Outside The East 10 Claver Place Brooklyn

The East – Institutional Overview

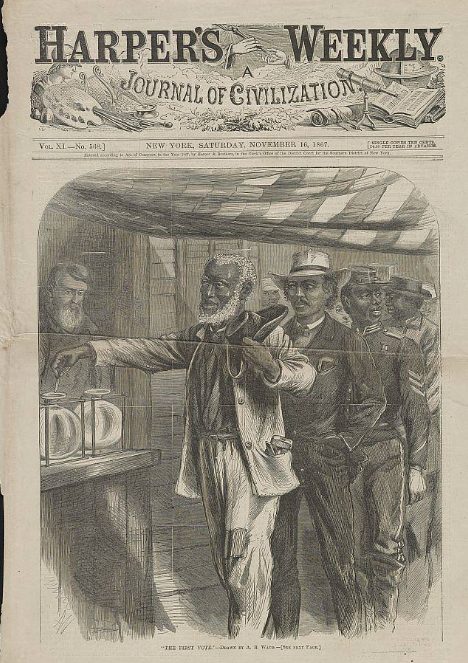

The East (1969–1986) was more than a cultural nationalist institution — it was a sovereign Black ecosystem built in the heart of Brooklyn, New York. It was located at 10 Claver Place in the historic Bedford Stuyvesant Section of Brooklyn, New York. Founded in 1969, it fused education, economics, and art into a living blueprint for self-determination. This post traces its rise, key personalities, and enduring legacy, with side projects on its most vital institutions.

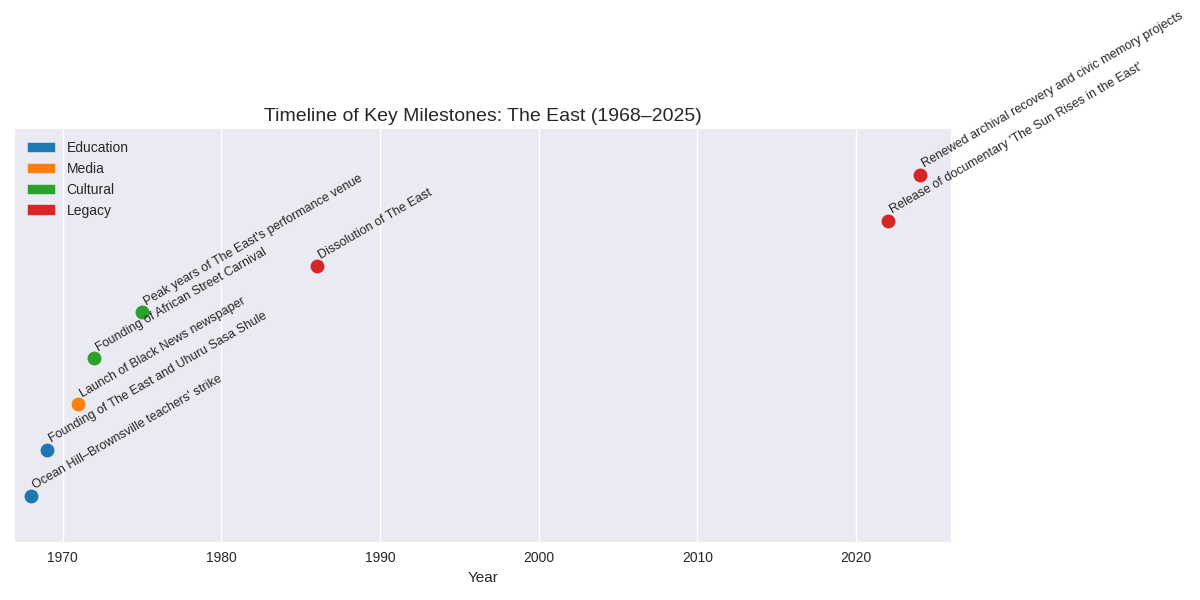

📊 Timeline: The East’s Institutional Arc (1968–Present)

| Year/Period | Milestone/Event | Category | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Ocean Hill–Brownsville teachers’ strike catalyzes demand for Black school control | Education | Sets the stage for Uhuru Sasa Shule’s founding |

| 1969 | Founding of The East and Uhuru Sasa Shule at 10 Claver Place | Institutional Birth | Core ecosystem established |

| Early 1970s | Launch of Black News newspaper | Media | Editorial arm of The East; national circulation |

