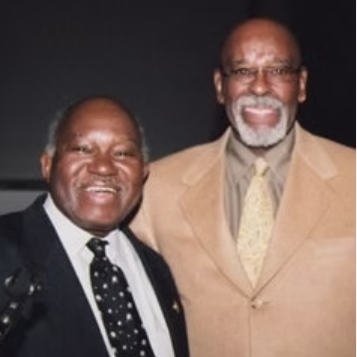

John Flateau Brooklyn Political Strategist and builder of Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure - photo courtesy of the Flateau family - wife Lorraine-Witherspoon-Flateau and son, Marcus Flateau

John Flateau: Brooklyn’s Master Political Strategist

Introduction: The Invisible Architect of Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure

John Flateau Brooklyn political strategist and campaign manager was a master tactical genius who built the Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure that helped elect a generation of Black elected officials and transform New York City politics from the 1970s through the 1990s. A brilliant tactician with deep roots in Brooklyn’s Black community, Flateau worked on campaigns across the borough and beyond, advising Jesse Jackson’s 1988 New York operations, serving as David Dinkins’s chief of staff, and mentoring future leaders including Congressman Hakeem Jeffries and New York State Attorney General Letitia James.

Editor’s Note: My relationship with John Flateau goes back decades. We first met in the late 1970s during the formation of the Brooklyn-based Black United Front, which emerged in response to the police killing of Black businessman Arthur Miller Jr. BUF was headquartered at Rev. Herbert Daughtry’s House of the Lord Church, and all serious activists involved in Black community struggle passed through there. I served, along with several others, on BUF’s Central Committee.

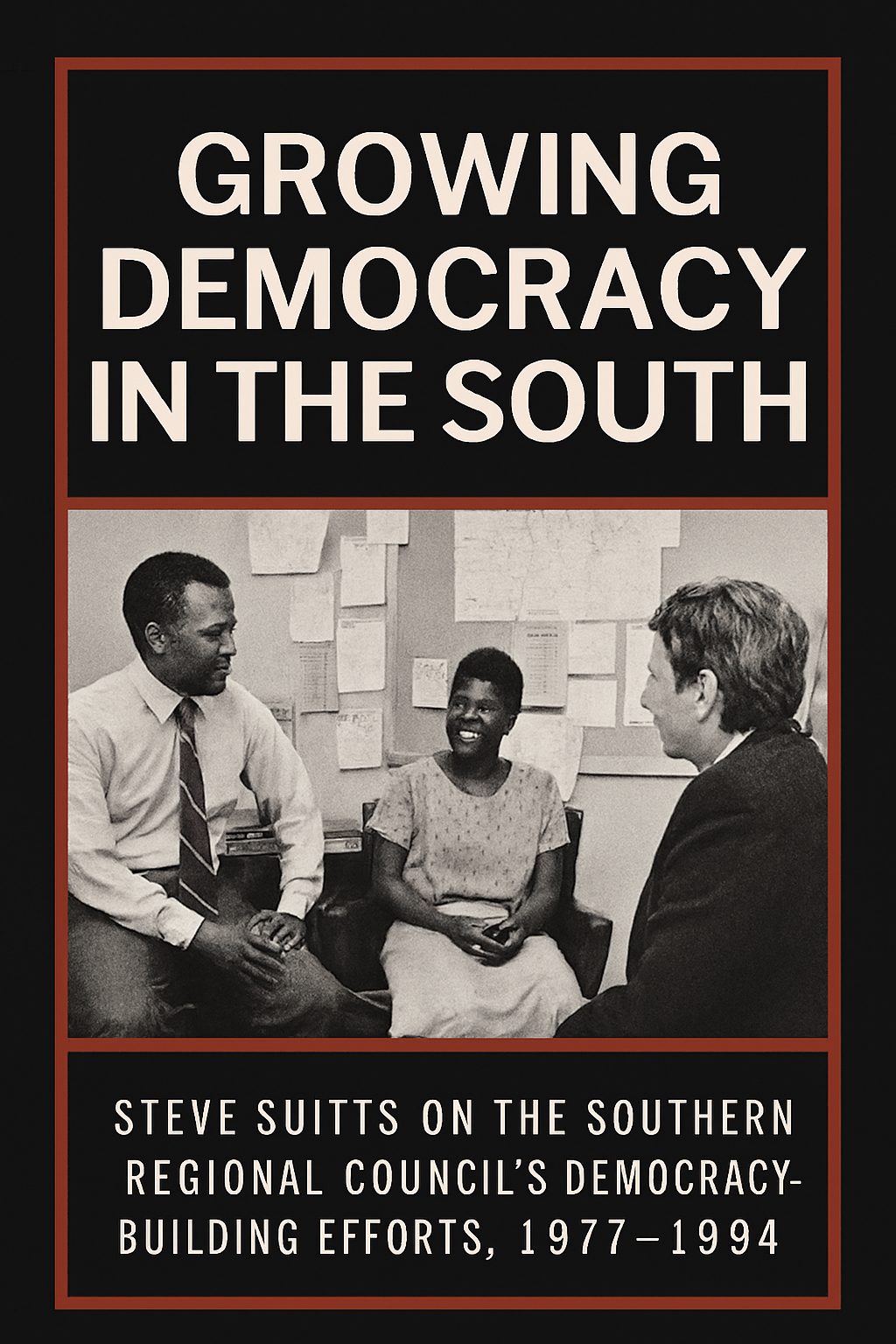

Over the years, Flateau and I became close friends and stayed in regular contact until his untimely death. We exchanged notes, talked on the phone, and collaborated on political strategy up until October 23rd, 2023, two months before he died. John Flateau was my comrade, mentor, teacher (literally), colleague, trainee, consultant, and more. When I attended the New York-based Graduate School of Political Management, John Flateau was my campaign management professor. When I directed voting rights programs at the Atlanta-based Southern Regional Council, John Flateau was a grant recipient in a program I administered that trained voting rights professionals and advocates in the skills necessary to serve as expert witnesses in voting rights litigation. When I directed Countdown 88/89 and the subsequent CSS NYC Redistricting Project, John Flateau served as our redistricting campaign political and geographic consultant. His wife, Lorraine Witherspoon-Flateau, served as the Brooklyn coordinator for Countdown 88.

When Rep. Hakeem Jeffries became House Democratic Leader in 2023—the highest position ever held by a Black elected official in Congress—few outside Brooklyn’s political circles knew the name of the man who had built the Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure that made Jeffries’s rise possible. When Rep. Yvette Clarke became Chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, or when Letitia James became the first Black woman Attorney General of New York, the media focused on their historic achievements without recognizing the decades of patient organizing of Black political power Brooklyn that preceded them.

