Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC Rally at House of the Lord Pentecostal Church Brooklyn New York - On Stage Rosa Parks, to her right facing Crowd, Assemblyman Roger Green, to his Right, Countdown 88 Director, Selwyn Carter, to his Left, Dennis Rivera, President (SEIU) 1199, and to his left facing crowd and behind Rosa parks, Stanley Hill, Executive Director AFSCME DC 37. On the left of the stage in black suit and bald headed is Bill Banks, to his right is Assemblyman Frank Barbaro

Countdown 88/89: Infrastructure, Strategy, and the Rise of Black Electoral Power in New York City

Countdown 88 voter registration NYC was the most ambitious high-visibility, citywide nonpartisan voter registration and Get Out the Vote (GOTV) campaign for the 1988 presidential election in New York City. It was backed by the Community Service Society of New York (CSS),11 led by David R. Jones.

Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC Lead-up

In 1987, Bill Lynch18 approached Selwyn Carter and said, “I’ve got a campaign for you.” Prior to that point, Carter did not have much of a public identity in electoral politics, but he had been a well-known and effective New York City activist who had understudied Bill Banks in some election campaigns. Lynch and Carter had cemented a working relationship some seven years earlier when they both served on the steering committee of the Coalition to Save Sydenham Hospital.23 They had been brought together by Diane Lacey and a wide cross-section of Harlem activists, religious and civic leaders in an effort to save a West Harlem hospital targeted for elimination by Mayor Ed Koch.

Sydenham was the only hospital serving the west side of Harlem, and it sat just down the hill from City College of New York (CCNY) — Carter’s alma mater — where he had been a long-standing and popular student activist. He served as student government vice president and editor of the school’s African American newspaper, The Paper. Those roles gave him a large following on campus and deep roots in the Harlem community, stemming from his work to help community leaders make the college more accessible to students and partners from Harlem.

Selwyn Carter 29brought these relationships to bear on the Sydenham struggle and helped lead a major mobilization of thousands who fought cityhall to a standstill. He helped lead a takeover of the hospital and solidify community and worker resistance to NYC budget cuts. He organized demonstrations and picket lines to build support for workers’ demands and helped broaden support from one local community into a city-wide campaign.

Lynch knew Carter to be an effective mass mobilizer and community strategist/tactician who had built solid relationships with organized labor — in particular AFSCME Local 420 and the New York CBTU (Coalition of Black Trade Unionists) led by Jim Bell14 — along with a plethora of grassroots organizations. Carter had also been an active and founding member of the NYC Metropolitan Black United Front (BUF) led by Jitu Weusi and Herb Daughtry. BUF had been formed in response to the police killing of respected Black businessman Arthur Miller Jr., down the block from Carter’s father’s office — also a Black businessman — on Nostrand Ave and Park Place in Brooklyn. BUF led many high-profile mobilizations in New York City in the late ’70s and early ’80s around police violence and other issues.

Mobilizing Harlem and Beyond

It was Lynch 18 who introduced Carter to David R. Jones, president and CEO of the Community Service Society of New York (CSS). Prior to CSS, Jones had served as executive director of the NYC Youth Bureau and as a special advisor to Mayor Koch on race relations, urban development, immigration reform, and education.

In the late 1980s, as Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns galvanized Black voters nationwide, a quieter revolution was unfolding in New York City — one built not on speeches, but on spreadsheets, precinct maps, and voter files. Countdown 88 voter registration NYC and its successor Countdown 89 were among the most ambitious voter mobilization efforts ever mounted by a nonpartisan civic institution. Sponsored by Community Service Society voter registration under Jones’s leadership, the initiative helped empower the city’s disenfranchised majority and laid the groundwork for a new era of Black political infrastructure — culminating in the historic election of David Dinkins first Black mayor NYC.

The Bill Lynch–guided Countdown ’88 effort—built on coordinated alliances among unions, civic institutions, and grassroots organizers, and shaped by long‑range strategic planning—became a defining model for later voter‑mobilization work in New York and influenced organizers who carried its lessons into subsequent progressive campaigns.

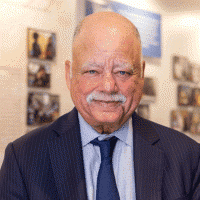

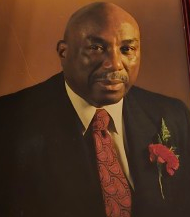

Bill Lynch (left), seen here with David Dinkins first Black mayor NYC

✊🏾 Countdown 88 NYC Campaign Kickoff: Strategic Leadership

On Sunday, December 13, 1987, a kickoff meeting was held at the headquarters of Local 1199 (now SEIU 1199), the Drug, Hospital, and Healthcare Employees Union, on West 43rd Street in Midtown Manhattan. 12 The meeting’s high-profile impact was no accident. It had been carefully staged-managed directly through Selwyn Carter Countdown 88 29director’s relationships with the two Bills of New York City politics: the well-known Bill Lynch NYC voter campaign,18 who recruited Carter and later became Deputy Mayor under Dinkins, and the quieter Bill Banks, a behind-the-scenes strategist who had served as a campaign manager and advisor to Congressman Ed Towns. These relationships were backed up by the institutional might of CSS, the Community Service Society voter registration and it’s formidable public affairs department.