| Early 1970s | Founding of African Street Carnival by Segun Shabaka | Cultural Event | Evolves into International African Arts Festival |

| Mid 1970s | Peak years of The East’s performance venue | Cultural Venue | Hosted Sun Ra, Max Roach, Gil Scott-Heron, and others |

| 1980s | Uhuru Sasa Shule moves into the Armory at 357 Sumner Ave | Education | Also hosts NBIPP organizing meetings |

| 1986 | Dissolution of The East | Institutional Shift | Financial and ideological pressures |

| 1999 | Kalonji Lasana Niamke’s Cornell thesis on The East’s institutional model | Legacy Scholarship | Academic recovery begins |

| 2022 | Release of The Sun Rises in the East documentary | Media Legacy | Directed by Tayo and Cynthia Gordy Giwa |

| 2023–2025 | Renewed archival recovery and civic memory projects | Legacy Activation | Timeline, quizzes, explainer blocks, and oral histories underway |

Why This History Matters

This post is part of our broader effort to document the movements, organizations, and leaders that emerged from the 1970s through the late 1990s — a period often overlooked, yet foundational to Black civic infrastructure. The institution profiled here exemplifies Black cultural nationalism: it built independent schools, media platforms, and cooperative spaces rooted in African heritage and political consciousness. While some of its members maintained ties to revolutionary networks, its core mission prioritized cultural sovereignty and community control. That ideological stance places it squarely within our Northern separatist/self-defense current — a lineage defined by grassroots governance, educational autonomy, and resistance to state dependency. By recovering its full arc, we honor a blueprint of self-determined Black leadership that shaped the civic terrain of Brooklyn, the Northest, and beyond.

🔥 Origins and Ideological Roots

The East was founded by Jitu Weusi (Les Campbell) and members of the African American Student Association in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Inspired by the Congress of African People and the Black Power movement, it embraced cultural nationalism, emphasizing:

- Pan-African consciousness

- Independent Black institutions

- Community control of education and economics

For New York City and vicinity, the institution quickly became a hub for political education, cultural programming, and economic self-sufficiency.

