Former SRC executive director, Steve Suitts, has long been one of the South’s most incisive chroniclers — documenting the unfinished struggle for racial justice with clarity, courage, and historical depth. In this paper, originally presented at the University of Florida, Suitts reflects on the Southern Regional Council’s work to expand democracy and build Black political power across the South between 1977 and 1994. From redistricting to education reform, the Council helped shape the civic infrastructure we inherit today.

I had the privilege of working at the Council in the 1990s under Steve’s leadership. His strategic clarity and moral urgency shaped not only the Council’s legacy, but my own understanding of what it means to build democratic infrastructure in the South. Today, Steve continues to guide our work as a member of the Black Politics Advisory Council — helping us recover, preserve, and teach the full spectrum of Black political life.

This paper is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand how democratic and electoral infrastructure was built — not just protested for — in the post–civil rights era. It complements our pillar post on the Southern Regional Council and deepens our archive of Black political history.

We publish it here in full, with maps and appendices, as part of the Southern Civic Memory Institute — our initiative to preserve and make searchable the untold stories of Black electoral and grassroots movements, especially those active from the 1970s through the 1990s, and to document related efforts beyond that era.

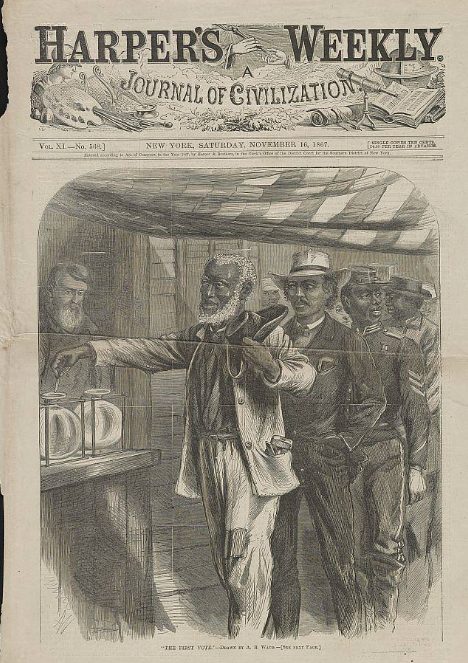

These decades saw the rise of transformative campaigns, institutions, and coalitions that shaped Black political power. Yet much of this history remains underrepresented online. While the 1960s civil rights era has received extensive digital attention, the movements that followed — often more localized, strategic, and coalition-driven — remain less visible in the public record. BlackPolitics.org is committed to recovering and preserving these stories, ensuring they are accessible to future generations.

The Southern Regional Council: Building Black Political Power and Expanding Democracy Across the South, 1977–1994

Summary of Key Findings – SRC and:

By Steve Suitts

🗳️Political Democracy

- Vote Dilution: The council helped more than 500 African American community leaders challenge unfair voting schemes through litigation, technical support, and public education.

