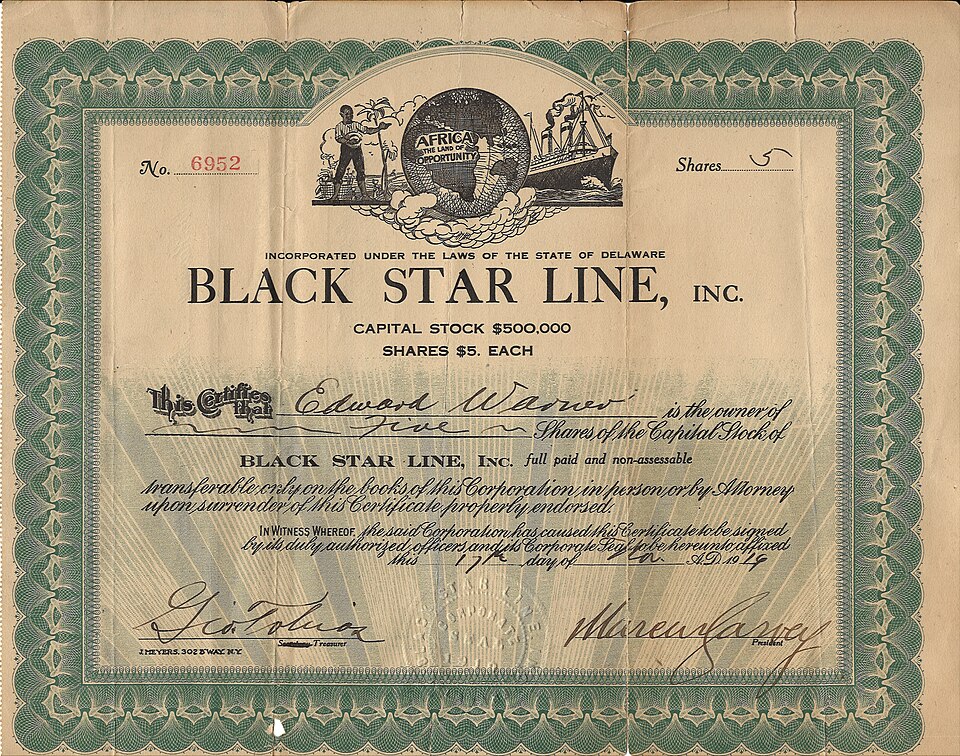

Black Star Line Stock Certificate

Movement Economics in the Black Political Struggle

Black movement economics has historically been interwoven with efforts to build black political power. Economic self-determination has always been central to long lasting efforts to build Black political power. Across generations, movements have built institutions, launched cooperatives, and challenged capitalist structures that excluded Black communities. Here’s a deep dive into four pivotal models:

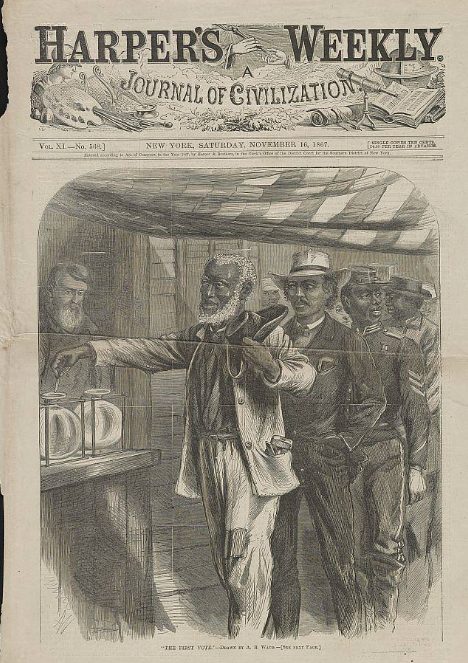

1️⃣ Garvey Movement: Global Black Capitalism

Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was one of the earliest and most ambitious efforts to build Black economic infrastructure. In the 1920s, Garvey launched the Black Star Line, a shipping company meant to connect diasporic communities and promote global trade. He also founded factories, newspapers, and a savings bank—urging Black people to “buy Black,” invest in Africa, and reject white economic dependency.