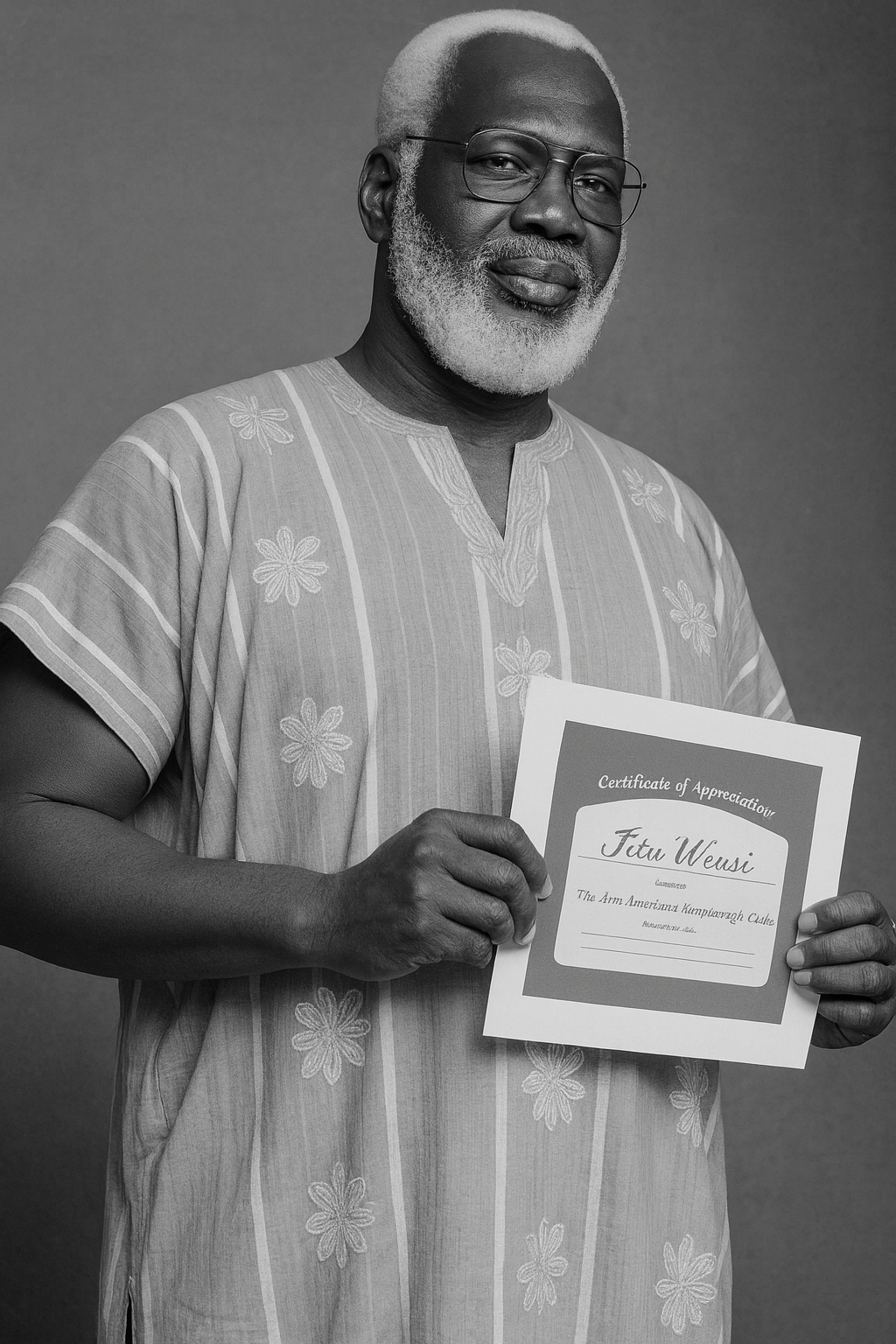

Jitu Weusi: Architect of Sovereignty and Institutional Builder

Jitu Weusi (born Leslie R. Campbell) was the principal founder and a towering figure — both literally and ideologically — in Black educational and cultural nationalism. Standing about 6 feet 9 inches tall, Weusi’s physical presence matched the scale of his ambition: to build a sovereign Black ecosystem rooted in Pan-Africanism, cooperative economics, and cultural pride. A Brooklyn native and public school teacher, Weusi rose to prominence during the 1968 Ocean Hill–Brownsville teachers’ strike, where he championed community control of schools and exposed the limits of liberal integrationist politics.

In 1969, Weusi co-founded The East and Uhuru Sasa Shule alongside Aminisha Black and other members of the African American Student Association. His vision was uncompromising: to build a sovereign Black ecosystem rooted in Pan-African ideology, cooperative economics, and cultural pride. Under his leadership, The combined institution housed a school, newspaper (Black News), bookstore, food co-op, performance venue, and publishing arm — all designed to nurture Black consciousness and self-determination.

Weusi was also a cofounder of New York Metropolitan Black United Front and the National Black United Front, the International African Arts Festival, the African-American Teachers Association, and African Americans United for David Dinkins, extending his influence far beyond Brooklyn. His legacy lives on in the institutions he built and the generations he mentored — including many who continue the work of cultural sovereignty today.

Contextual Explainer: Why The East Emerged When It Did

1968–1969: From Crisis to Creation

In the wake of the 1968 Ocean Hill–Brownsville teachers’ strike, many Black educators and parents in Brooklyn lost faith in the promise of integration. The strike, sparked by demands for community control of schools, exposed deep racial divides within New York’s liberal establishment. For Jitu and his comrades, the lesson was clear: Black educational sovereignty could not be negotiated — it had to be built.

The organization was not born in isolation — it was part of a national wave of Black nationalist institution-building. From Newark’s Spirit House to Detroit’s Shrine of the Black Madonna, cultural nationalists were creating schools, newspapers, bookstores, and food co-ops that reflected their values. What made The East unique was its scale and coherence: a single building in Bed-Stuy housed a school, a newspaper, a performance venue, a food coop, and a political vision. It was a blueprint for liberation — and a challenge to the city’s power structure. This broader wave of Black nationalism swept urban centers in the late 1960s. In the aftermath of Malcolm X’s assassination and amid growing disillusionment with integrationist politics, cultural nationalists sought to build independent institutions that could nurture Black consciousness, economic autonomy, and political agency and reinforce a shared vision of liberation.

Its ideological stance was unapologetically Pan-African and anti-imperialist, yet deeply rooted in local community needs. Members didn’t just theorize sovereignty — they practiced it daily, through cooperative economics, youth education, and cultural production. The institution’s refusal to compromise with city bureaucracy or dilute its message made it both revered and marginalized. Yet its influence rippled far beyond Brooklyn, inspiring similar efforts in Newark, Detroit, and Atlanta, and laying the groundwork for future Afrocentric schools, festivals, and media platforms.