Though known as a Brooklyn social service leader who had built Colony South Brooklyn Houses into a major community based powerhouse, Banks was originally from Harlem and also had a close behind-the-scenes relationship with Congressman Charlie Rangel and others in the Harlem Gang of Four. He had also been the campaign manager for a variety of NYC black elected officials, from Assemblywomen in the Bronx, to members of Congress, from Brooklyn, all members of COBED.

Bill Banks had committed to Carter29 that if he held the Countdown 88 kickoff meeting to coincide with the meeting of COBED — the Council of Black Elected Democrats — he (Banks) would deliver high-profile COBED members to the Countdown 88 voter registration NYC event in a way that would maximize public impact. This arrangement worked for both of them. For Banks, it allowed him to demonstrate to the members of COBED that he was advising that he could associate them with, and have them listed as cofounders and cosponsors of this new voter registration and mobilization campaign. (As Banks explained to Carter on more than one occasion, “elected officials get nervous when you start talking about voter registration. They get elected from a known quantity of voters. When you start talking about registering new voters, you introduce an unknow element. They don’t know how these new voters are going to vote.“) For Selwyn Carter Countdown 88 director,29 he got the power of COBED,15 representing the major black elected officials in New York City behind the Countdon 88 voter registration NYC campaign.

New York political strategist Basil Smikle Jr.20 wrote about COBED in his October 2025 article discussing the New York City mayoral race entitled — Percy Sutton, Eric Adams and the State of Black Political Power in New York:

“He (Percy Sutton) also recognized the importance of political institutions within the Black community such as the once-powerful Council of Black Elected Democrats (COBED). Though largely forgotten today, COBED was a regular gathering of Black elected officials in New York City, an effort to set policy priorities and coordinate electoral strategy. Its decisions were not binding, but the effort at consensus gave weight to the concerns of Black New Yorkers. Many, including the other members of the Gang of Four, trusted his counsel.”

The two meetings were, in fact, separate, but overlapping. Banks delivered on his commitment. The Countdown 88 voter registration NYC meeting, filled with community activists, clergy, and labor leaders, convened in the 1199 auditorium downstairs. The COBED members — consisting of every high-profile Black elected official in New York City (including Congressmen Rangel, Towns, and Owens, and Manhattan Borough President, David Dinkins) — had been meeting privately upstairs, organized by Banks on behalf of his friend, Selwyn Carter. (This is the first time this story is being revealed publicly.)

The impact of all these Black elected officials joining the Countdown 88 voter registration NYC meeting and speaking about NYC voter mobilization 1988 of the unregistered Black and Brown population was a headline grabber. Every major print outlet in New York covered the story:

- The New York Times ran the story under the headline “Voter Registration Drive Takes Aim at Minorities” on Sunday, December 13, 1987.1 Read the article

- New York Newsday wrote:

“For a broad coalition of congressmen; community, city, and ethnic organizations; labor leaders and clergy, however, it was a fitting moment for the unveiling of Countdown 88, an ambitious registration campaign designed to sign up about 250,000 New Yorkers before the November election.” Reproduced from private hard copy archive.

Newsday archive - The Amsterdam News reported on Saturday, December 19, 1987:

“A group of high-powered politicians last Saturday announced the launching of a major voter registration project with an eye on the 1988 Presidential election.”

Amsterdam News archive

In the Amsterdam News artice, Nydia Velazquez, then the national director of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, now a member of Congress, noted that the city was home to some 400,000 unregistered Puerto Ricans, whom she called, “the sleeping giant”.

The Bill Lynch NYC voter campaign strategy18 extended beyond single elections, envisioning a multi-year infrastructure-building process that would begin with Countdown 88’s voter registration, continue through the 1988 presidential primary, and culminate in the 1989 mayoral race.

Origins of Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC Campaign

Before Countdown 88 voter registration NYC became a citywide mobilization, it began as a strategic idea within Harlem’s most influential political circle — the Harlem Gang of Four — who saw NYC voter mobilization 1988 as the key to unlocking long-denied Black political power in New York. The idea for the non partisan Countdown 88 voter registration NYC didn’t originate inside CSS. It came through Bill Lynch, the trusted strategist of the Harlem Gang of Four — Congressman Charles B. Rangel, Percy Sutton, Basil Patterson, and David Dinkins. Nevertheless, the proposal aligned perfectly with CSS’s programmatic goals. At the time, CSS was already operating three smaller, non-partisan, community-based Voter Participation Projects (VPP), so Community Service Society voter registration efforts were consistent with the organization’s established mission and history.

Bill Lynch NYC voter campaign expertise, honed through years of working with the Harlem Gang of Four, made him uniquely qualified to design a voter mobilization effort that could register hundreds of thousands while maintaining the nonpartisan credentials necessary for CSS sponsorship.