Garvey’s model was pan-African, entrepreneurial, and unapologetically capitalist. Though the Black Star Line ultimately collapsed, the movement seeded a lasting ethos of Black ownership and transnational solidarity.

🚢 Why Did the Black Star Line Collapse?

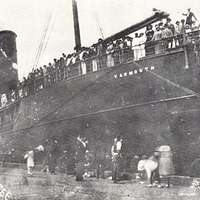

Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line, launched in 1919, was a bold attempt to build Black global commerce—connecting African Americans with Africa and the Caribbean through shipping and trade. But despite its visionary scope, the venture collapsed by 1922 due to a mix of internal and external pressures:

- Underfunding and mismanagement: The ships purchased were often in poor condition, and maintenance costs ballooned.

- Sabotage and infiltration: U.S. government agents, including J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau of Investigation, infiltrated the UNIA and undermined operations.

- Fraud charges: Garvey was convicted of mail fraud in 1923 for promoting stock in the Black Star Line, despite widespread belief that the charges were politically motivated.

- Logistical challenges: The company struggled with scheduling, cargo handling, and international coordination—especially without access to mainstream shipping infrastructure.

Despite its collapse, the Black Star Line remains a symbol of diasporic ambition and economic self-determination. It inspired future movements to think globally and build independently.

2️⃣ Nation of Islam: Economic Discipline and Independence

The NOI under the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and later Minister Louis Farrakhan emphasized economic discipline as a spiritual and political imperative. Members were encouraged to avoid debt, support Black owned businesses, and build self-sufficient institutions. The NOI operated farms, bakeries, clothing stores, and schools—creating a parallel economy rooted in faith and racial pride.

This model fused religious identity with economic strategy, offering dignity through ownership and control. It also challenged exploitative systems by creating alternatives—however limited in scale.

☪️ Nation of Islam Economic Infrastructure (Expanded)

The Nation of Islam (NOI) built one of the most recognizable and community-rooted economic ecosystems in Black America—especially under the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and later Minister Louis Farrakhan. Their model emphasized self-sufficiency, discipline, and dignity, with tangible enterprises that became cultural staples:

- Whiting Fish Sales: NOI members sold frozen whiting fish door-to-door, often in underserved neighborhoods. This wasn’t just commerce—it was outreach, employment, and nutrition rolled into one.

- Bean Pies: A signature NOI product, bean pies were sold by members in cities across the country. They became a symbol of Black entrepreneurship and cultural pride.

- Restaurants: NOI-operated eateries like Steak & Take (often misremembered as “Steak and Shake”) served affordable meals and employed community members.

- Farms and Food Distribution: The NOI owned farmland in Georgia and elsewhere, producing crops and distributing food through its own networks.

- The Final Call Newspaper: Sold by members on street corners, this publication was both a revenue stream and a tool for ideological education.

- Schools and Clothing Stores: NOI institutions provided uniforms, education, and moral instruction—creating a parallel infrastructure outside mainstream systems.

These enterprises weren’t just economic—they were cultural, spiritual, and political. They gave Black communities a sense of ownership, pride, and purpose.

3️⃣ Black Christian Churches: Mutual Aid and Civic Infrastructure

Black churches have long served as economic anchors in their communities. Through mutual aid societies, scholarship funds, and housing programs, churches redistributed resources and supported families in need. Denominations like the AME and COGIC invested in schools, hospitals, and credit unions—often filling gaps left by public institutions.

During the civil rights era, churches funded voter drives, bailed out protesters, and hosted economic justice campaigns. Their model was communal, faith-driven, and deeply rooted in service.