That invisible architect was Dr. John Louis Flateau—professor, political strategist, redistricting technical expert, voting rights champion, and for more than four decades, the chief technician of Brooklyn’s Black electoral machine. Flateau didn’t seek the spotlight. He built the machinery that put others there.

Flateau passed away suddenly on December 30, 2023, at age 73, leaving behind a legacy that transformed Brooklyn from a “colonized” political landscape controlled by white party bosses into the epicenter of Black political power in New York—and arguably the nation. His death prompted an outpouring from elected officials whose careers he had shaped. Jeffries called him “a brilliant strategist, electoral tactician, scholar and community leader” who “helped to usher in an era of Black political empowerment in Central Brooklyn in the 1980s and 1990s that positively transformed the community and lives on to this day.”

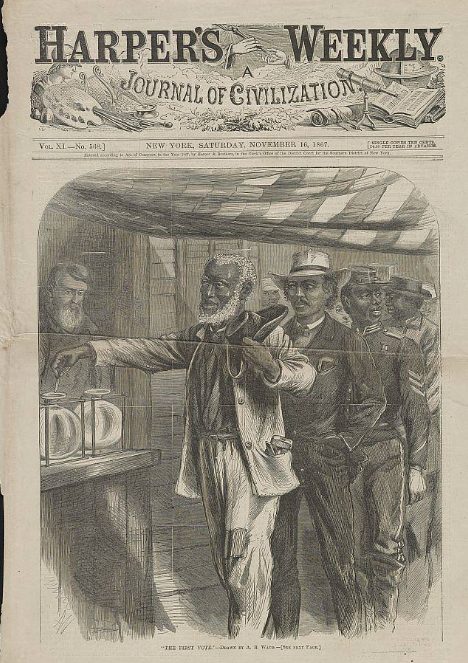

But Flateau’s significance extends beyond the leaders he helped elect. John Flateau Brooklyn political strategist embodied a particular approach to Black political power—one rooted not in revolutionary ideology, theory, or rhetoric but in the patient, systematic work of electoral organizing: voter registration, coalition-building, redistricting, field operations, and the unglamorous mechanics of democratic participation. In an era when many activists dismiss electoral politics as insufficient or compromised, Flateau’s life is a master class, demonstraing how democratic infrastructure, built deliberately over decades, can fundamentally reshape power relationships. Flateau, whose family roots are from Louisiana, embodied a legacy of Black electoral politics stretching back to Reconstruction. During that brief, revolutionary period following the Civil War, formerly enslaved Black people built political infrastructure from scratch—registering voters, forming coalitions, winning elections, and exercising power that terrified white supremacists into a century of violent backlash. Flateau’s work in Brooklyn echoed that Reconstruction legacy: the painstaking construction of electoral machinery that could translate demographic presence into political power, the understanding that true revolution often looks like voter registration drives and redistricting fights rather than dramatic confrontation.

Malcolm X, often misunderstood as dismissive of electoral politics, articulated this understanding powerfully in his 1964 ‘Ballot or the Bullet’ speech. While demanding that Black communities be prepared to defend themselves if democratic participation failed, Malcolm actually emphasized the strategic power of voting. He explained how Southern senators filibustered civil rights legislation precisely because they knew that if Black people in their states could vote freely, those senators would be ‘down the drain.’ Malcolm declared that ‘a ballot is like a bullet. You don’t throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.’ He urged African Americans to be ‘politically mature’ enough to understand that when ‘white people are evenly divided, and Black people have a bloc of votes of their own, it is left up to them to determine who’s going to sit in the White House.’

Malcolm didn’t stop at theory—he called for concrete organizing infrastructure. Speaking of Harlem, he announced: ‘We have to get everybody in Harlem registered, not as Democrats or Republicans, but registered as Independents. We’re going to organize a corps of brothers and sisters who, after this city is mapped out, they won’t leave one apartment-house door not knocked on.’ This wasn’t rejection of electoral politics—it was a demand for strategic, disciplined use of the ballot as a weapon for Black political power, built through systematic door-to-door organizing. Flateau’s work through the Coalition for community Empowerment Brooklyn embodied precisely this Malcolm X vision: treating the ballot as a bullet, deploying it with tactical precision through methodical voter registration and field operations in Central Brooklyn, and building the Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure necessary to make that political weapon effective.

This is the story of how one man—working as “chief political organizer and technician” for Brooklyn’s Coalition for Community Empowerment—transformed a borough’s political landscape and created a model for building sustainable Black political power through democratic organizing.

Part I: The CCE Chief Technician – Building Brooklyn Black Electoral Infrastructure (1981-2006)

The Colonized Landscape: Before the Coalition for Community Empowerment Brooklyn

To understand Flateau’s achievement, you must first understand the Brooklyn he encountered in the late 1970s. Despite having one of the largest Black populations in the nation, Brooklyn’s political representation bore little resemblance to its demographic reality. There was virtually no Black political power in Brooklyn. White Democrats controlled most elected positions, even in overwhelmingly Black neighborhoods. The party machinery—dominated by regular Democratic clubs closely tied to county leadership—selected candidates, controlled nominations, and maintained power through patronage and organizational discipline. It was this reality of electoral politics divorced from community control and Black self-determination that discouraged many African American activists from engaging in electoral organizing altogether.

Black Brooklynites voted, but their votes rarely translated into representation that reflected their communities or advanced their interests. This was not the Jim Crow disenfranchisement of the South, but a more subtle form of political exclusion: formal democracy without substantive power.

Al Vann Coalition for Community Empowerment co-founder was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1974. Vann—a former teacher and community activist—had come out of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school control movement and understood the structural problem. Vann realized that scattered individual victories were insufficient. What Black Brooklyn needed was infrastructure: an organization that could systematically identify, recruit, train, and elect a cohort of progressive Black leaders who would be accountable to the community rather than the party machine.

In 1981, Vann, together with Major Owens, founded the Coalition for Community Empowerment (CCE). But a coalition requires coordination, strategy, and the technical capacity to execute campaigns. For that, Vann turned to John Flateau.

The Chief Technician: What Flateau Actually Did

Flateau’s official title was “chief political organizer and technician” for the Coalition for Community Empowerment Brooklyn. That bureaucratic language obscured the revolutionary nature of his role. Flateau was building what amounted to a parallel political party—a progressive, Black-led insurgency operating within the Democratic Party structure but independent of its control. This tactical understanding—how to exist and excel within the existing system, the one that controls the daily lives of African Americans—is what John Flateau grasped and what many activists espousing revolutionary theory fail to understand: real power comes not from rejecting the system entirely, but from mastering its mechanics to deliver material gains—better schools, housing, jobs, and representation—that tangibly improve people’s daily lives.