By 1987, New York City had never elected a Black mayor, despite decades of promises and demographic shifts. The Gang of Four understood that real power required infrastructure — not just charisma or coalitions, but data, precinct strategy, and institutional muscle. They saw NYC voter mobilization 1988 as the key to unlocking Black political power in New York and beyond. Lynch turned to CSS, a civic institution with credibility, reach, nonpartisan standing, and a track record. Citywide Non partisan Community Service Society voter registration and mobilization represented a strategic evolution of their existing work. Under the leadership of David R. Jones, CSS stepped forward — not just as a sponsor, but as a strategic partner in reshaping the city’s political future. The timing was perfect, given the high numbers of unregistered black and brown voters in New York City and the approaching two high profile elections – presidential, and mayoral.

This wasn’t a partisan endorsement. It was a strategic investment in civic infrastructure at the right time — one that aligned with CSS’s mission to expand opportunity and engagement, to significantly expand the reach beyond the three CSS targeted, community based Voter Participation Projects (VPP).

Countdown 88 NYC Voter Registration Infrastructure and PR Campaign

The Ground War

But Countdown 88 voter registration NYC was an entirely different undertaking. It was a massive, city-wide, high visibility, non-partisan campaign with a citywide infrastructure and offices in the 4 targeted boroughs of Brooklyn, Manhattan, The Bronx, and Queens. The campaign built a citywide staff 22 and volunteer base (with the help of a key recruit by Bill Lynch – the experienced labor volunteer strategist and leader, Pat Caldwell), to register and mobilize new voters. As Vice President of Welfare Local 371 of District Council 37 (DC 37), Pat Caldwell had been one of the key leaders of the landmark 1965 New York City welfare strike. Her role was critical to the union’s organizing efforts both before and during the work stoppage.13 She was well known and well liked among New York City labor activists, allowing her to be extremely effective at volunteer recruitment. Pat had turned the Countdown 88 Manhattan main headquarters at CSS into a revolving door of union volunteers. As Countdown 88 grew, offices were established in the four target boroughs. In addition to Pat Caldwell, Anna Marta Morales served as the Citywide Latino Coordinator; Lorraine Witherspoon-Flateau (the wife of legendary political strategist John Flateau) as the Brooklyn Coordinator; Tracey Gray as the Bronx Coordinator; Norma Bradshaw as the Manhattan Coordinator; and Melvin Kelly as the Queens Coordinator. Joseph Haslip, now CSS board secretary, got his start with the organization through Countdown, serving as the Youth and Students Coordinator. After Haslip became involved in a City University of New York (CUNY) student campus takeover, John Anthony Butler took over that role.

The High Profile Media Campaign

This ‘ground war’ was supported by an equally impressive ‘air war’, implemented by the CSS Public Affairs department. Jones had convened the CSS executive staff team to strategize about how to create citywide buzz for Countdown 88. This team involved Carter, the CSS legal team, public affairs, and other department heads, and staff. It was agreed that the campaign would need to bring into New York City high profile African American civil rights personalities to promote Coundown to New York’s City’s black population. From his community activist days, Carter had been accustomed to mobilizing large gatherings using street guerilla tactics. But that wouldn’t work with CSS. Everthing had to be vetted with the lawyers to ensure it complied with the organization’s tax exempt status and that the institution was protected, especially when large crowds were involved. Carter had a flair for the dramatic, high profile civil rights names, and CSS had the budget and institutional clout to make it happen.