✝️ Black Church Economics: Recognizable Examples

Black churches have long been economic anchors in their communities—funding education, housing, and civic engagement. Here are some specific, resonant examples:

- Credit Unions: AME and Baptist churches helped launch community credit unions, offering loans and financial literacy to members excluded from traditional banks.

- Scholarship Funds: Churches like Ebenezer Baptist in Atlanta and West Angeles COGIC in Los Angeles have awarded thousands in scholarships to Black youth.

- Housing Initiatives: Some churches developed affordable housing complexes—like Allen AME in Queens, which built senior housing and community centers.

- Church-Owned Businesses: From bookstores to daycare centers, churches created employment and services tailored to Black families.

- Economic Justice Campaigns: During the civil rights era, churches boycotted segregated businesses and promoted “Buy Black” campaigns—often hosting Black vendor expos and cooperative markets.

These efforts weren’t just charitable—they were strategic. Churches used their moral authority and financial resources to build infrastructure and challenge inequality.

🧠 What Was Operation Breadbasket?

Operation Breadbasket was a strategic economic initiative launched by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1962 and led by Jesse Jackson in Chicago starting in 1966. Its goal: leverage Black consumer power to demand fair employment and business practices.

Key tactics included:

- Economic Boycotts: Targeting companies that profited from Black consumers but refused to hire Black workers.

- Negotiated Agreements: Jackson and others brokered deals with corporations to increase Black hiring, promotion, and supplier contracts.

- Community Monitoring: Breadbasket teams tracked compliance and held businesses accountable.

- Public Campaigns: They used media and church networks to mobilize support and pressure targets.

Operation Breadbasket laid the groundwork for Jackson’s later work with Operation PUSH and the Rainbow Coalition. It showed that economic strategy could be a form of civil rights activism—and that the Black dollar had power.

4️⃣ Black Panther Party: Survival Programs and Socialist Praxis

The Panthers approached economics through a revolutionary lens. Their Survival Programs—free breakfast for children, health clinics, clothing drives—were designed to meet immediate needs while exposing systemic neglect. They also advocated for land reform, universal healthcare, and guaranteed income—drawing from socialist and Marxist traditions.

Though often remembered for armed resistance, the Panthers’ economic work was foundational. It built trust, mobilized communities, and modeled what a just economy could look like.

✊🏾 Black Panther Party Operations: Economic Praxis

The Black Panther Party (BPP) approached economics as a tool of survival and resistance. Their Survival Programs were designed to meet immediate needs while exposing systemic neglect. Key examples include:

- Free Breakfast for Children: Served thousands daily in cities like Oakland, Chicago, and New York. This program inspired federal school breakfast initiatives.

- Community Clinics: Panthers operated free health clinics offering screenings, treatment, and education—especially around sickle cell anemia.

- Clothing Drives and Food Distribution: They organized giveaways and mutual aid programs, often partnering with local grocers and donors.

- Transportation and Elder Care: Panthers provided rides to seniors and supported families navigating healthcare and legal systems.

- Educational Programs: Liberation schools taught Black history, political theory, and literacy—empowering youth beyond the public school curriculum.

These programs were rooted in socialist praxis but tailored to Black community realities. They built trust, modeled justice, and challenged the state to do better.

