Florida State Senators Tony Hill and Kendrick Meek Lead March on Tallahassee

The March on Tallahassee turned a Capitol sit-in into a mass movement for equity, labor, and Black voter power.

Today, Florida politics is dominated by Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis — figures who’ve reshaped the state into a national proving ground for hardline conservatism, voter suppression tactics, and culture war governance. From redistricting battles to book bans, Florida has become a bellwether for rollback politics — where executive power is wielded to erase equity gains and silence dissent.

But rewind to the year 2000, and the landscape looked very different. Jeb Bush was governor, and his “One Florida” initiative had just gutted affirmative action by executive order. In response, Black legislators staged a sit-in at the Capitol — refusing to leave until they were heard. That act of defiance sparked the March on Tallahassee, one of the largest civil rights mobilizations in Florida history. It was a moment when labor, students, and churches came together to defend equity — and to build the civic infrastructure that would carry Florida’s Black communities into the ballot box and beyond.

🔥 A Sit-In That Sparked a Movement

In this post, you will discover how the March on Tallahassee in 2000—sparked by a Capitol sit-in—mobilized labor, students, and churches across Florida to defend affirmative action and fuel Black voter turnout in a pivotal election year. On January 18, 2000, Florida State senators Tony Hill and Kendrick Meek staged a sit-in inside the office of Florida Governor, Jeb Bush. They refused to leave until Bush agreed to meet with Black legislators about his “One Florida” initiative — a sweeping executive order that dismantled race-based affirmative action in university admissions and state contracting.

Bush refused. Hill and Meek stayed for 25 hours. That act of legislative defiance ignited a statewide backlash — one that would culminate in one of the largest civil rights mobilizations in Florida history.

📅 The March on Tallahassee: Scale, Strategy, and Symbolism

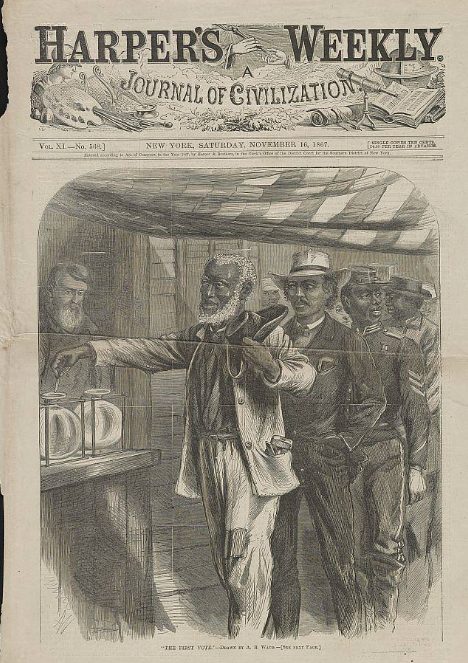

On March 7, 2000, the opening day of Florida’s legislative session and the 35th anniversary of Bloody Sunday in Selma, between 45,000 and 80,000 people converged on the Capitol in Tallahassee. The March on Tallahassee was a direct response to Bush’s refusal to engage — and a mass assertion of Black political power.

I was in Tallahassee for the March. As national AFL-CIO politcal campaign director for the Southern region at the time, I led our field mobilization response on the ground — coordinating union turnout, messaging, and logistical support. It was a moment of clarity: protest, policy, and electoral strategy converged.

🧩 Who Mobilized — and Why It Mattered

The March drew strength from a broad coalition:

- Labor unions: Led by Tony Hill, then Secretary-Treasurer of the Florida AFL-CIO, labor played a central role. Longshoremen, electrical workers, and public sector unions marched with banners and handmade signs. South Florida locals chartered 50 buses. The AFL-CIO’s “Labor 2000” strategy framed the protest as part of a national working families agenda.

- Students: Thousands from Florida A&M, Florida State, Bethune-Cookman, and other colleges marched. Many had been activated by the sit-in and organized teach-ins, voter registration drives, and campus rallies.

- Clergy and civil rights leaders: Rev. Jesse Jackson, NAACP President Kweisi Mfume, and other national figures joined the march. Churches across Florida mobilized transportation and turnout — linking spiritual leadership to civic resistance.

- Grassroots organizations: NAACP, Urban League, and local civic groups formed the Coalition of Conscience, coordinating logistics, messaging, and media outreach.

🏛️ Jeb Bush’s Response — and the Political Fallout

Governor Bush defended “One Florida” as race-neutral and merit-based, offering guaranteed university admission to the top 20% of each high school class. But his refusal to meet with Black legislators — and his dismissal of the March — alienated many voters and drew national criticism.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights later cited Florida’s policies as contributing to systemic disenfranchisement. Bush’s posture became a flashpoint in the 2000 presidential election — especially after the recount crisis.

🗳️ From Protest to the Polls: Electoral Impact

The March on Tallahassee helped energize Black voter turnout for Al Gore in Florida’s 2000 presidential election — especially among union households, HBCU students, and church-based networks mobilized by the sit-in.

Despite a surge in engagement across Florida — including mass mobilization through Labor 2000, church networks, and student-led organizing — the presidential election was ultimately decided by a mere 537 votes. As a national AFL-CIO staffer and recount monitor, I was in Tallahassee for the March and led our field response on the ground. Later in November, the size of the AL Gore mobilization in Miami Beach the night before the election was mind boggling. Tens of thousands flooded the streets. Stevie Wonder, Jon Bon Jovi, and Deborah Cox performed live on stage, and Al Gore spoke to the crowd with his back against the ocean sometime around 2:00am. The energy was electric, and the crowd left that final rally convinced that we would win Florida and the election. But the Supreme Court’s intervention stopped the count and handed the presidency to George W. Bush. The March on Tallahassee wasn’t just a protest — it was a blueprint for resistance, and a warning about the fragility of our democratic infrastructure.

🧭 Legacy and Strategic Infrastructure

- Institutional memory: The March seeded new organizing models — blending legislative protest, labor mobilization, and electoral strategy

- Leadership pipeline: Kendrick Meek went on to serve in Congress; Tony Hill became a senior advisor and movement strategist

- Civic continuity: The Coalition of Conscience laid groundwork for future campaigns around redistricting, education equity, and voting rights

November 11, 2025