His resume describes his CCE role with characteristic precision: “I was founding chief political organizer and technician for a growing cohort of progressive elected officials who politically liberated Central Brooklyn electoral districts from the party establishment, to be more representative of the communities and people they represented.”

“Politically liberated” is the key phrase. This was insurgent organizing disguised as electoral politics.

What did Flateau actually do as CCE’s chief technician? The work was systematic, granular, and relentlessly focused on building capacity:

1. Electoral Targeting and Analysis

Flateau began by treating Central Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure as a series of overlapping electoral districts—Assembly, State Senate, Congressional, City Council. Using demographic data and voting patterns, he identified districts where Black voters constituted a potential majority or substantial plurality but lacked representation. These became CCE’s battlegrounds.

He didn’t just count voters; he analyzed power relationships. Which incumbents were vulnerable? Where could progressive candidates challenge establishment figures? Which districts could be won with superior field operations even without institutional support? This was political science applied to community organizing.

2. Candidate Recruitment and Screening

The Coalition for Community Empowerment Brooklyn didn’t wait for candidates to emerge organically. Flateau and Vann systematically identified potential leaders—community activists, educators, union members, social workers—and recruited them to run for office. The CCE “screening” process was rigorous: candidates had to demonstrate commitment to progressive values, accountability to the community, and willingness to work collectively rather than as individual politicians.

This screening process was CCE’s secret weapon. While the regular Democratic organization nominated candidates based on loyalty to party bosses, CCE selected candidates based on their potential to serve community interests. The result was a cohort of elected officials who operated with unusual cohesion and strategic discipline.

3. Building the Ground Game: Field Operations Excellence

Flateau’s mastery of field operations—the nuts and bolts of campaigns—gave CCE candidates decisive advantages over establishment opponents who relied on name recognition and institutional support.

The field operation had multiple components that were essential for the building of Brooklyn black electoral infrastructure:

Petition Drives: New York’s ballot access requirements are notoriously complex and restrictive. Flateau became expert at organizing petition drives that not only secured ballot access but served as early organizing tools—identifying supporters, building volunteer lists, establishing neighborhood coordinators.

Voter Registration: CCE conducted targeted voter registration drives in housing projects, churches, barbershops, and community centers. This wasn’t scattershot registration but strategic targeting of likely progressive voters who would support CCE candidates.

Canvassing Operations: Flateau organized systematic door-to-door canvassing, training volunteers in persuasion techniques and message delivery. Canvassing served multiple purposes: identifying supporters, persuading undecideds, gathering intelligence on opposition messaging.

Direct Mail: Before digital organizing, direct mail was essential for reaching voters at scale. Flateau developed targeted direct mail programs that combined demographic analysis with message testing.

Get Out The Vote (GOTV): Election Day operations were Flateau’s specialty. He organized “pulling operations”—systematic efforts to identify supporters who hadn’t yet voted and transport them to polls. He established turnout monitoring systems and deployed troubleshooters to address problems in real time.

This ground game gave CCE candidates the ability to compete—and win—against opponents with superior name recognition and institutional backing. Flateau’s field operations could generate turnout differentials of 5-10 percentage points in targeted communities—often the margin of victory in competitive primaries.

4. Coalition Building and Labor Partnership

Flateau understood that CCE couldn’t win through the Black community alone. He built coalitions with organized labor—particularly District Council 37 (AFSCME), Local 1199 (SEIU), and other unions with substantial Black and Latino membership. These labor partnerships provided volunteers, funding, and institutional legitimacy.

The John Flateau Brooklyn political strategist resume highlights this explicitly: “In all campaigns and elections in which I have been involved, organized labor has played a crucial role.” Flateau wasn’t just using unions for resources; he was building a durable minority-labor coalition that could contest for power across multiple electoral levels.

He also built relationships with Latino organizations, recognizing that demographic change was making Black-Latino coalitions essential for progressive victories.

5. Training the Next Generation

Perhaps Flateau’s most important function was training. He didn’t hoard knowledge; he systematically taught emerging organizers the techniques of political campaigning. Campaign workers who started as volunteers under Flateau’s direction became managers, consultants, and eventually elected officials themselves.

This training extended beyond tactical skills to strategic thinking. Flateau taught organizers to think institutionally—to understand how power operates through party structures, how to build durable coalitions, how to plan campaigns years in advance rather than months.

Hakeem Jeffries, Yvette Clarke, and Letitia James all learned electoral politics in the world Flateau created. His training ground was campaigns; his classroom was the field operation.

The CCE Victories: Systematically Expanding Black Representation

The results of Flateau’s organizing were transformative. Between 1982 and 2006, Brooklyn Black electoral infrastructure expanded as CCE-backed candidates won victory after victory:

1982 Flateau v. Anderson Redistricting Case: The Congressional Breakthrough

The landmark 1982 Flateau v. Anderson redistricting case (discussed in detail in Part III) created new congressional districts with Black pluralities. CCE immediately seized the opportunity, backing Major Owens and Ed Towns for Congress.

Flateau’s resume describes his role: “Politically organized six Assembly districts, and two state senate districts as underpinnings to carry congressional districts to victory through coordinated campaigns, especially via field operations, petitioning, canvassing, GOTV and direct mail. The CCE decided to back Owens and Towns for Congress. Flateau ran the coordinated ground game from below, as CCE chief technician.”

Bill Lynch and Bill Banks served as campaign managers for Owens and Towns, respectively. But Flateau built the infrastructure that made their victories possible—organizing “from below” to ensure that CCE’s progressive base turned out in decisive numbers.

State and Local Victories

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, CCE systematically won Brooklyn based State Senate seats, Assembly seats, City Council positions, and district leader positions. Each victory expanded CCE’s institutional power and demonstrated the effectiveness of the organizing model.

Roger Green’s Assembly victory in Fort Greene-Clinton Hill (1980), Clarence Norman’s in Crown Heights (1980), and subsequent victories by CCE-backed candidates transformed the composition of Brooklyn’s delegation. By the 1990s, CCE-aligned elected officials constituted a significant voting bloc in Albany (New York State capitol) and New York City Hall.

Beyond Brooklyn: Influencing Citywide and Statewide Elections

As CCE’s organizational capacity grew, its influence extended beyond Brooklyn. Flateau’s role in New York politics was vast: mayoral campaigns (David Dinkins 1989, 1993), gubernatorial campaigns (Hugh Carey 1974, Mario Cuomo 1982), and presidential campaigns (Jimmy Carter 1976, Jesse Jackson 1984 and 1988, Bill Clinton 1992 and 1996, Barack Obama 2008).

In each case, CCE’s ability to deliver substantial vote margins in Brooklyn made the coalition a sought-after partner for citywide, statewide, and national campaigns. This gave CCE leverage—the ability to demand commitments, extract concessions, and shape policy agendas.