✊🏾 Aminisha Black: Founding Educator and Institutional Architect

Aminisha Black was a cofounder of both The East and Uhuru Sasa Shule, playing a pivotal role in shaping their educational and ideological foundations. As an early member of the African American Student Association, she worked alongside Jitu and Adeyeme Bandele to build a school that centered African heritage, political consciousness, and cultural pride. Her leadership extended beyond curriculum — she mentored generations of students and educators, helping institutionalize the ethos of Black self-determination.

Black’s contributions were especially vital in the early years of Uhuru Sasa, where she helped craft a pedagogical model rooted in liberation, not assimilation. Her work ensured that The East’s educational wing was not just radical in theory, but rigorous in practice.

🧠 Key Personalities and Builders

| Name | Role | Legacy |

|---|---|---|

| Jitu Weusi | Founder, educator, strategist | Architect of Uhuru Sasa Shule; led ideological and institutional development |

| Adeyeme Bandele | Organizer, educator | Helped shape curriculum and political forums |

| Basir Mchawi | Media and education leader | Anchored Black News and adult education efforts |

| Segun Shabaka | Cultural programmer, festival director | Directed the African Street Carnival; sustained Pan-African cultural diplomacy |

| Yusef Iman | Poet, playwright, cultural educator | Renamed by Malcolm X; infused The East’s programming with revolutionary poetics and led youth workshops rooted in Black Arts pedagogy |

| Aminisha Black | Cofounder, educator, youth advocate | Cofounded The East and Uhuru Sasa Shule; advanced African-centered pedagogy and mentored generations in cultural pride and political awareness |

These leaders blended pedagogy, performance, and politics — building institutions that taught liberation as a lived experience.

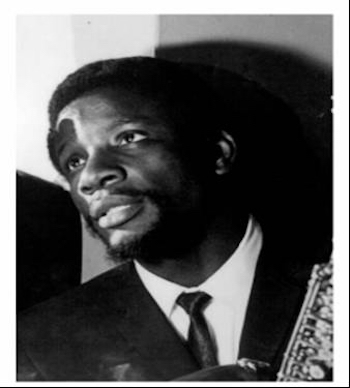

Among the cultural architects was Yusef Iman, a poet, playwright, and educator whose work helped shape the institution’s artistic and ideological voice. A founding member of The Last Poets and longtime Brooklyn resident, Iman brought a fierce commitment to Black consciousness and creative expression, anchoring The East’s performance programming and youth workshops in revolutionary poetics. I recall Yusef to be among the most humble of human beings I have ever encountered.

Yusef Iman was a foundational cultural figure whose artistic and ideological journey intersected directly with Malcolm X. Born Joseph Washington Jr. in Savannah, Georgia, he became deeply involved in the Black liberation movement through both theater and political organizing. His transformation into Yusef Iman was not just symbolic — it was bestowed by Malcolm X himself.

Relationship with Malcolm X

In the early 1960s, Iman joined Muslim Mosque Inc. and the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) — both founded by Malcolm X after his departure from the Nation of Islam. Malcolm, impressed by Iman’s unwavering commitment, renamed him “Yusef Iman” — Yusef being the Arabic form of Joseph, and Iman meaning “faith.” This renaming was a spiritual and political affirmation, marking Iman as a trusted disciple in Malcolm’s post-NOI vision.

Revolutionary Theater and Cultural Work

Iman’s artistic career flourished alongside his activism. He gained theatrical experience at Amiri Baraka’s Spirit House in Newark and Roger Furman’s New Heritage Repertory Theatre in New York. He performed in seminal Black Arts Movement plays like Dutchman, Black Mass, and Arm Yourself or Harm Yourself, often blending poetry, politics, and performance into a single revolutionary act.

At 10 Claver Place, Iman anchored youth workshops and curated performance programming that reflected this lineage — infusing the institution with revolutionary poetics and ideological clarity. His presence bridged the militant legacy of Malcolm X with the cultural nationalism of the Brooklyn based institution.

Basir Mchawi: Media Strategist and Educational Organizer

Basir Mchawi was a central figure in The East’s intellectual and media infrastructure. A former public school teacher and lifelong educator, Mchawi helped shape the Uhuru Sasa curriculum and later became editor of Black News, the biweekly newspaper. His work bridged pedagogy and journalism, ensuring that the message reached classrooms and communities across the country.