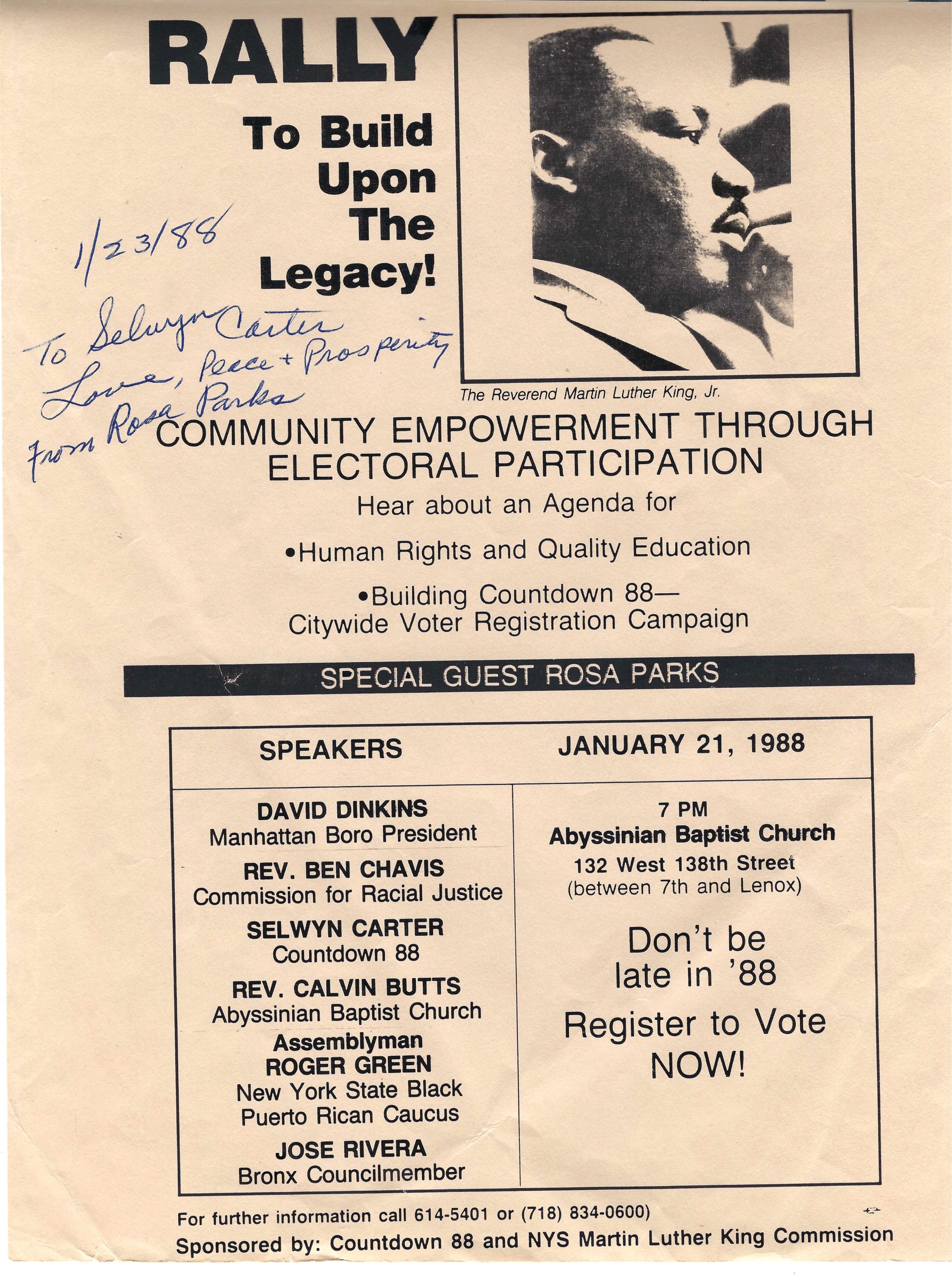

It was agreed that Rosa Parks would be the catalyst who could ignite the campaign, and, shortly thereafter, it was confirmed that we had secured a commitment from the courageous civil rights icon to associate herself with the Coundown 88 campaign. Countdown 88 brought Rosa Parks to the historic Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, to the House of the Lord Pentecostal Church in Brooklyn (headquarters of the Black United Front), and to Antioch Baptist Church in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn.25 The organization deployed resources, staff, and technical expertise to support voter registration, education, and mobilization across New York City.

The air war included more. In order for the campaign to succeed, Countdown had to reach black youth, who were high among the city’s unregistered. Countdown secured rap icons LL Kool J and RUN DMC26 to make video public servcie announcements. And Harlem Gang of Four leader, Percy Sutton,21 who owned Inner City Broadcasting, the home of the very popular WBLS and WLIB radio stations,17 gave Countdown 88 a slot on the radio every mornintg to update the public on the campaign. Every morning during “Drive Time’, as commuters were headed off to work, Carter was on WLIB radio station with updates on the campaign. These included highlights on voter registration activity and locations where the Votemobile was going to be. (Bill Banks had secured from State Senator Joseph Galiber of the Bronx a commitment to allow Countdown 88 to use his campaign bus as the Countdown 88 votemobile. This bus came equipped with a stage and massive loudspeakers and was decorated with the Countdown 88 slogan, Don’t Be Late in ’88-Register to Vote Now! (Carter had studied the voter mobilization campaign in Chicago four years earlier and was convinced that a catchy slogan ws essential for the campaign to take hold. In 1983, the “Come Alive October 5” campaign was a massive, multi-racial voter registration drive that created a groundswell prior to Harold Washinton’s election). A story entitled, Sidewalk Sale on Democracy, in New York Newsday by Dennis Duggan on Sunday Februsry 21st, 1988, had this to say about the Votemobile,3,24 “Carter..parked a 25 year old battered blue and white bus in front of the World Trade Center on Church Street all last week imploring New Yorkers to become voters.”

Countdown 88 is credited with registering hundreds of thousands of New York City unregistered voters, particularly in the black community. Those numbers were validated when historic numbers of African Americans and voters of color turned out to vote during the 1988 Presidential Primary in New York City. Countdown had teamed up with the Citizenship Education Fund16 to run a major city-wide non-partisan Get Out The Vote campaign (GOTV). It deployed vans in the 4 target boroughs and hired hundreds of youth to flush the vote out in the black neighborhoods of New York City.

Children of the Movement: Countdown 88 NYC GOTV Campaign Historic Moment

The New York primary campaign, which saw Jesse Jackson make history in New York City, had concluded in April — and Countdown 88 had continued its nonpartisan mission into the general election. Expanding outreach, deepening infrastructure, and mobilizing new voters across the city, the campaign shifted into high gear once more by late summer. It culminated in a landmark rally at Greater Bibleway Temple in Brooklyn that brought together the children of three iconic movements to launch its Get Out The Vote drive.