The Intergenerational Transition: From CCE to the Black Brooklyn Legislators Coalition

By the mid-2000s, the first generation of CCE leaders—Al Vann, Major Owens, Ed Towns—were aging. The question became: could the infrastructure survive generational transition?

Flateau played a crucial role in this transition. He referred to it in his resume as a “relatively peaceful, intergenerational political transitioning from older guard (CCE), to a new, further expanded current generation of progressive Black elected officials, led by Congresswoman Yvette Clarke and Congressman Hakeem Jeffries.”

This transition wasn’t automatic or inevitable. Many political machines collapse when founding leaders depart, as personal relationships and patronage networks dissolve. But Flateau had built something more durable: an institutional infrastructure with trained operatives, established procedures, and a shared understanding of collective action.

The Black Brooklyn Legislators Coalition that succeeded CCE maintained the organizing approach Flateau had pioneered. And when Yvette Clarke ran to succeed her mother (and Major Owens) in Congress in 2006, and when Hakeem Jeffries ran to succeed Ed Towns in 2012, they did so with the infrastructure Flateau had built over three decades.

Part II: Campaign Management Mastery – Five Decades of Electoral Victories

While Flateau’s CCE role provided the foundation, his broader career as a campaign manager, consultant, and senior advisor demonstrated his mastery of every aspect of electoral politics. His resume lists campaigns spanning 50 years—from volunteering for Shirley Chisholm in 1968 to serving as a senior advisor to Letitia James in 2013.

David Dinkins 1989 Campaign: The Partnership with Bill Lynch

Flateau’s most significant campaign role came in the David Dinkins 1989 campaign for mayor and the subsequent 1993 mayoral race. Bill Lynch served as campaign manager; Flateau was campaign coordinator. Their division of labor reflected complementary strengths: Lynch handled overall strategy, media, coalition building, and candidate management; Flateau ran the ground game.

Flateau’s resume specifies his Dinkins campaign role: “Flateau ran the ground game citywide, petition operations (148,000 signatures in 1989 and 1993); targeting; phone and field canvassing; direct mail; grassroots fundraising as an organizing tool; election day planning and logistics; get out the vote pulling operations, turnout monitoring and exit polling; election day legal defense/voter protection; and preparing for post-election challenges.”

This wasn’t just Brooklyn organizing scaled up—it was building a citywide operation from scratch. The David Dinkins 1989 campaign victory—New York City’s first Black mayor—rested on the field operation Flateau constructed. His ability to deliver decisive turnout in Brooklyn, mobilize labor volunteers citywide, and execute complex Election Day logistics made the narrow victory possible.

Dinkins won by fewer than 50,000 votes. Flateau’s field operation likely provided the margin.

The Presidential Campaigns: From Jackson to Obama

Flateau’s involvement in presidential campaigns—particularly Jesse Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 efforts—demonstrated his ability to translate local organizing expertise to national campaigns.

In 1984, when the Democratic establishment backed Walter Mondale, CCE leadership decided to support Jesse Jackson’s insurgent campaign. Flateau’s resume: “They got more statewide petition signatures than the Mondale operation; ran a field and GOTV operation where Jackson made a strong showing in NYC; and produced the largest Jackson Delegates contingent in the nation at the 1984 San Francisco Dem. Nat’l Convention.”

The 1988 Jackson campaign was even more successful. With Flateau helping coordinate Brooklyn operations, Jackson won New York City—a stunning victory that demonstrated the viability of a Black candidate in a diverse urban electorate.

This Jackson success convinced Bill Lynch and others that a Black candidate could win the New York City mayoralty with the right coalition and infrastructure—the strategic insight that led directly to the Dinkins campaigns.

Flateau’s presidential campaign work continued through Bill Clinton (1992, 1996), Hillary Clinton (2008), and Barack Obama (2008), always in the role of coordinating Brooklyn field operations and ensuring robust turnout in Black communities.

The Congressional Campaigns: Building the Next Generation

Two of Flateau’s campaign management roles stand out for their significance in building the next generation of Black leadership:

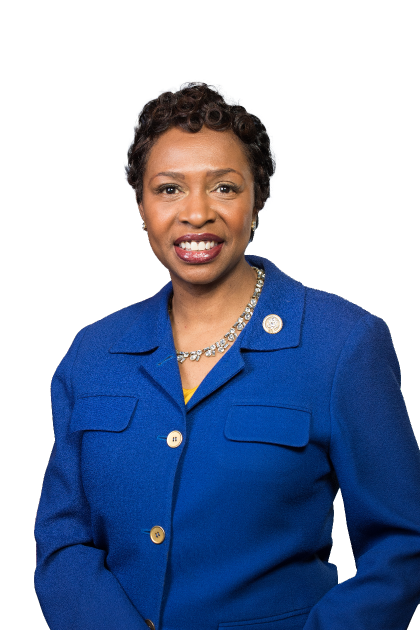

Yvette Clarke Campaign Manager for Congress (2006)

When Major Owens retired, multiple candidates competed to succeed him. Flateau served as the Yvette Clarke campaign manager in her run for Congress. Yvette Clarke is the daughter of Una Clarke, a pioneering African/Caribbean-American politician. Yvette succeeded her mother, Dr. Una S. T. Clarke, on the New York City Council, marking the first mother-daughter succession in the history of the council. The Clarke 2006 campaign for Congress was a campaign that required navigating complex ethnic politics (African American vs. African/Caribbean American constituencies), generational transition, and a competitive field.

Flateau’s resume notes he “managed all aspects of the campaign” and secured “major support from organized labor, 1199 SEIU, Emily’s List, et.al.” Clarke’s victory made her the second Caribbean-American woman in Congress and positioned her for eventual CBC leadership.

“Dr. Flateau helped to usher in an era of Black political empowerment in Central Brooklyn in the 1980s and 1990s that positively transformed the community and lives on to this day.”

Hakeem Jeffries, House Minority Leader

The Rise of Hakeem Jeffries

While Flateau’s resume doesn’t specify a formal role in Jeffries’s 2012 congressional campaign (he was by then winding down active campaign management), in personal conversations, he told me about the emergence of Hakeem Jeffries through the Brooklyn infrastructure and considered Jeffries to be a product of his decades’ long infrastructure building work. Jeffries himself acknowledged this in his statement after Flateau’s death: “Dr. Flateau helped to usher in an era of Black political empowerment in Central Brooklyn in the 1980s and 1990s that positively transformed the community and lives on to this day.”

The infrastructure Flateau built—CCE’s networks, trained operatives, institutional relationships, field operation techniques—became the foundation for Jeffries’s rise.