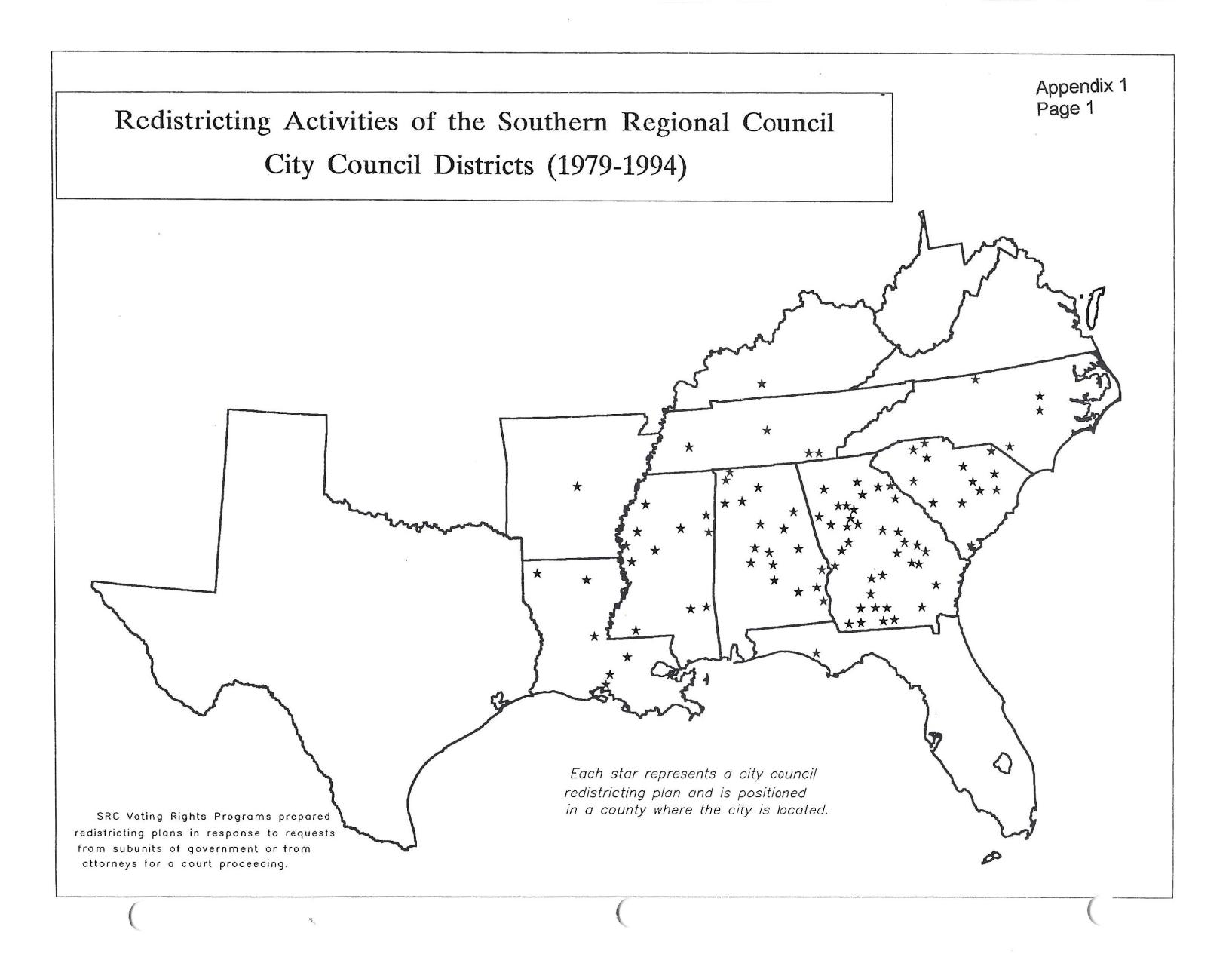

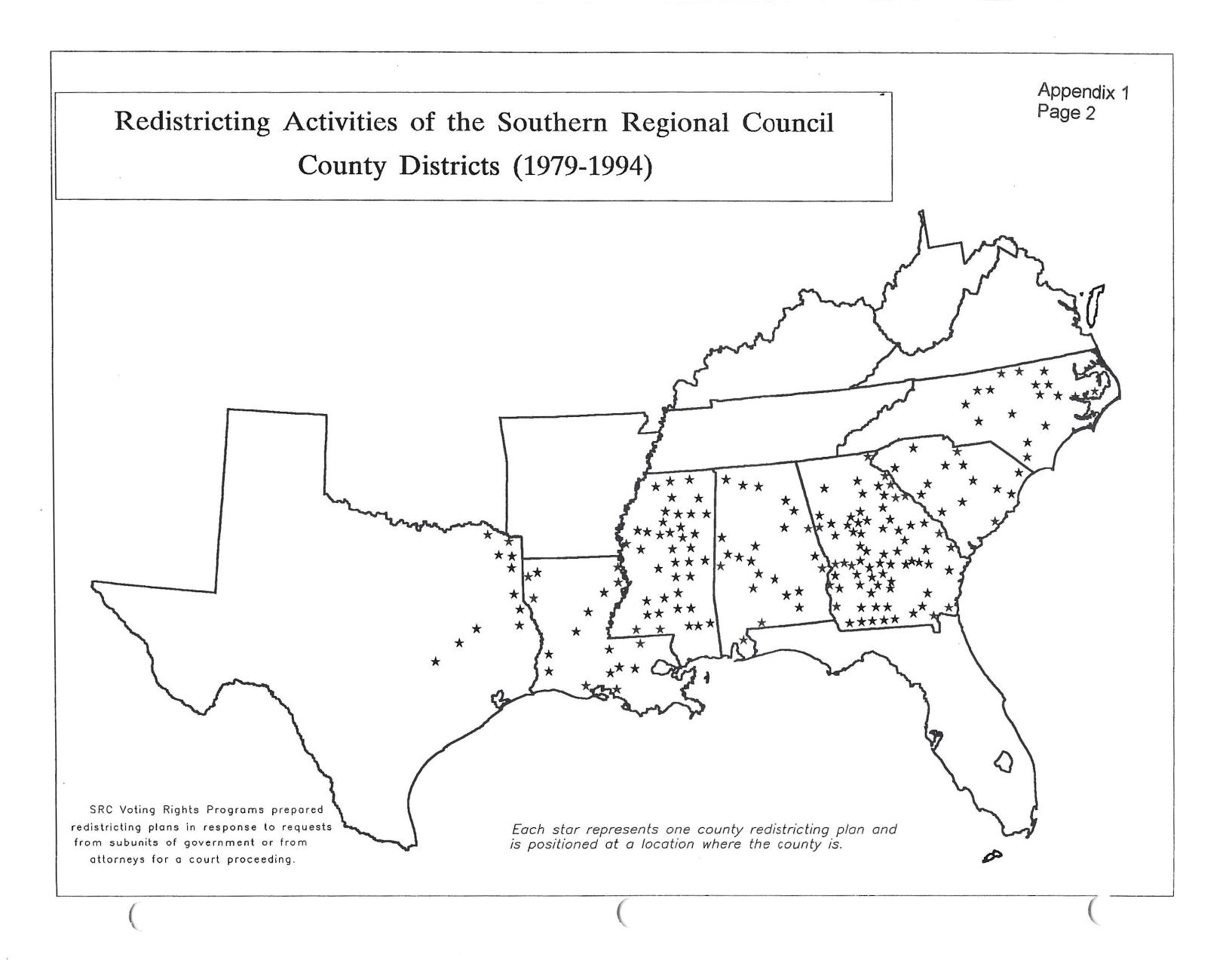

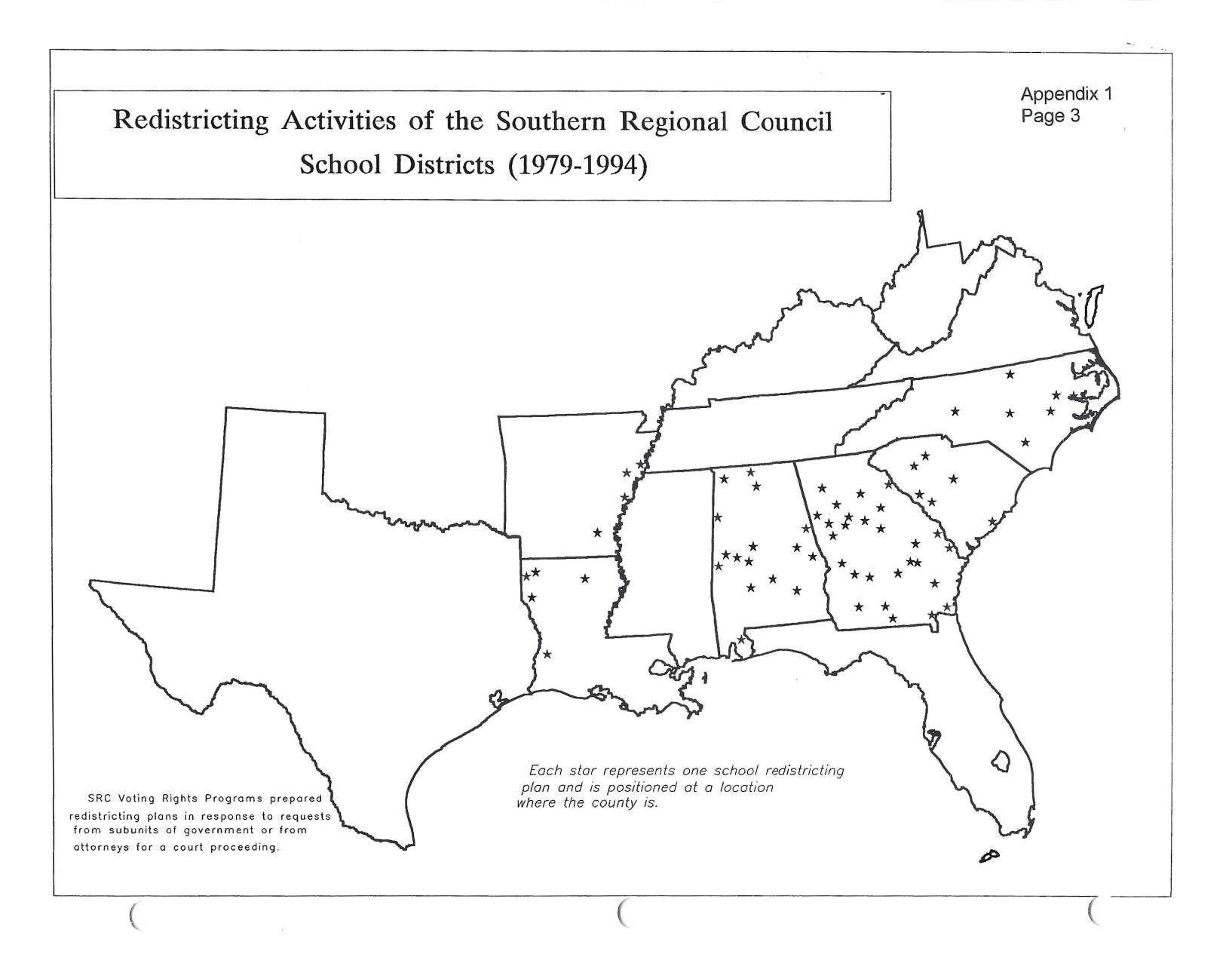

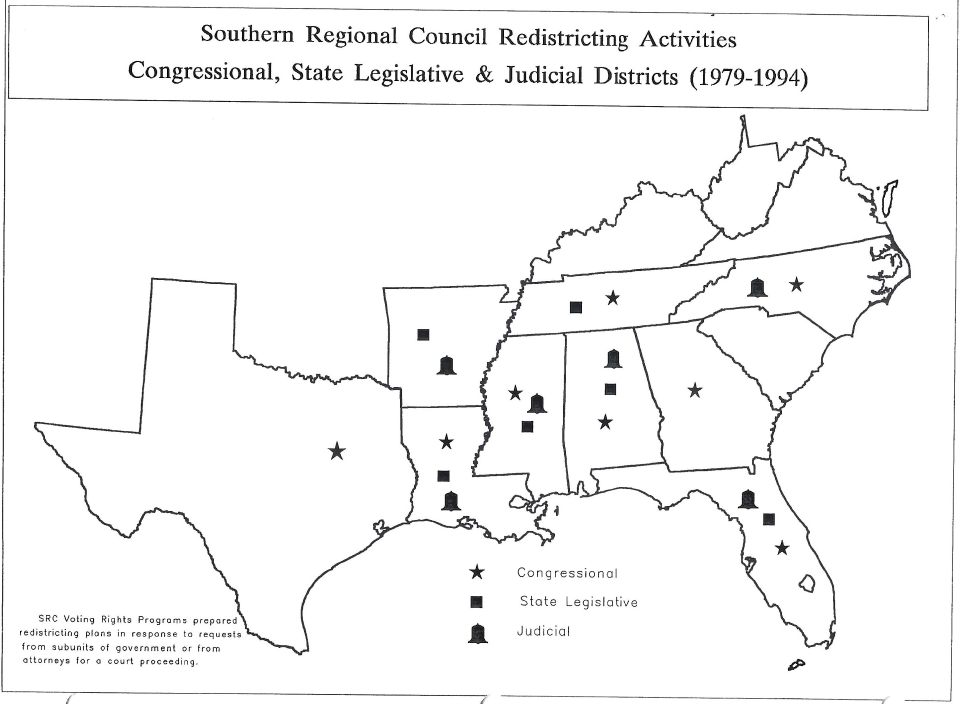

- Redistricting Infrastructure: The Council designed plans in over 300 jurisdictions — including congressional, state legislative, city councils, counties, school boards, and judicial systems — enabling hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Black voters to elect candidates of their choice.

- Training and Technical Support: SRC trained the first generation of Black, Latino, and Asian American redistricting experts, embedding democratic planning standards in local governance.

