmentation.

The seven tracks (summarized)

- Mapping the landscape

- Producing a full alternative map

- Educating communities

- Mobilizing coalitions

- Engaging the media

- Preparing legal strategies

- Building long‑term capacity

Together, these tracks transformed the Districting Project from an idea into an institution.

Of the seven tracks I outlined in my memo to David R. Jones, the only one we failed to fully realize was the long‑term organizational capacity piece. As I noted in my original report, the deeper failure was structural:

“The Society had a unique opportunity to utilize the Districting Project to train expertise in the minority communities. In retrospect, while the decision to restrict the involvement of community based organizations in the formation of the CSS alternative plan facilitated the efficient and expeditious development of that plan, it ensured that the methodology utilized would not be passed on to others. Likewise, the internal organizational structure which separated the technical and political components of the CSS project from each other, restricted the learning of the high technology redistricting skills to the traditional social researchers within CSS and was contrary to the political empowerment goals of the agency which sought to empower the minority poor so they can help themselves. Because the political team from the project was the one which maintained regular interaction with the representatives of the minority poor communities, their separation from the high technology redistricting functions meant that the opportunity to transfer those skills to the minority communities had been lost.”

VI. Inside the machine: data, maps, organizers, and law

With six of the seven tracks in place, CSS built the physical and analytical infrastructure needed to execute them. What emerged looked less like a traditional nonprofit program and more like a political command center.

The team

CSS also brought in outside consultants with national redistricting experience, including experts in Voting Rights Act litigation, demographic modeling, and racial bloc voting analysis. Their role was to pressure‑test our assumptions, validate our projections, and ensure that our alternative map met both the legal standards and the representational goals we were advancing. These consultants included:

- John Flateau – political/geographic consultant and campaign technician

- Randolph Scott McLaughlin — law professor and Voting Rights Act litigator

- Darryl Montgomery — statistician and demographic modeler

- Dr. James Loewen — national redistricting expert and specialist in racial bloc voting

The situation room

CSS built a situation room with wall‑sized maps, plotters, and the most advanced redistricting software available at the time. Every wall carried layers of information — census tracts, precinct lines, racial bloc‑voting patterns, immigration corridors, community board boundaries, and election returns involving Black, Latino, and Asian candidates.

Why CSS ignored existing political boundaries

CSS deliberately avoided starting from existing Council or Assembly districts, which would have advantaged incumbents. Instead, the team began with:

- thematic maps (displaying racial demographic data by map color)

- community planning board boundaries

- demographic clusters

This ensured the map reflected communities, not politicians.

The central question

How many districts could be drawn where communities of color could elect candidates of their choice?

The early projection — before the census data arrived — was 21 districts.

Then the 1990 census data arrived.

VII. The numbers shift — and the city shifts with them

When the 1990 census data finally arrived, it confirmed what our organizing, fieldwork, and modeling had already suggested: New York City had become a majority Black, Latino, and Asian metropolis.

Our revised analysis showed that the city could support 27 minority‑opportunity districts, not 21.

Brooklyn

- Up to 8 Black/Caribbean districts

- A new Latino‑influence district

- An emerging Asian‑influence district in Sunset Park

The Bronx

- 3 Black districts

- 3 Latino districts

Queens

- 2 Black districts

- 1 Latino district

- 1 Asian‑influence district — the first of its kind

Manhattan

- 2 Black districts

- 1 Latino district

Staten Island

- A stable district where Black and Latino voters could influence outcomes

These weren’t abstract numbers. These were new political futures.

CSS stood alone. We were the only organization in New York City — other than the Districting Commission — with the technical capacity to produce a full 51‑district plan.

Then came the sequence that reshaped the entire redistricting fight.

SIDEBAR: “Opening Shots Fired in Redistricting War” — New York Post, April 19, 1991

The first public shockwave came in April, when the New York Post reported that the CSS map had upended the political landscape:

- Bronx Congressman José Serrano and Borough President Fernando Ferrer warned the Commission that if it failed to draw fair districts, they would take the fight to the Justice Department.

- Their argument rested squarely on CSS’s analysis: 27 minority‑opportunity districts, including 13 Black and 10 Latino districts.

- The Post noted that the CSS map “put pressure on the Commission” and had become the standard against which the official plan would be judged.

- A commissioner privately asked Ferrer why Latino leaders weren’t “lobbying” them — a remark Ferrer publicly rejected, insisting that census data, not political access, must drive the process.

The Post captured the early tremors — but the political earthquake came six weeks later.

On Tuesday, June 4, 1991, The New York Times published the Districting Commission’s adopted map on page 1 of the Metropolitan section. Although the Times did not print the CSS map itself, its analysis reflected the very issues our plan had forced into the center of the debate — the number of minority‑opportunity districts, the distribution of Black and Latino political power, and the stakes of the new 51‑district council.

The Times’ reach, credibility, and front‑page placement transformed the moment. By treating the representational questions raised by CSS as the defining lens for understanding the Commission’s map, the Times effectively validated our work. From that point forward, every proposal, every hearing, and every negotiation was measured against the standards CSS had already set.

VIII. The political field reacts — and CSS becomes the reference point

Even before CSS published its alternative map, the staff were aggressively preparing under‑represented communities across New York City for the fight ahead. CSS organized more than a dozen community forums, using overhead projectors and thematic maps to explain the new City Charter, the expanded powers of the City Council, and the demographic patterns — Black, Latino, and Asian — that could form the basis of new districts. CSS’s long‑standing reputation as a nonpartisan civic institution gave these forums unusual credibility, allowing communities to trust the information and engage the process on their own terms. This public‑education campaign also included formal testimony by CSS staff at Commission hearings, all aimed at equipping communities to demand fair and effective representation NYC. That groundwork built the civic literacy and political expectation necessary for the publication and dissemination of the complete CSS 51‑district alternative plan.