Letitia James: From Public Advocate to Attorney General

John Flateau’s work as the senior campaign advisor to Letitia James in her 2013 Public Advocate campaign represents his final major campaign role before his appointment as NYC Elections Commissioner (which required him to cease campaign consulting).

James’s victory was historic: she became the “first woman of color ever elected to citywide office in NYC.” Flateau’s resume describes his role as the senior campaign advisor to Letitia James: “Strategic advice on setting up citywide field operations, electoral and demographic targeting, polling analysis, petition operations, visibility, phone and field canvassing; targeted direct mail; election day planning and logistics; get out the vote pulling operations; election day legal defense/voter protection; and preparing for post-election challenges.”

This was the full Flateau playbook, refined over four decades, applied to a citywide campaign. James’s subsequent election as New York Attorney General in 2018—the first Black woman to hold that position—built on the citywide infrastructure and name recognition her Public Advocate tenure provided.

“We have so many elected officials who look like me and all of you in this room because of John Flateau’s brilliance.”

New York State Attorney General Letitia james

Years later, reflecting on Flateau’s legacy after his death, James acknowledged the profound impact of his work: “We have so many elected officials who look like me and all of you in this room because of John Flateau’s brilliance.” She praised him as someone who “was a statistician and someone who was strategic in his politics. He believed in democracy and the fundamental right to vote. We should honor him for all he has done for Brooklyn and the City and State of New York.” James noted that Flateau and his colleagues “challenged district maps and the reapportionment here in New York City” and were “successful in creating more council and assembly districts, particularly in central Brooklyn and communities of color.”

The Campaign Technician’s Toolkit

Across these campaigns, Flateau deployed a consistent set of techniques that constituted his “toolkit” for winning elections:

Petition Operations: Flateau was a master of New York’s complex ballot access petition requirements. He understood that petition drives served multiple functions—not just ballot access but early volunteer recruitment, supporter identification, and demonstration of organizational capacity. Among New York political operatives, it was well known that an opposing campaign could keep or knock a candidate off the ballot by using something as mundane as a misplaced signature to disqualify a candidate’s petitions—making Flateau’s technical expertise in this arcane but critical area an invaluable asset that could mean the difference between a candidate appearing on the ballot or being eliminated before voters ever had a chance to weigh in.

Targeting: Using demographic analysis, voting history, and local knowledge, Flateau identified high-value precincts where superior field operations could generate decisive margins. He was a master at this, using a slide rule and calculator before the era of personal computers and mobile phones. This targeting allowed efficient resource allocation—concentrating volunteers and resources where they would have maximum impact.

Field Canvassing: Flateau understood that personal contact remained the most effective form of persuasion. He organized systematic door-to-door canvassing, training volunteers in scripting, persuasion techniques, and data collection.

Direct Mail: Before digital organizing, direct mail was essential for voter contact at scale. Flateau developed targeted mail programs that combined demographic segmentation with message testing.

GOTV Excellence: Flateau’s Election Day operations were legendary. He organized systematic “pulling operations”—identifying supporters who hadn’t voted and ensuring they got to the polls. He established real-time turnout monitoring and rapid response systems. On election day, Flateau could be found in the campaign’s back room crunching the numbers.

Legal Defense/Voter Protection: Flateau understood that Election Day problems—polling place issues, voter challenges, ballot shortages—could suppress turnout. He organized legal defense teams and voter protection operations to address problems immediately.

This toolkit wasn’t revolutionary—these are standard campaign techniques. What made Flateau exceptional was execution: the systematic thoroughness, attention to detail, and organizational discipline he brought to every campaign.

Part III: The Redistricting and Voting Rights Champion – Expanding Black Political Representation Through Law

While Flateau’s CCE organizing and campaign management get more attention, his work on redistricting and voting rights may be his most enduring contribution. Redistricting is the unglamorous work of drawing electoral district lines—but it fundamentally shapes who can be elected and which communities can exercise power.

Flateau understood this intuitively. Before CCE could win elections, it needed districts where Black voters constituted majorities or substantial pluralities. This required fighting legal battles and participating in redistricting processes.

Flateau v. Anderson (1982): The Landmark Case

The most significant redistricting battle bore Flateau’s name as lead plaintiff: Flateau v. Anderson (1982).

Following the 1980 Census, New York State lost five congressional seats due to population decline. The state legislature needed to redistrict—redrawing congressional and state legislative lines to reflect population shifts. But the Republican-controlled State Senate wanted to delay redistricting until 1984, allowing the existing (unconstitutional) districts to be used in the 1982 elections.

This delay wasn’t accidental—it was strategic. New redistricting based on 1980 Census data would increase Black and Latino representation. The Republican Senate wanted to preserve white suburban Republican districts for as long as possible.

Flateau, working with the New York State Black and Hispanic Legislative Caucus (where he served as Executive Director), filed suit challenging the delay. The federal case—Flateau v. Anderson—argued that using outdated district lines violated the Equal Protection Clause (one person, one vote) and the Voting Rights Act.

The case was decided swiftly. The federal district court ruled in Flateau’s favor, ordering New York to complete redistricting immediately for the 1982 elections. This judicial intervention forced the creation of new congressional and state legislative districts with Black and Latino pluralities.

The immediate impact was dramatic: Major Owens and Ed Towns won newly created congressional seats in Brooklyn. Additional State Senate and Assembly seats became winnable for Black and Latino candidates.

But the long-term impact was even more significant. Flateau v. Anderson established judicial precedent that population-based redistricting couldn’t be indefinitely delayed—creating legal tools that subsequent voting rights advocates would deploy in other states and other redistricting cycles.

Jeff Wice, a redistricting expert, called Flateau “a voting rights pioneer” and noted that Flateau v. Anderson was “a landmark 1982 federal court case that successfully challenged New York’s delay in redistricting the state legislature.”

The Legal Defense Fund’s statement after Flateau’s death emphasized this contribution: “LDF filed an amicus brief in Flateau v. Anderson (1982), in which Dr. Flateau was a plaintiff in the case to advocate for fair redistricting lines in congressional representation.”

The NYC Council Redistricting (1990-1991)

[Editor’s note – I directed the CSS Districting Project in 1990 and 1991 to monitor and impact the work of the New York City Districting Commission to redistrict the New York City Council. The Council had been expanded in size in response to a lawsuit that challenged the constitutionality of the New York City Board of Estimate, an unelected body that controlled the New York City budget and made the most significant and consequential decisions. We brought on John Flateau Brooklyn political strategistI to serve as our political and geographic consultant. In this capacity, Flateau took the lead in helping us determine the extent and type of election history data needed for the project. He assisted further with identifying the specific neighborhoods and communities to be assigned to the proposed new councilmanic districts in our alternative plan and in determining where to draw the boundaries of those proposed districts.