- Legislative Advocacy: The Council helped renew the Voting Rights Act in 1982 (despite opposition from President Ronald Reagan) and pass the National Voter Registration Act in 1993, working with coalitions to protect and expand access.

- Strategic Framing: SRC reframed democracy as a structural commitment — not just a moral ideal — and built the technical tools to make it real.

- Legislative Black Caucuses: The Council helped establish legislative Black caucuses in four Southern states, strengthening institutional representation and policy coordination.

Building Black Political Power – Visual Evidence: SRC’s Redistricting Impact (1979–1994)

💼Economic Democracy

- Launched the Worker Climate Report to rank states by support for workers and families

- Advocated for federal programs to revitalize neighborhoods under Reagan and Bush

- Challenged exclusionary economic policies with data and grassroots organizing

📚 SRC and Education Reform

- Partnered with Bob Moses to bring the Algebra Project to seven Southern states

- Supported dropout turnaround programs and equitable school funding

- Linked math literacy to citizenship and democratic participation

📻Media & Civic Memory

- Published Southern Changes magazine

- Published Voting Rights Review

- Produced the Peabody-winning radio series Will the Circle Be Unbroken

- Documented local civil rights leaders and movement history for national audiences

📎 Browse Southern Changes archives

Appendices — Maps and News Coverage

Full Paper

Growing Democracy in the South, 1977–1994

By Steve Suitts Presented at the University of Florida, Gainesville – October 25, 2003

SRC and the Civil Rights Movement History

In his thoughtful, caring paper, Triangles of Change, written for this conference about SRC in the Civil Rights Movement, Jeff Norrell concludes with the same observation that he used to end an earlier paper delivered at SRC’s 50th anniversary. He states:

“One Council veteran who can remember the days when the Council’s view on the South was cited by the New York Times with almost Biblical authority, and the times when the executive director jumped on an airplane to Washington to tell John Kennedy what a civil rights bill ought to look like, observed that since the mid-1970s Council activities sometimes seemed like drops of water on a vast desert.”

Jeff Norrell makes it plain that he does not entirely share this perspective, but also he does not directly confront its assumptions or its facts. This afternoon, I intend to challenge both — abandoning a long-held position, which has been to leave it to St. Peter, not New York editors or Southern historians, to make a final accounting of my contribution to the people and land I love.

Bluntly put, anyone who believes that a quote in the New York Times and a day visit with a U.S. President are the most effective ways to root and grow democracy in the American South is an elitist — or a former New York Times reporter…

Actually, looking back on my days at SRC, I am surprised how often over the years I was quoted in the Times, and in fact I did go to the White House a few times. Both have their role to play, but only an elitist, ineffective view of democratic change would place those institutions at the center of enduring strategies for realizing fundamental, democratic improvements in the South — especially in the 1970s and 1980s.

The South I have known has never had rich soil for growing democracy, but I have never considered it a “desert” — a term evoking the same antidemocratic imagery as did H.L. Mencken when he condemned the South in 1917 as “almost as sterile artistically, intellectually, and culturally as the Sahara desert.” It may have been at that time an accurate appraisal of the white South’s ruling class, but it was certainly wrong about the people of the South — as wrong as the image of SRC as “drops of water” and of the South as the “desert” after the mid-70s.

The Political Context

Two moderate Southern Presidents provided the bookends for my term as SRC director, but Ronald Reagan’s presidency provided the real context. I arrived at SRC for my first day of work on July 11, 1977. Julius Chambers was SRC’s president. Our old friend, Raymond Wheeler, was its past president. Jimmy Carter, a former SRC advisory committee member, was the U.S. President. Ray Marshall, an SRC member, was U.S. Secretary of Labor. Hodding Carter and Patt Derian, recent members of the SRC Executive Committee, were high-ranking officials of the State Department. Several other former staff members and SRC members were in the Carter Administration. There also were other remarkably talented people of goodwill in the Carter Administration, including Drew Days, who was the Assistant U.S. Attorney General for Civil Rights after having served for 8 years at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Under the circumstances, I didn’t have to fly to Washington to tell a President or his administration about what a good civil rights bill would look like. They already knew. My first responsibility was to save SRC from financial and spiritual ruin — and to lead SRC in strategies that would implant democratic principles as the everyday governing terms of state ways and folkways across the South.