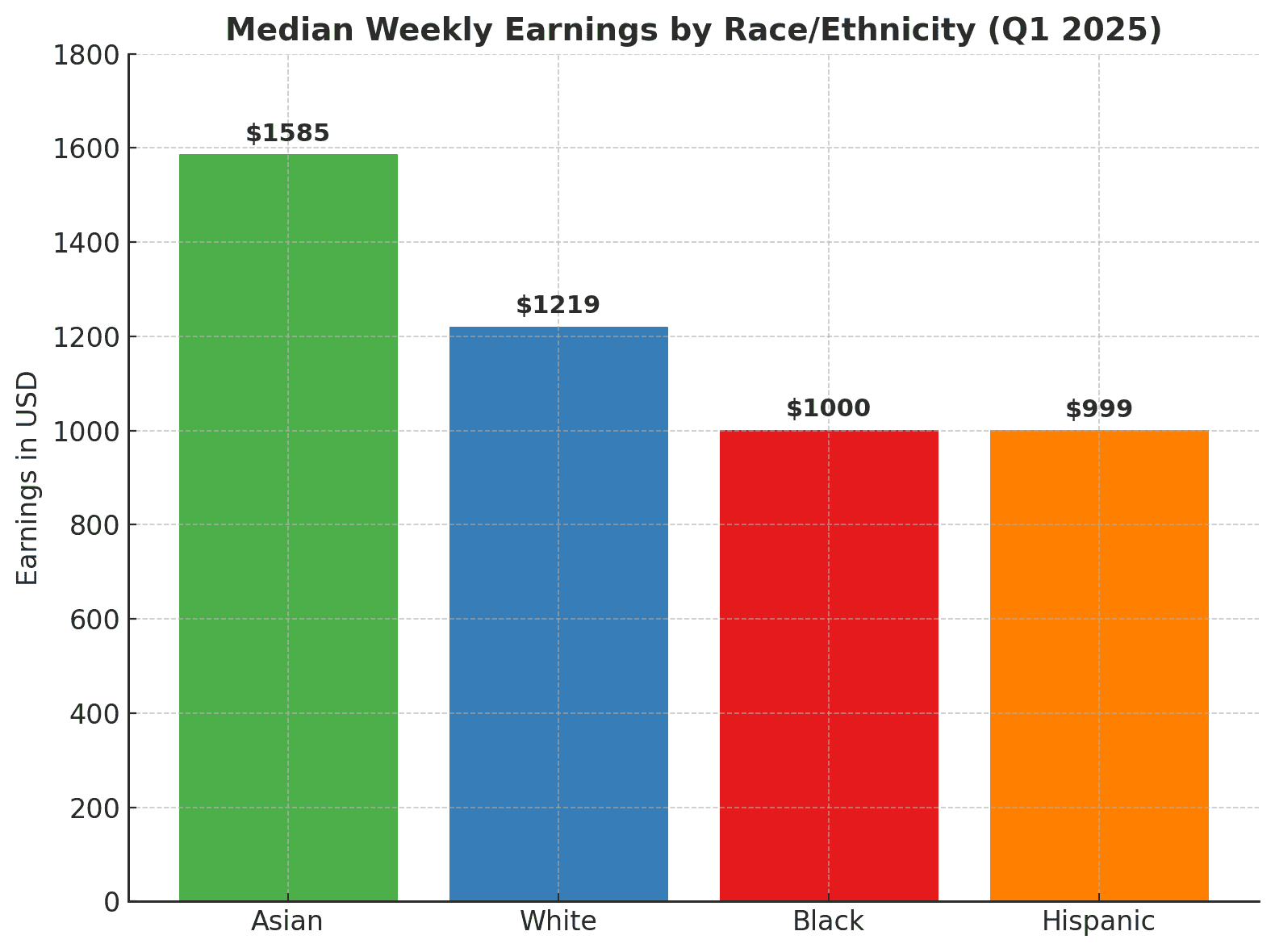

🔍 Black Movement Economics Comparative Table

| Movement | Economic Model | Institutions Built | Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garvey | Pan-African Capitalism | Black Star Line, UNIA factories | Diasporic entrepreneurship |

| NOI | Religious Self-Sufficiency | Farms, schools, businesses | Cultural pride, discipline |

| Churches | Communal Mutual Aid | Credit unions, hospitals, scholarships | Civic infrastructure |

| Panthers | Revolutionary Socialism | Survival Programs, clinics | Grassroots empowerment |

Movement Economics & Institutional Models

- PBS: Marcus Garvey & UNIA

- Wikipedia: Black Star Line

- BPP Alumni Network

- PBS: Panther Survival Programs

October 4th, 2025