Following David Dinkins’s 1989 election as mayor, New York City undertook a major restructuring of its government, including expansion and redistricting of the City Council. The Council grew from 35 to 51 seats—creating significant opportunities for increased Black and Latino representation.

Flateau played a key role in this redistricting process, serving on multiple redistricting commissions and working closely with me as the political and geographic consultant to the CSS redistricting project.

This NYC redistricting was consequential because it created districts that subsequent generations of Black and Latino politicians would represent. It is from one of these new districts that Una Clarke was elected to the New York City Council, to be subsequently succeeded by her daughter, Yvette Clarke, who went on to be elected to Congress (in a campaign run by John Flateau), and currently serves a Chair of the Congressional Black Caucus. The City Council elected in the early 1990s reflected the city’s diversity in unprecedented ways—a direct result of the redistricting Flateau helped shape.

Favors v. Cuomo (2012): The Next Generation

Flateau’s redistricting work continued into the 2010s. He served as an advisor in Favors v. Cuomo (2012), another major redistricting case that shaped New York’s congressional districts after the 2010 Census.

This case was particularly significant because it affected districts that Hakeem Jeffries and others would represent. Flateau’s decades of experience made him a sought-after expert in these complex legal and political battles.

His resume notes: “Plaintiff, researcher in landmark redistricting and voting rights cases (Flateau v. Anderson, Andrews v. Koch; et.al.) that increased New York State and City minority political representation.”

The Redistricting Expertise: Combining Law, Demographics, and Politics

Flateau’s redistricting work required synthesizing multiple forms of expertise:

Legal Knowledge: Understanding the Voting Rights Act, Equal Protection Clause, state constitutional requirements, and case law. Redistricting operates within complex legal constraints—Flateau mastered this legal architecture.

Demographic Analysis: Reading Census data, analyzing population distributions, understanding racial and ethnic demographics. Effective redistricting requires sophisticated data analysis.

Political Strategy: Knowing which communities could be mobilized, which coalitions were viable, which district configurations would maximize representation. Demographics alone don’t determine political outcomes—organizing does.

Flateau combined all three. He understood law, data, and politics—and how they intersected in the technical work of drawing district lines.

The Institutional Roles: Building Redistricting Capacity

Beyond specific cases, Flateau held numerous institutional positions related to redistricting and voting rights:

- General Consultant, CSS redistricting project, 1991

- Commissioner, New York City Districting Commission

- Member, NYS Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment

- Chairman, US Census Advisory Committee on the African American Population

- National Steering Committee, Census Information Centers

- Co-Chair, NYC Black Advisory Committee, Census 2000

- Director, US Census Information Center at Medgar Evers College

These weren’t honorary positions—they were operational roles where Flateau helped shape how census data was collected, analyzed, and used for redistricting.

His academic role as director of the US Census Information Center at Medgar Evers College gave him access to census data and demographic analysis that informed his redistricting work. He literally wrote the book on this subject: his PhD dissertation, “Black Brooklyn: The Politics of Ethnicity, Class and Gender,” provided deep analysis of how census data, redistricting, and organizing intersected to expand Black political representation.

Part IV: The Mentorship and Legacy – Three National Leaders

The most visible measure of Flateau’s impact is the leaders he helped produce: Hakeem Jeffries, Yvette Clarke, and Letitia James—three national figures who came through the infrastructure Flateau built.

Hakeem Jeffries: From Brooklyn Organizing to House Democratic Leader

Hakeem Jeffries’s trajectory from Brooklyn Assemblymember to U.S. House Democratic Leader—the highest position ever held by a Black elected official in Congress—is impossible to understand without the infrastructure Flateau built.

Jeffries didn’t emerge from nowhere. He came through the CCE organizing tradition, learning electoral politics in the world Al Vann and John Flateau created. While Flateau didn’t directly manage Jeffries’s campaigns (he was serving as Elections Commissioner by then), the infrastructure, techniques, and networks Flateau built over three decades made Jeffries’s rise possible.

Jeffries’s own words after Flateau’s death acknowledge this debt: “An important part of a powerful movement led by the late, great Al Vann, Dr. Flateau helped to usher in an era of Black political empowerment in Central Brooklyn in the 1980s and 1990s that positively transformed the community and lives on to this day.”

Jeffries understands that his position as House Democratic Leader rests on foundation Flateau laid—the congressional seat created through Flateau v. Anderson redistricting, won initially by Ed Towns through CCE organizing, and passed to Jeffries through the intergenerational transition Flateau helped engineer.

This is how sustainable political power is built—not through individual charisma or viral moments, but through patient infrastructure development that produces leader after leader, generation after generation.

Yvette Clarke: African/Caribbean-American Political Power

Yvette Clarke’s path to Congress and CBC leadership similarly depended on Flateau’s work. As campaign manager for her 2006 congressional race, Flateau directly shaped her victory. But more broadly, Clarke’s political career developed within the CCE infrastructure that prioritized expanding representation for Brooklyn’s growing African/Caribbean-American community.

The congressional district Clarke represents was created through the redistricting battles Flateau fought. He understood and knew that terrain at the block, voter tabulation district, census tract, assembly district, city council district, and state senate levels. The organizing techniques she used came from Flateau’s playbook. The labor coalition that supported her campaign reflected relationships Flateau had built over decades.

Clarke’s election was historic—continuing the African/Caribbean-American representation that Una Clarke (her mother) had pioneered on the City Council. Yvette Clarke emerged as successor to her mother’s legacy. And Una Clarke’s political rise was a direct result of the 1991 expansion of the New York City Council from 35 to 51 seats and the city advocacy, spearheaded by the CSS redistricting project (which I led and John Flateau served as the politcal and geographic consultant). This represented another form of power-building: ensuring that Brooklyn’s ethnic diversity was reflected in its political leadership.

Letitia James: From Brooklyn to Statewide Power

Letitia James’s trajectory—from working as counsel to Al Vann (Coalition for Community Empowerment Brooklyn co-founder), to City Council, to Public Advocate, to Attorney General—demonstrates the power of the infrastructure Flateau helped build.

James herself has acknowledged her debt to the CCE tradition. She worked directly for Al Vann and Roger Green (both CCE leaders) before running for office. When she ran for Public Advocate in 2013, Flateau served as senior campaign advisor—applying his decades of experience to her citywide campaign.

James’s subsequent election as New York Attorney General in 2018 made her the first Black woman to hold that position and positioned her as a potential future governor. This trajectory—from Brooklyn organizing to statewide power—exemplifies what Flateau’s infrastructure made possible.