Later, in the ’80s, after the election of Ronald Reagan and George Bush, SRC did go to Washington — not to advise the Presidents — but to work with national coalitions to keep those Presidents and their party from destroying the laws that Lyndon Johnson — not John Kennedy — had signed.

After 12 years of Republican rule in the White House, I ended my tenure at SRC with Bill Clinton as President, with former SRC staff member Vernon Jordan as his chief informal advisor, and several SRC members, including Lottie Shackelford, serving in President Clinton’s White House or as his political advisors.

Throughout my years at SRC, I assumed that the White House and the media were very important for creating Southern changes, but I also assumed that it was even more important to enable the historically disfranchised to use their democratic rights to the fullest — in order to control and influence the major institutions that could improve their lives and to help elect the Presidents, Congresses, and other public officials that would respond faithfully to meet their needs.

On These Terms, What Did SRC Accomplish?

On these terms, during my tenure, what did SRC accomplish for the good of the South and the nation? Here is my own summary accounting of what my colleagues and I were able to achieve:

In the Field of Political Democracy

- SRC helped more than 500 local African American community leaders challenge unfair voting schemes that denied the local Black community the opportunity to elect the candidates of their choice.

- SRC was the first organization in the nation to develop and train community leaders in using computer software to develop fair redistricting plans.

- SRC drew fair redistricting plans for at least 95 city councils, 125 county governments, 55 local school boards, congressional districts in 8 Southern states, redistricting plans for the state legislatures in 6 states, and plans for the statewide judicial systems in 6 Southern states. 1

- This work enabled African American voters to make their votes count — by creating election districts where literally thousands of new Black and white officials were beholden to Black voters for public office — often for the first time.

- From 1977 to 1994, the number of Black elected officials almost doubled in the South and tripled in the Deep South. 2

- SRC played a vital role in assuring that in 1982 the U.S. Congress renewed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 for 25 years — despite the opposition of President Ronald Reagan.

- SRC assisted in organizing or incorporating legislative Black caucuses in 4 Southern states and provided research and technical assistance on legislative issues to both Black and white legislators representing low-income districts.

- SRC trained and developed America’s first generation of African American, Latino, and Asian American experts in redistricting — more than 35 young activists and scholars who continue this work nationally.

- An SRC report prompted the adoption of the first national affirmative action plan for the entire U.S. court system, and another led to the U.S. Judicial Conference banning federal judges’ membership in segregated social clubs.

- SRC was instrumental in assuring the enactment of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, which has added millions of low-income voters to registration rolls across the South and nation.

- SRC staff met at the White House about this issue and was one of 15 organizations invited by the President to recognize its role in achieving passage of the Act.

In Economic Democracy

- SRC established the nation’s first Worker Climate Report to counterbalance the popular “business climate reports” of that day. For the first time, a data-driven report measured not how well the 50 states were as places for corporations to do business, but how the states were ranked as places for workers and their families to have a good, decent life.

- This report helped to re-focus how the nation measures economic growth and economic benefits.

- SRC issued the first comprehensive study of “day labor pools” in the South and nation. This report looked at the abuses of a system that depends on the vulnerability of the homeless and the down-and-out for profit and remains today, according to activists and scholars in the field, the most comprehensive work.

- SRC helped rally Southern organizations to save the Federation of Southern Cooperatives from being closed through politically inspired federal investigations.

- SRC challenged the South’s electric utility cooperatives — the rural South’s largest employer and the South’s largest democratic economic institutions. While SRC failed to make these institutions truly democratic and responsive to their low-income members, its challenges prompted reforms that improved employment and services in several parts of the South.

In Education — The Cornerstone of Democracy for the South

- SRC brought to the South Bob Moses’ Algebra Project, which continues to work in some of the poorest schools in seven Southern states to ensure that all students achieve and to open up the tools of citizenship in the 21st century. 5

- SRC worked with 15 urban school districts to address the alarmingly high rates of push-out and dropout of poor and African American students and to increase student achievement in the middle grades where achievement gaps widen. In all schools and districts, some real changes took place for the better.

- SRC supported the work of 20 community leaders and a dozen community groups in seven Southern states to develop the skills and experience to become as effective in helping or pressuring schools to educate the neediest students as community leaders once were in pushing desegregation.