On Sunday, August 21, 1988, Countdown 88 convened a landmark gathering at Greater Bibleway Temple in Brooklyn to launch its Get Out The Vote (GOTV) drive. The event brought together Jonathan Jackson, Dexter King, and Attallah Shabazz — the children of Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X27 — in a powerful show of generational unity. Their presence electrified the congregation and underscored Countdown’s mission: to connect the legacy of civil rights with the urgency of voter mobilization. The symbolism was unmistakable — the heirs of three iconic movements standing together in Brooklyn, calling on Black New Yorkers to register, organize, and vote. It was one of the most resonant moments of the campaign, and a testament to Countdown’s cultural reach and strategic vision.

Countdown 88 received extensive press coverage across New York City and nationally. Articles about Countdown 88 were published in The New York Times and Newsday, December 13th, 1987; the Amsterdam News, December 18th, 1987;4 New York Newsday, January 11, 1988; The New York Times, January 21st, 1988;2 Newsday, January 22nd, 1988; The New York Times, January 24th, 1988; Newsday, January 24th, 1988; the New York Observer, January 25th, 1988;6 The City Sun, January 27th, 1988;7 USA Today, February 1st, 1988;5 Newsday, February 3rd, 1988; The New York Times, February 14th, 1988; Newsday, February 19th, 1988; Newsday, February 21st, 1988;3 Noticias Del Mundo, March 30th, 1988;10 The City Sun, August 17th, 1988; Newsday, August 17th, 1988; Newsday, August 22nd, 1988; The New York Daily News, August 22nd 1988;8 The Amsterdam News, August 27th, 1988; and The New York Voice, August 27th, 1988;9

Building Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC Infrastructure

Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC focused on the 1988 presidential cycle and was credited by press reports with registering hundreds of thousands of new black and Latino voters in New York City. Tremendously pleased by the campaign’s success, Jones decided to extend it to the 1989 mayor’s race in New York City. That decision proved to be historic because the Countdown 88 voter registration NYC campaign is credited with building the infrastructure leading directly to the election of David Dinkins first black mayor NYC.19 Countdown 89 built upon the successes of Countdown 88. The initiatives trained organizers, mapped precincts, tracked voter files, and mobilizrd hundreds of thousands, if not millions of voters. They weren’t just reactive — they were architectural.

🏛️ CSS’s Strategic Departure

For the Community Service Society, the Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC campaign marked a strategic departure. The organization had long focused on poverty, housing, and economic justice, with a much smaller voter registrtion footprint. But Countdown demonstrated that civic engagement wasn’t adjacent to those goals — it was foundational. Under David R. Jones’s leadership, CSS showed that a nonpartisan institution could play a catalytic role in electoral empowerment without compromising its broader mission. Countdown 88 marked a shift — proving that civic engagement was not just compatible with CSS’s mission, but essential to it.

David R. Jones — whose civic leadership at CSS helped expand the conditions for Black electoral engagement in New York — comes from a lineage of public service shaped by his father, the late Judge Thomas R. Jones. A leading civil rights activist and co-founder of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, Judge Jones laid the groundwork for community-based empowerment. David’s support for the nonpartisan Countdown 88 and Countdown 89 campaigns aligned CSS with a broader movement for enfranchisement and helped catalyze historic outcomes. Jesse Jackson’s 1988 New York breakthrough and the subsequent election of David Dinkins as the city’s first Black mayor must be understood within the context of the infrastructure and momentum built by Countdown 88 and Countdown 89.

How Countdown 88 Voter Registration NYC Compares to Modern Campaigns

The Countdown 88 voter registration NYC campaign pioneered methods that remain relevant to contemporary organizing, though the tools and technology have evolved dramatically. Understanding what made Countdown 88 successful—and how it differs from modern efforts—offers valuable insights for today’s organizers.

Scale and Ambition

Countdown 88’s goal of registering 250,000 voters in a single year was audacious for 1988. By comparison, modern campaigns like When We All Vote (founded 2018) and Fair Fight Action aim for millions of registrations nationwide, but they operate with digital infrastructure Selwyn Carter Countdown 8829 organizers could only imagine. What Countdown achieved with clipboards, phone banks, and the NYC Votemobile 1988, modern campaigns accomplish with online registration portals, text banking, and social media advertising.

Yet the fundamental challenge remains the same: converting civic awareness into actual registration and turnout. Countdown 88 voter registration NYC registered hundreds of thousands through intensive person-to-person contact—a labor-intensive model that proved more effective than modern click-to-register campaigns at ensuring follow-through.

Institutional Backing vs. Decentralized Networks

The Community Service Society voter registration history and backing gave Countdown 88 institutional credibility, legal protection, and financial resources that many grassroots efforts lacked. CSS’s nonprofit status allowed Countdown to accept foundation grants and maintain nonpartisan credentials while doing politically consequential work.

Modern voter registration exists in a more fragmented landscape. While organizations like Rock the Vote and HeadCount continue institutional voter registration work, much contemporary organizing happens through decentralized networks, social media mobilization, and ad-hoc coalitions. This decentralization offers flexibility but sacrifices the coordinated infrastructure that made NYC voter mobilization 1988 so effective.