The Pattern: Infrastructure Produces Leaders

What unites Jeffries, Clarke, and James is not just that they came from Brooklyn, but that they came through a particular organizing tradition—one that Flateau spent four decades building and refining.

They learned electoral politics in environments Flateau created. They used techniques Flateau pioneered. They benefited from districts Flateau helped create, coalitions he helped build, and institutional relationships he cultivated.

This is the opposite of charismatic leadership or individual brilliance. It’s institutional capacity—the accumulated knowledge, relationships, and organizational strength that allows communities to produce leader after leader, generation after generation.

Part V: The Scholar-Practitioner – Bridging Academia and Organizing

Flateau’s career uniquely combined practical political organizing with academic scholarship—a rare synthesis that enhanced both dimensions of his work.

The Academic Career: Medgar Evers College

Flateau joined Medgar Evers College’s faculty in 1994 and spent three decades teaching public administration and political science. He held multiple leadership roles:

- Professor of Public Administration and Political Science

- Chair, Department of Public Administration

- Dean, School of Business

- Dean of Institutional Advancement & Government Affairs

- Senior Fellow and Executive Director, DuBois Bunche Center for Public Policy

- Director, US Census Information Center

This wasn’t a traditional academic career focused solely on research and publishing. Flateau used his academic platform to advance the work he was doing in the field—training students who would become the next generation of organizers and public servants.

His teaching reflected his organizing experience. Colleagues and former students remembered him as someone who brought real-world political knowledge into the classroom, teaching students not just theory but the practical mechanics of campaigns, governance, and public administration.

The Scholarship: “Black Brooklyn”

Flateau’s PhD dissertation—”Black Brooklyn: The Politics of Ethnicity, Class and Gender“—is considered among the best in its genre. This wasn’t abstract academic work divorced from practice; it was deep analysis of the very organizing work Flateau was doing.

The dissertation examined how census data, redistricting, voting rights litigation, and community organizing intersected to expand Black political representation in Brooklyn. It documented the CCE organizing tradition from the inside, combining participant observation with scholarly analysis.

This scholarship informed his practice. Flateau understood the theoretical foundations of political power—how demography, institutions, and organizing interact to produce political outcomes. This theoretical sophistication made him a more effective practitioner.

The Bridge: Practitioner-Scholar

The practitioner-scholar model Flateau embodied is increasingly rare. Too often, academics study politics without doing it; activists organize without analyzing it. Flateau did both simultaneously, using each dimension to enhance the other.

His academic role gave him access to data, analytical tools, and institutional resources that strengthened his organizing work. His organizing experience gave his scholarship authenticity and practical relevance that pure academic work often lacks.

Students at Medgar Evers College learned from someone who wasn’t just teaching about campaigns—he was running them. His courses on campaign management, public administration, and political science drew on five decades of practical experience. There is no substitute for this kind of experience. I know first hand, having been a student enrolled in his Campaign Management course at the Graduate School of Political Management.

Training the Next Generation: The Classroom as Organizing Space

Perhaps Flateau’s most important academic contribution was training the next generation of public administrators, organizers, and political professionals. Medgar Evers College—a predominantly Black institution with heavy African/Caribbean-American enrollment—gave Flateau access to exactly the students who would become Brooklyn’s next generation of civic leaders.

His teaching wasn’t just transmitting knowledge; it was political education in the deepest sense—helping students understand how power operates and how to build it in their communities.

Former students who went on to work in government, nonprofits, and political campaigns carried Flateau’s lessons with them. This pedagogical legacy multiplied his impact far beyond the campaigns he personally managed.

Part VI: The Final Act – NYC Elections Commissioner and Institutional Leadership

Flateau’s appointment as Commissioner of the New York City Board of Elections in 2014 represented both a culmination and a transition. The position—which required him to cease active campaign consulting—gave him institutional authority over the very electoral processes he had spent decades mastering.

The Elections Commissioner Role

As Elections Commissioner, Flateau was responsible for election administration across New York City’s five boroughs—4.2 million registered voters, multiple concurrent elections, complex voting technologies, and intense political scrutiny.

This wasn’t a figurehead position. Flateau brought his decades of campaign experience to the administrative side of elections—understanding from the inside how registration systems, polling place operations, and ballot counting procedures affected electoral outcomes.

His knowledge of field operations made him particularly attuned to problems voters encountered—long lines, inadequate polling places, registration issues. He had spent decades trying to maximize turnout; now he was responsible for ensuring the administrative machinery actually facilitated participation.

The Institutional Roles: Building Civic Infrastructure

Beyond elections administration, Flateau continued serving in multiple institutional roles:

- Member, NYS Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment

- Member, Elections and Redistricting Network, National Conference of State Legislatures

- Member, American Association of Political Consultants

- Member, National Conference of Black Political Scientists

- Senior Advisor, NYS Coalition of Black Elected Officials

These weren’t honorary memberships—they were operational roles where Flateau continued shaping voting rights, redistricting, and civic participation policy at state and national levels.

The Community Leader: Beyond Politics

Flateau’s community engagement extended beyond electoral politics to civic infrastructure:

- Board Member, Bridge Street AWME Church (one of Brooklyn’s oldest Black churches)

- Founder and leader of multiple community development corporations

- Chairman, Board of Trustees, Community School Board 16

- Life member, NAACP

- Active member, African Atlantic Genealogical Society

This civic engagement reflected Flateau’s understanding that political power requires community infrastructure—churches, schools, civic organizations, cultural institutions. Electoral organizing doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it emerges from strong communities with dense networks of institutions.

Part VII: The Democratic Organizing Model – Why Flateau’s Approach Matters

In an era when many activists question whether electoral politics can produce transformative change, Flateau’s life offers a powerful counterargument. He spent 50 years building Black political power through democratic organizing—voter registration, coalition-building, field operations, redistricting—and produced tangible, measurable results.

Not Revolutionary Theoretical Politics, But Democratic Revolutionary Infrastructure Building

The significance of Flateau’s work lies precisely in its method: he built Black political power through active democratic participation, not revolutionary transformation. He worked within the American electoral system, mastering its rules and leveraging its opportunities to expand representation, shift power relationships, and to transform it from within.

This approach frustrates those who view electoral politics as inherently insufficient or compromised. But Flateau’s results speak for themselves:

- Created two congressional seats through redistricting litigation (Flateau v. Anderson)

- Helped elect multiple members of Congress (Owens, Towns, Clarke, Jeffries)

- Contributed to the election of New York City’s first Black mayor (Dinkins)

- Helped produce New York’s first Black woman Attorney General (James)

- Expanded Black representation in state legislature, City Council, and other elected bodies

- Built infrastructure that produced three national political leaders

- Used voting rights and redistricting to create opportunities for African American,including African Caribbean, voters to elect candidates of their choosing at all levels of government.