- SRC established the Delta Principal’s Institute to improve the poorest schools in the Mississippi River Delta. Some of this work continues through the state department of education.

In the Democratic Marketplace of Ideas

- SRC helped to keep alive the power of memory, democratic ideals, and progressive ideas.

- SRC re-established its regional journal, Southern Changes, which published vital stories and commentaries found nowhere else — and has done so for the last 25 years through the leadership of Allen Tullos.

- SRC built the Lillian Smith Book Awards into the oldest, most prestigious regional book award in the South, recognizing and celebrating great works too few others honored.

- SRC published a host of newsletters that kept activists connected to one another and to the region’s issues.

- SRC’s reports on the South’s enlarging poverty during the Reagan years were among the first to document how the federal government had transformed the “War on Poverty” into a “war on the poor.”

- In 1984, SRC sponsored the Southern Network, a cable programming network reaching over 1 million households in the three states of the nation’s first “Super Tuesday” presidential primary. At a time when candidates were given an average of 12 seconds of on-the-air time for their own words, the Southern Network was the first to regularly telecast gavel-to-gavel — the full speeches of presidential candidates over the four months of the primary campaign. SRC established a practice that another upstart at that time, C-SPAN, quickly adopted and has followed in every presidential election since.

- SRC developed and funded over 16 years an ambitious radio series, broadcast nationally for the first time in 1997 (after my term). The Peabody Award judges in 1998 described Will the Circle Be Unbroken as “brilliant,” and in my judgment it is the best radio program ever produced in America on the civil rights movement because of the technical qualities that producer George King achieved and because the programs lifted up the voices and wisdom of the movement’s local leaders who were the heart, soul, and true heroes of that great democratic moment in American life. The program has been rebroadcast nationally twice and is now used as a teaching aid in some Southern schools.

Closing Reflection

This summary accounting leaves out many of the institutional and personal changes that I think were important in assessing SRC’s impact on the South and nation during my watch. Yet, on its own factual basis — even allowing for a favorable interpretation of the facts I may have added here and there — I believe this list of SRC work represents far more importance and impact than “drops of water on a vast desert.”

Through the efforts of a small, remarkably dedicated and talented group of men and women of goodwill who were my colleagues on the SRC staff and as SRC members, this collective work helped to bring all of us, in our own lifetime, closer to the goal that George Mitchell first described as an “equal and democratic South.”

It also should help all of us understand better how democracy can grow throughout our region and nation. The simple lesson of my years at SRC reiterates what every dirt-poor Southern farmer over many generations has known about growing black-eyed peas. Yes, growing democracy in the South is for me like growing black-eyed peas, that staple of the historical South’s diet — virtually non-fat and high in carbohydrates necessary for endurance — the food that the South — regardless of race or color — has celebrated for centuries each New Year’s Day as a promise of prosperity and good fortune.

The truth about growing black-eyed peas is the truth about growing democracy in the South. Simply put, the best crops rarely grow in the richest soil.

Footnotes

1 Most of the information for this summary accounting comes from the annual reports and other publications of the Southern Regional Council from 1977 until 1995 and from occasional news articles in the New York Times

2 “Number of Black Elected Officials in the United States, As of July, 1977,” Joint Center for Political Studies, 1978; “Number of Black Elected Officials in the United States, by State and Office, January 1995” Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, 1995.

3 See http://vvvvw.fec.gov/pagesinvrareport2000/nvrareport2000.htm.

4Maurice Emsellem and Catherine Ruckelshaus, “Organizing for Workplace Equity: Model State Legislation for `Non-Standard’ Workers, National Employment Law Project, November, 2000 ” p. 22, fn. 15, accessible at http://vvvvw.nelp.org/docUploads/pub17%2Epdf; “Statement By The National Employment Law Project, Inc. Submitted To The Commission On The Future OF Worker-Management Relations,” Washington, DC, June 2 1994, p.3, fn.2.

5 Robert P. Moses and Charles E. Cobb, Jr., Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights (Beacon Press: Boston), 136.