Technology: From Votemobiles to Digital Tools

Countdown 88’s iconic NYC Votemobile3,24 1988—a decorated campaign bus with loudspeakers that traveled to high-traffic areas—represented cutting-edge voter outreach in 1988. Today’s equivalent might be a viral TikTok video or targeted Facebook ads reaching millions instantly.

Yet technology’s reach doesn’t guarantee depth of engagement. Countdown 88 organizers built relationships through sustained presence in communities—setting up tables outside subway stations week after week, organizing church rallies, conducting door-to-door canvassing. This created social pressure and community accountability that online registration lacks. Modern campaigns struggle to replicate the social infrastructure that made NYC voter mobilization 1988 a movement, not just a registration drive.

Political Context: Coalition vs. Polarization

Countdown 88 voter registration NYC operated in a political moment when bipartisan support for voter registration was possible. The campaign maintained nonpartisan credentials while clearly serving progressive goals—registering voters who would help elect David Dinkins first Black mayor NYC the following year.

Today’s voter registration occurs in a hyperpartisan environment where even nonpartisan registration drives are viewed through political lenses. Laws restricting voter registration drives, purging voter rolls, and limiting early voting have made the landscape more hostile. What CSS accomplished with minimal legal interference would face significant obstacles in many states today.

Measurable Outcomes: Registration vs. Turnout

Countdown 88 didn’t just register voters—it built infrastructure for sustained turnout through Countdown 89 and beyond. The campaign’s success can be measured in David Dinkins’s 1989 victory, the continued engagement of voters registered during the campaign, and the CSS leadership in the successful restructuring of New York City government that followed. This restructuring expanded the City Council from 35 to 51 seats and created new districts that gave communities of color—the same communities Countdown had registered—unprecedented representation in city government.

Modern campaigns often prioritize registration numbers as the key metric, but struggle with follow-through. Digital registration is easy; ensuring new registrants actually vote is harder. Countdown 88’s integration with GOTV operations through the Citizenship Education Fund and community networks created a pathway from registration to actual voting that many contemporary efforts lack.

What Modern Organizers Can Learn

The most important lesson from Countdown 88 voter registration NYC: sustainable political power requires institutional infrastructure, not just viral moments. Digital tools can scale reach, but they can’t replace the relationships, community accountability, and sustained presence that made Countdown 88 transformative.

Modern campaigns would benefit from Countdown’s institutional approach: securing foundation backing, building stable organizational infrastructure, training professional staff, maintaining year-round presence, and integrating registration with long-term political strategy rather than treating it as an isolated campaign tactic.

Legacy and Loss

Though Countdown 88 changed the political landscape, its records remain elusive. Today, Countdown is largely absent from CSS’s public archive. Press coverage survives, but the internal reports, proposals, and correspondence — while likely preserved — are not catalogued or publicly accessible.BlackPolitics.org is working to restore that archive — not to reframe CSS’s identity, but to honor the full scope of Countdown’s impact.

Bill Lynch NYC voter campaign innovations, including the integration of registration with long-term turnout operations and the use of nonpartisan structures to achieve partisan goals, influenced Democratic field operations for decades.

Jesse Jackson, now battling Parkinson’s disease, remains a towering figure in Black and American political history. As tributes mount, many will seek connection to his legacy — and rightly so. But Countdown 88 was never about the candidate. It was about building lasting infrastructure, empowering communities, and mobilizing voters across New York City. It showed what was possible when civic engagement was strategic, inclusive, and unapologetically rooted in both racial justice and economic equity. That’s the legacy worth preserving.

Lessons from Countdown 88: What Today’s Organizers Can Learn

The Countdown 88 voter registration NYC campaign offers timeless lessons for contemporary organizers seeking to build sustainable political power. While technology has evolved, the fundamental principles that made Countdown 88 successful remain relevant.

Lesson 1: Institutional Partnership Provides Credibility and Protection

Selwyn Carter Countdown 88 29success depended on Community Service Society backing. CSS’s established reputation, nonprofit status, and institutional resources provided:

- Legal protection for aggressive voter registration in hostile political environments

- Foundation funding that grassroots groups couldn’t access independently

- Media credibility that made Countdown 88 newsworthy rather than merely partisan

- Organizational infrastructure including office space, phones, and administrative support

Modern Application: Today’s organizers should seek partnerships with established civic institutions—universities, libraries, labor unions, religious denominations—that can provide similar benefits. Rather than operating as isolated grassroots efforts, embedding voter registration within trusted institutions increases reach and sustainability.

Lesson 2: Nonpartisan Structure Enables Partisan Outcomes

The genius of Community Service Society voter registration was maintaining nonpartisan credentials while pursuing clearly political goals. Countdown 88 didn’t explicitly campaign for candidates, yet the voters it registered overwhelmingly supported progressive candidates like David Dinkins first Black mayor NYC.

Modern Application: In today’s polarized environment, nonpartisan voter registration faces even greater scrutiny. However, the model remains powerful: register everyone eligible, focus on historically underrepresented communities, and let demographic realities shape political outcomes. Organizations like the Voter Participation Center successfully use this model today.