This is what patient, systematic democratic organizing can achieve—not overnight, but over decades.

The CCE Model: What Made It Work

Several factors explain CCE’s success and Flateau’s effectiveness:

1. Institutional Infrastructure, Not Individual Leaders

CCE wasn’t built around individual charisma or personality cults. It was institutional infrastructure—organizational procedures, training programs, field operation techniques, coalition relationships. This infrastructure outlasted individual leaders and survived generational transitions.

2. Technical Excellence in Field Operations

Flateau’s mastery of campaign mechanics—petitioning, canvassing, GOTV operations—gave CCE candidates decisive advantages. Superior execution of unglamorous technical work won elections.

3. Long-Term Strategic Planning

CCE thought in decades, not election cycles. The decision to invest in redistricting litigation in 1981-1982 was strategic planning for elections that wouldn’t occur until 1982 and beyond. The training of young organizers in the 1980s produced leaders in the 2000s and 2010s.

4. Coalition Building

CCE understood that Black political power required coalitions—with labor unions, Latino organizations, white progressives. Flateau built these coalitions systematically, maintaining relationships across multiple election cycles.

5. Integration of Electoral and Governing Strategies

CCE didn’t just elect officials; it held them accountable and coordinated their legislative activity. The State Black and Hispanic Legislative Caucus that Flateau directed wasn’t just a collection of individuals; it was a coordinated bloc advancing shared policy goals.

Why This Model Is Difficult to Replicate

Despite CCE’s success, few cities have replicated the model. Why?

It requires patient, long-term investment. Building infrastructure takes years before producing visible results. Funders and activists often prioritize immediate wins over long-term capacity building.

It requires technical expertise. Flateau’s mastery of campaign mechanics, redistricting law, district drawing/creation, and demographic analysis took decades to develop. This expertise isn’t easily transferred.

It requires institutional stability. CCE benefited from Al Vann’s 32 years in the State Assembly, providing stable leadership and institutional continuity. Few organizations have such stability.

It requires subordinating individual ambition to collective strategy. CCE demanded that elected officials operate collectively rather than as individual political entrepreneurs. This is culturally difficult in American politics.

Nevertheless, the CCE model demonstrates what’s possible when organizing is systematic, patient, and strategically sophisticated.

The Contemporary Relevance

As American democracy faces challenges—voter suppression, gerrymandering, declining civic participation, political polarization—Flateau’s work offers lessons:

Democratic infrastructure matters. Viral moments and charismatic leaders can’t substitute for patient organizing that builds lasting capacity.

Technical excellence wins. Superior field operations, better data analysis, more effective GOTV efforts—these tactical advantages determine electoral outcomes.

Coalitions are essential. No community can build power in isolation. Multi-racial and multi-ethnic, labor-community coalitions remain necessary for progressive victories.

Redistricting is power. The unglamorous work of drawing district lines fundamentally shapes who can exercise political power. Participating in redistricting processes is essential.

Train the next generation. Flateau’s teaching at Medgar Evers College and training of campaign workers ensured his knowledge transferred to subsequent generations. Without deliberate training, organizing knowledge dies with individuals.

Conclusion: The Invisible Architect’s Enduring Legacy

John Flateau passed away on December 30, 2023, having built Brooklyn’s Black political infrastructure over five decades. He didn’t become famous. He wasn’t on television or social media. He built the machinery that put others in the spotlight.

But his legacy is everywhere in Brooklyn’s political landscape:

When Hakeem Jeffries convenes House Democrats as their leader, he stands on infrastructure Flateau built—the congressional district created through Flateau v. Anderson, the organizing techniques Flateau pioneered, the CCE tradition Flateau sustained.

When Yvette Clarke chairs the Congressional Black Caucus, she leads from a position Flateau helped her win—as campaign manager who applied five decades of experience to her 2006 campaign.

When Letitia James pursues accountability as New York Attorney General, she wields power that traces back to the Brooklyn organizing tradition Flateau helped create—working for Al Vann, learning electoral politics in CCE’s world, running with Flateau’s advice.

This is how sustainable political power is built—not through individual brilliance or revolutionary fervor, but through patient, systematic organizing that creates infrastructure capable of producing leader after leader, generation after generation.

Flateau’s approach—democratic organizing focused on voter registration, field operations, coalition-building, redistricting, and technical excellence—offers a model for building Black political power within American democracy. It requires patience, technical skill, strategic sophistication, and long-term commitment. But the results speak for themselves.

The invisible architect is gone. But the machinery he built continues producing leaders who shape American politics at the highest levels. That is legacy.

Epilogue: “Holding Up the Banner for Medgar”

In October 2023—just two months before his death—the Vannguard Independent Democratic Association (VIDA) honored Flateau with the Dr. Albert Vann Legacy Award. When Medgar Evers College President Patricia Ramsey sent him a congratulatory email, Flateau replied simply:

“Thank you President Ramsey! Holding up the banner for Medgar!-John.”

That phrase—”holding up the banner”—captures Flateau’s sense of his mission. He understood himself as carrying forward a legacy of struggle, organizing, and community service that extended back through generations. He was holding up the banner for Medgar Evers, for Malcolm X, for Rosa Parks, for all those who had fought for Black political power and democratic participation.

And he was passing that banner to the next generation—the students he taught, the organizers he trained, the leaders he helped elect.

On Wednesday, January 10, 2024, hundreds gathered at Bridge Street AWME Church in Brooklyn for Flateau’s funeral. Elected officials spoke. Former students testified. Family members mourned. The tributes were heartfelt and deserved.

But perhaps the truest tribute was the elected and nationally known leaders whose careers Flateau helped make possible: The New York State Attorney General, Letitia James; the House Minority leader, Hakeem Jeffries, the current chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, Yvette Clarke. These leaders were among the volumes of leaders, attorneys, and others who paid tribute to John Flateau. They were all recognizing the debt they owed to the invisible architect who had built the infrastructure that helped to make their leadership possible.

The banner is being held high.

Dr. John Louis Flateau (February 24, 1950 – December 30, 2023)

Rest in Power, Brother, Leader.

Acknowledgments

This article draws on my personal relationship with John Flateau, his political resume that he shared with me a few years ago, obituaries, tributes from elected officials, academic biographical materials, and legal documents. Additional research was conducted on the Coalition for Community Empowerment, Flateau v. Anderson case law, and Brooklyn political history.

About BlackPolitics.org: This article is part of our Electoral Politics current—documenting how Black political power has been built through democratic organizing, voter registration, coalition-building, and institutional development. While we also document revolutionary Black nationalism and other currents, this article focuses specifically on the democratic organizing tradition that produced leaders like John Flateau.

Selwyn Carter

January 31, 2026