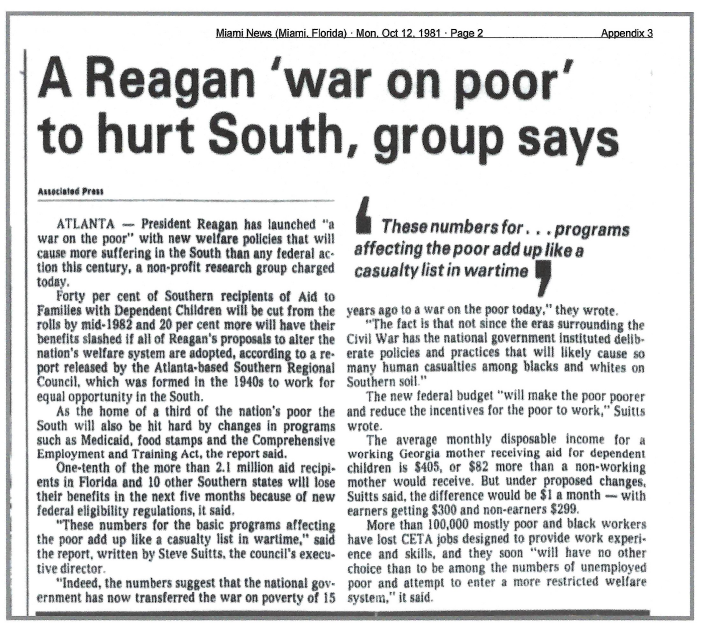

Appendix 2: New York Times Coverage of Reagan’s Voting Rights Position

“Voting Rights Backers Assail Reagan’s Stand” By Reginald Stuart, The New York Times, November 8, 1981

Dozens of organizations that support extension of the Voting Rights Act said today that changes proposed by President Reagan would threaten the rights of millions of minority voters…

“His proposals to change the House bill on these two points would bring back endless delays and subtle harassment and would jeopardize the newly won voting rights of millions of Black and Hispanic voters throughout the nation,” the statement added.

“The President’s position will ‘support’ an effective voting rights act to death if his views prevail in the United States Senate,” said Steven Suitts, executive director of the Southern Regional Council.

Read full article (archival access)

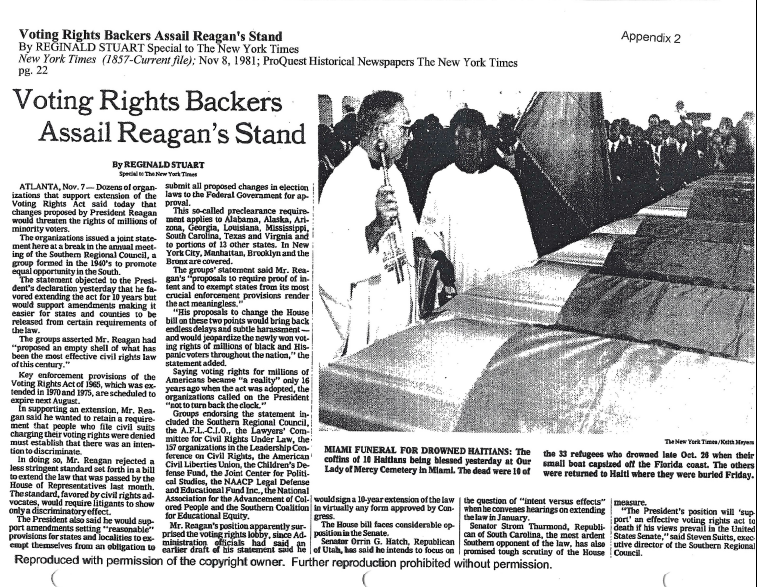

Appendix 3: Miami News Coverage of Reagan’s “War on the Poor”

“A Reagan ‘War on Poor’ to Hurt South, Group Says” Miami News, October 12, 1981

President Reagan has launched “a war on the poor” with new welfare policies that will cause more suffering in the South than any federal action in this century, a nonprofit research group charged Monday…

“These numbers for the basic programs affecting the poor add up like a casualty list in wartime,” said the report, written by Steve Suitts, the council’s executive director.

“Indeed, the numbers suggest that the national government has now transferred the war on poverty of 15 years ago to a war on the poor today.”

Miami News Coverage of Poverty Program Cuts (1981)

New York Times: Voting Rights Backers Assail Reagan’s Stand (1981)

This article was written by Steve Suitts with an editorial framing by BP Editorial and is published here with permission as part of our Southern Civic Memory series.