Lesson 3: Celebrity/High-Profile Endorsers Create Media Moments

Lesson 3: High-Profile Endorsers Create Media Moments

Countdown 88’s strategic use of high-profile figures generated media coverage that multiplied the campaign’s reach. The campaign’s masterstroke was the August 21, 1988 rally at Greater Bibleway Temple in Brooklyn that brought together Jonathan Jackson (son of Jesse Jackson), Dexter King (son of Martin Luther King Jr.), and Attallah Shabazz (daughter of Malcolm X)—the children of three iconic movements standing together to launch Countdown’s Get Out The Vote drive.

This wasn’t celebrity endorsement for glamour—it was calculated strategy to:

- Generate massive media attention (the symbolism was irresistible to press)

- Connect Countdown to civil rights legacy without partisan entanglement

- Create generational bridge between movement history and contemporary organizing

- Maintain nonpartisan credentials (they weren’t candidates or partisan figures)

Similarly, Rosa Parks’s appearances at churches in Harlem and Brooklyn provided moral authority and community excitement while preserving Countdown’s nonpartisan status.

Modern Application: Modern campaigns often overuse celebrity endorsements without strategic purpose. Countdown’s lesson: use high-profile figures to launch specific phases of campaigns, reach particular communities, or generate media attention at critical moments—but choose figures whose symbolism serves your mission without compromising your structure. Quality and strategic fit matter more than quantity or fame.

Lesson 4: Multiple Registration Venues Reach Different Communities

Countdown 88 voter registration NYC and NYC voter mobilization 1988 succeeded by meeting people where they were: subway stations during rush hour, churches on Sunday, colleges during registration week, community centers, welfare offices, and employment centers. The Votemobile 3,24went to high-traffic locations, while deputized registrars worked inside institutions.The campaign even positioned the NYC Votemobile 1988 outside the World Trade Center for an entire week—a high-visibility location that demonstrated Countdown’s nonpartisan commitment to registering all eligible voters while maintaining focus on underrepresented communities.

Modern Application: Digital registration tools are convenient but they miss people without internet access or comfort with online forms. Effective modern campaigns combine online registration with targeted in-person drives in locations that serve specific communities—barbershops, nail salons, DMV offices, community colleges, and naturalization ceremonies.

Lesson 5: Year-Round Organizing Beats Election-Year Mobilization

Countdown 88 began in December 1987—nearly two years before the 1989 mayoral election that benefited from its work. This long runway allowed for systematic voter registration, follow-up to ensure registration was complete, and relationship-building that paid dividends in turnout.

Modern Application: Too many campaigns treat voter registration as an election-year activity. Countdown’s lesson: build year-round infrastructure that can scale up during election cycles but maintains presence between elections. Organizations like Georgia’s New Georgia Project successfully use this model.

Lesson 6: Integration of Registration and GOTV Creates Complete Pipeline

Countdown 88 wasn’t an isolated registration drive—it fed directly into Countdown 89’s Get Out The Vote operation. The same organizations, volunteers, and infrastructure that registered voters in 1988 turned them out in 1989.

Modern Application: Modern campaigns often separate registration and GOTV operations, losing institutional knowledge and relationships. Effective organizing integrates both phases, using registration as the beginning of a relationship that continues through multiple election cycles.

Lesson 7: Data and Targeting Enable Efficient Resource Allocation

Selwyn Carter Countdown 88 director’s 29 team used precinct-level data to identify neighborhoods with low registration rates and high potential for progressive voters. This targeting allowed efficient allocation of limited resources—focusing the Votemobile, volunteer canvassers, and media buys where they would have maximum impact.

Modern Application: Data-driven targeting has exploded with big data and analytics, but the principle remains the same. Know your universe of potential registrants, prioritize high-value targets, and measure results to adjust tactics. Modern campaigns have better data but don’t always use it as strategically as Countdown 88 did.

Lesson 8: Training Creates Multiplier Effect

Countdown 88 invested heavily in training volunteer deputy registrars, teaching them not just how to register voters but how to engage community members, handle objections, and follow up. This training created hundreds of organizers who could work independently and train others.

Modern Application: Many modern campaigns prioritize quantity of volunteers over quality of training. Countdown’s lesson: intensive training that teaches both technical skills and political education creates organizers who can replicate themselves, creating exponential growth in capacity.

Lesson 9: Labor Union Partnership Provides Volunteer Army

AFSCME District Council 37, SEIU 1199, and other unions provided volunteers, resources, and institutional support that amplified Countdown 88’s capacity far beyond what CSS alone could provide. Labor’s organizing infrastructure and member mobilization capabilities proved essential.

Modern Application: Despite organized labor’s relative decline, union partnerships remain valuable for progressive voter registration. Unions can provide trained volunteers, funding, phone banks, and access to working-class communities that digital campaigns miss. Building labor-community coalitions should remain a priority.

Lesson 10: Success Requires Patience and Long-Term Vision

The infrastructure that elected David Dinkins first Black mayor NYC wasn’t built in months—it took years of patient organizing, relationship-building, and strategic planning. The Harlem Gang of Four’s decision to invest in voter registration years before the mayoral election showed strategic thinking that transcended immediate electoral concerns. Additionally, organizing in 1984 for the first Jesse Jackson campaign led by Al Vann and the Brooklyn based Coalition for Communirty Empowerment was foundational in the initial phase of registering unregistered black voters in New York.