Mchawi’s editorial leadership gave Black News its clarity and reach — covering Pan-African politics, cultural programming, and grassroots education with rigor and urgency. After The East’s dissolution, he continued his work in adult education and media, hosting radio programs and advocating for Black educational sovereignty well into the 2000s.

🧠 Adeyeme Bandele: Curriculum Builder and Political Educator

Adeyeme Bandele was a founding member of The East and a key architect of Uhuru Sasa Shule’s curriculum. A committed cultural nationalist, Bandele helped translate Pan-African ideology into classroom practice — designing lesson plans, training teachers, and mentoring youth in political consciousness and cultural pride.

His work extended beyond pedagogy: Bandele was instrumental in organizing political forums and community dialogues that linked local struggles in Brooklyn to global liberation movements. He embodied the institution’s ethos of education as a revolutionary act, and his influence shaped generations of students and educators.

Segun Shabaka: Cultural Diplomat and Festival Architect

Segun Shabaka was the lead cultural programmer and the founding director of the African Street Carnival, which evolved into the International African Arts Festival. A master organizer and Pan-African strategist, Shabaka curated performances, vendor networks, and public rituals that turned The East’s ideology into lived experience.

Under his leadership, the festival became a cornerstone of Brooklyn’s cultural calendar — showcasing African dance, music, fashion, and food while sustaining a Black-owned economic ecosystem. Shabaka’s work exemplified The East’s commitment to cultural sovereignty and remains active today through his continued stewardship of the festival.

🏫 Institutional Infrastructure

The East operated a constellation of self-sustaining institutions:

- Uhuru Sasa Shule (“Freedom Now School”): African-centered K–12 school with a liberation pledge and culturally grounded curriculum

- Black News: Biweekly national magazine covering Pan-African politics, education, and arts

- Bookstore, restaurant, food co-op, catering service: Economic arms of self-determination

- Adult education classes: Political theory, African history, and community organizing

- Performance venue: Hosted legends like Sun Ra, Pharoah Sanders, Max Roach, and Gil Scott-Heron

🎭 Cultural Legacy: The African Street Carnival

Founded by Segun Shabaka and others, the African Street Carnival evolved into the International African Arts Festival, now a 50+ year tradition. African American residents from all across New York City and neighboring states flocked to the African Street Carnival every July 4th weekend. It was a must stop for everyone, from youth to elders, myself included. Parents brought their children; youngsters brought their parents and grandparents; boyfriends brought their girlfriends, and vice versa. It was the place you wanted to be. The African Street Carnival showcased:

- African dance, music, and fashion

- Black-owned vendors and artisans

- Pan-African solidarity across generations

Despite recent displacement from Commodore Barry Park, the festival remains a living legacy of The East’s cultural vision.

Decline and Endurance

The East dissolved in 1986 amid financial pressures and ideological shifts. Yet its legacy lives on through:

- Documentary: The Sun Rises in the East (2022), directed by Tayo and Cynthia Gordy Giwa

- Thesis: Kalonji Lasana Niamke’s 1999 Cornell study on The East’s institutional model

- Book: A View from the East by Kwasi Konadu, chronicling its educational philosophy

Why It Matters Today

The East modeled Black institutional sovereignty — a civic memory framework that resonates with:

- Community control of schools

- Black-owned media and economic cooperatives

- Cultural preservation as political education

Its blueprint remains relevant for organizers, educators, and archivists reclaiming Black civic infrastructure.

✍🏾 Personal Reflection

Growing up as an activist in Brooklyn, I had the privilege of knowing all the founders and central figures of The East. I visited 10 Claver Place often — not just as a cultural hub, but as a cooperative grocery store that nourished the community in every sense. There was no better place to absorb African culture than attending a performance at The East or making my annual pilgrimage to the African Street Carnival, a tradition that began in my teenage years.

When Uhuru Sasa Shule moved into the Armory at 357 Sumner Avenue — now Marcus Garvey Boulevard — it became more than a school. It was a gathering place for mass meetings and community organizing. Several of the New York City planning sessions for the National Black Independent Political Party, in which I proudly participated, were held there. The East wasn’t just an institution I studied — it was one I lived.

— Selwyn, Editor-in-Chief

November 8, 2025