Once the CSS map entered the public arena, the conversation shifted immediately. What had begun as community education became a citywide political reckoning.

Latino leaders in the Bronx invoked CSS’s numbers as leverage. Civil‑rights groups cited CSS’s analysis in testimony. Community organizations used the Community Service Society map as a tool for mobilization.

From this point forward, every public hearing, every press conference, every editorial, and every negotiation unfolded in the shadow of the CSS map.

IX. The magnet: CSS becomes the crossroads of a new political generation

Once CSS turned redistricting into a community organizing strategy, the entire city started showing up.

Not just activists. Not just neighborhood leaders. But every ambitious organizer, every emerging strategist, every would‑be candidate who understood that the future of New York politics was being drawn — block by block — in those rooms.

The rooms were electric.

Picture it:

- folding chairs jammed into church basements

- wall‑to‑wall maps covered in tape and marker

- organizers arguing over census blocks like chess pieces

- labor leaders next to tenant organizers

- Caribbean civic associations next to Korean small‑business groups

- ministers, PTA presidents, block captains, and future candidates all in one room

People weren’t coming to “learn about redistricting.” They were coming because they could feel that power was being redistributed — and they wanted to be in the room where it was happening. They wanted a piece of it.

This is where the Clarke story begins

The first time I met Una Clarke — the matriarch of one of Brooklyn’s most influential political families — was at a CSS community empowerment meeting on redistricting.

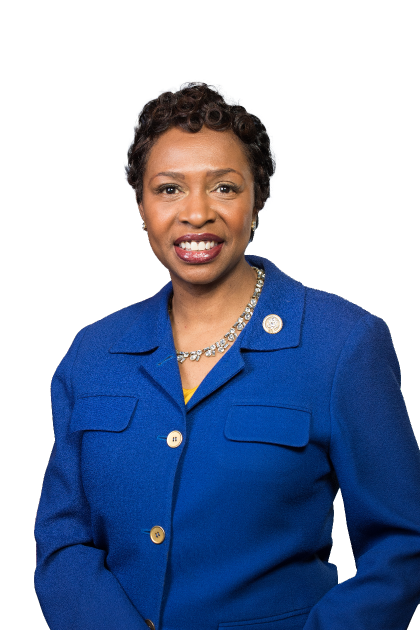

The district Una Clarke eventually won — and the political base her victory helped establish — later became the platform from which her daughter, Yvette Clarke, succeeded her on the City Council and ultimately launched her successful run for Congress.

And today, Yvette Clarke is Chair of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Trace that lineage backwards and you land right back in those CSS rooms — the rooms where:

- communities learned how district lines worked

- leaders emerged

- coalitions formed

- political futures were seeded

And it wasn’t just the Clarkes.

Through this process, I met:

- Nick Perry, later U.S. Ambassador to Jamaica

- Adam Clayton Powell IV, continuing the Powell legacy

- dozens of organizers who later ran for City Council, Assembly, and Congress

When the dust settled — when the maps were finalized, the primaries held, and the new Council elected — the impact of that gravitational pull became unmistakable.

X. The result: a new political landscape

SIDEBAR: The New York Times Weighs In

The New York Times framed the 1991 elections as a turning point:

- praise from civil‑rights advocates

- anger from incumbents

- recognition that the city’s political map had been fundamentally altered

The Times validated what communities already knew: the representational architecture had changed.

The 1991 City Council elections produced the most diverse legislative body in New York City history.

New districts elected:

- Black councilmembers in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx

- Latino councilmembers across multiple boroughs

- the city’s first Asian‑influence district

The representational architecture we helped build became the foundation for:

- the Clarke political lineage

- the rise of new Black and Latino leadership

- the diversification of city government

- the empowerment of neighborhoods long shut out of power

XI. Closing: the history behind the history

In the end, the story of the 1991 redistricting is not just the story of a Supreme Court ruling or a new city charter. It is the story of how a social service institution — led by David R. Jones and powered by my vision, our team’s technical brilliance, and the hunger of communities across the city — stepped into a once‑in‑a‑generation opening and refused to let history repeat itself.

It is the story of how Countdown ’88’s mobilization aligned with the community empowerment aspirations rising across the city — and with CSS’s own empowerment philosophy — to create a new political architecture for New York City.

It is the story of how maps became movements, how community meetings became launching pads, and how a young generation of leaders — from Una Clarke to Yvette Clarke to Nick Perry and beyond — found their political footing in rooms filled with folding chairs, wall‑to‑wall maps, and the belief that representation was not a gift but a right.

XII. Epilogue: the architecture endures

More than three decades later, the legacy of the 1991 redistricting is still visible in the political landscape of New York City. The districts drawn in that cycle — and the representational logic behind them — became the foundation for a generation of Black, Latino, and Asian leadership.

They shaped the rise of the Clarke family, the ascent of Nick Perry, the diversification of the Council, and the normalization of minority opportunity districts as a civic expectation rather than an exception.

The principles CSS advanced — fair and effective representation, neighborhood integrity, and the right of communities to elect candidates of their choice — have since become embedded in the city’s political DNA.

They continue to guide debates over voting rights, charter reform, and the meaning of representation in a multiracial metropolis.

The story of Remapping NYC 1991 is not simply a historical episode. It is a blueprint for how institutions, data, law, and community power can converge to reshape a city — and a reminder that representational justice is never given. It is built.