Modern Application: In an era of viral moments and social media campaigns, Countdown 88 voter registration NYC reminds organizers that sustainable political power requires infrastructure that outlasts any single election. Investment in long-term capacity-building pays greater dividends than short-term mobilization.

Frequently Asked Questions About Countdown 88

What was Countdown 88 voter registration NYC?

Countdown 88 voter registration NYC was a citywide nonpartisan voter mobilization campaign that registered over 250,000 Black and Latino New Yorkers for the 1988 presidential election.

Who organized Countdown 88?

Countdown 88 was organized by Selwyn Carter29 and sponsored by the Community Service Society of New York under David R. Jones’s leadership, with strategic backing from Bill Lynch and the Harlem Gang of Four, and major labor unions in New York City..

How many people did Countdown 88 register?

Countdown 88 registered hundreds of thousands of new voters in NYC, with press reports crediting the campaign with mobilizing historic turnout in Black and Latino communities.

Did Countdown 88 help elect David Dinkins?

Yes, even though Countdown 88 and its successor Countdown 89 were non-partisan voter registration campaigns, they built the voter infrastructure and mobilization capacity that helped elect David Dinkins as NYC’s first Black mayor in 1989. The non-partisan structure allowed the Community Service Society to sponsor the effort while the newly registered voters formed part of the base for Dinkins’s campaign.

Charter Revision and Redistricting Impact

The momentum from Countdown 88 and 89 fed directly into structural reforms. In 1989, the New York City Charter Revision 28 expanded the City Council from 35 to 51 seats, creating new districts where communities of color could finally secure representation. The Community Service Society’s Redistricting Project, which I also directed29, played a central role in ensuring those gains were realized.

📚 References

Contemporary Press Coverage

- New York Times, “Voter Registration Drive Takes Aim at Minorities,” Dec 13, 1987.

- New York Times, “Civil Rights Patron Saint Comes to Brooklyn,” Jan 24, 1988.

- Newsday, “Sidewalk Sale on Democracy,” Dennis Duggan, Feb 21, 1988.

- Amsterdam News, “Major Voter Registration Project Launched,” Dec 18–19, 1987.

- USA Today, Feb 1, 1988.

- New York Observer, Jan 25, 1988.

- The City Sun, Jan 27, 1988; Aug 17, 1988.

- New York Daily News, Aug 22, 1988.

- New York Voice, Aug 27, 1988.

- Noticias Del Mundo, Mar 30, 1988.

Institutional & Organizational Sources

- Community Service Society of New York (CSS) archives and staff pages (David R. Jones).

- SEIU Local 1199 records of Dec 13, 1987 kickoff.

- AFSCME District Council 37 newsletters (Pat Caldwell).

- Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (Jim Bell).

- Council of Black Elected Democrats (COBED) meeting records.

- Citizenship Education Fund GOTV documentation (1988).

- Inner City Broadcasting (WBLS/WLIB) programming logs.

Biographical & Contextual References

- William “Bill” Lynch Jr.: obituaries and retrospectives on coalition strategy.

- David N. Dinkins: campaign histories referencing “gorgeous mosaic.”

- Basil Smikle Jr., “Percy Sutton, Eric Adams and the State of Black Political Power in New York,” Vital City, Oct 2025.

- Percy Sutton and Harlem Gang of Four biographies.

- Countdown 88 staff: Pat Caldwell, Anna Marta Morales, Lorraine Witherspoon-Flateau, John Flateau, Tracey Gray, Norma Bradshaw, Melvin Kelly, Joseph Haslip, John Anthony Butler.

Events & Artifacts

- Sydenham Hospital mobilization (Columbia University “Shoeleather” podcast; NYC press archives).

- Votemobile coverage (Newsday, Feb 21, 1988).

- Church rallies: Abyssinian Baptist, House of the Lord, Antioch Baptist.

- Celebrity PSAs: LL Cool J, RUN DMC.

- “Children of the Movement” rally program, Aug 21, 1988, Greater Bibleway Temple.

- NYC Charter Revision Commission documents (expansion of City Council seats).

Authorial Documentation

- Selwyn Carter — Director of Countdown 88, Countdown 89, and the Community Service Society Redistricting Project under David R. Jones; architect and editor‑in‑chief of Black Politics; former SRC staffer under Steve Suitts; participant in NYC civic mobilizations including Sydenham Hospital, African Americans United for David Dinkins, Coalition to Save Sydenham Hospital, Black United Front, and NYC Outward Bound.

- Author of Countdown 88: When NYC’s Majority Mobilized (Black Politics, 2025), integrating lived experience with archival research.

- Professional profile: Selwyn Carter on LinkedIn.

Explore More:

- Jesse Jackson: Architect of Black Political and Economic Power

- Southern Regional Council and Black Political Power

- Harlem Gang of Four Political Strategy: City Hall to DC

- Coalition for Community Empowerment: Brooklyn Answers Harlem

- Stacey Abrams and Power of Black Vote in South

October 20th, 2025