✝️ The Black Christian Church: Backbone of the Movement

The Black Christian Church has been the spiritual, strategic, and social backbone of the Black freedom struggle for over two centuries. From the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1816 to the civic engagement of today’s Baptist and Pentecostal networks, the church has nurtured leaders, housed movements, and mobilized communities.

Black Christian Church: Background & Context

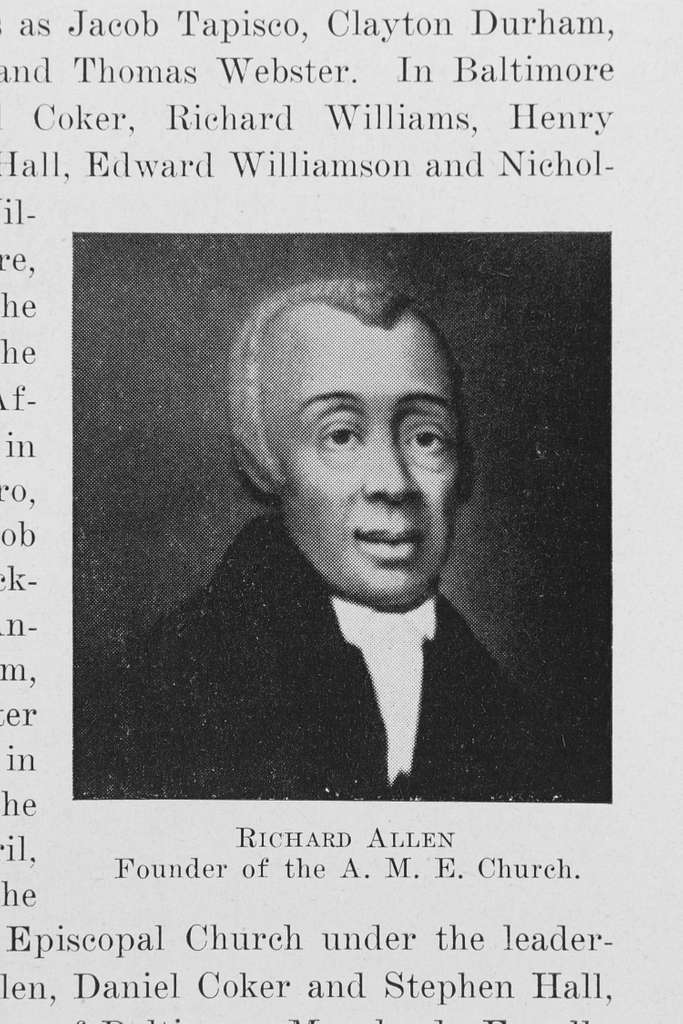

Richard Allen, a formerly enslaved preacher, founded the AME Church to create a space where Black worshippers could gather free from white control. His vision was radical: a denomination rooted in liberation, education, and self-determination. The AME Church quickly became a hub for abolitionist organizing, literacy campaigns, and political advocacy.

Faith and Freedom in the 19th Century

The roots of the Black Church lie in the quest for both spiritual salvation and human liberation. During slavery, Black worshippers created independent spaces of prayer that blended African rhythms, biblical hope, and coded messages of resistance. Enslaved preachers used Scripture as a tool of survival, often invoking the Exodus story — “Let my people go” — as both divine command and political declaration.

When Richard Allen founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, he established more than a denomination: he created a model for Black self-determination. That church’s congregations and their sister bodies — like the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church and the Colored Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church — built schools, published newspapers, and organized early abolitionist campaigns. The pulpit

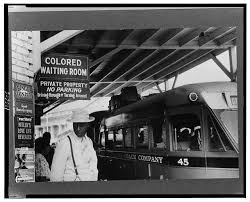

Throughout Reconstruction and Jim Crow, Black churches served as sanctuaries of resistance. They hosted voter registration drives, taught civic literacy, and provided mutual aid. The National Baptist Convention, founded in 1880, became one of the largest Black organizations in the country—linking congregations across the South and Midwest in a shared mission of uplift and advocacy.

SCLC – Impact of Black Christian Church

In the 1950s and 60s, the church’s role became even more pronounced. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a Baptist minister, helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which coordinated nonviolent protests, boycotts, and voter drives. Churches became command centers for civil disobedience, training grounds for activists, and moral anchors for the movement.

The Selma marches, Montgomery Bus Boycott, and countless other campaigns were powered by church networks. Clergy like Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, and C.T. Vivian used their pulpits to preach justice and organize action. The Church of God in Christ (COGIC), with its massive national reach, also played a key role—especially in mobilizing rural and urban congregations.Younger church leaders like Reverend Orange and Jesse Jackson played pivotal roles in the movement. Reverend Orange was a key figure in the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the Selma to Montgomery march. Jesse Jackson was the leader of Operation Breadbasket.

Even as the movement evolved, the church remained central. In the 1980s and 90s, Black churches hosted candidate forums, built voter education programs, and partnered with labor and civil rights groups. They became bridges between generations, linking elders who marched with youth who organized.

Today, Black churches continue to shape political discourse. AME, Baptist, and COGIC congregations lead voter mobilization efforts, advocate for criminal justice reform, and provide platforms for civic engagement. They host Souls to the Polls events, partner with advocacy organizations, and serve as trusted messengers in communities often ignored by mainstream politics.

The Black Church is not just a religious institution—it’s a political force. Its legacy is one of faith in action, rooted in scripture and struggle. It reminds us that the fight for justice is sacred, and that the pulpit can be a platform for liberation.

Rev. William Barber – Moral Mondays – The Poor People’s Campaign

Today, Reverend Dr. William Barber II stands in a long tradition of Black church leaders who have used their pulpits as a base for social and political activism. Drawing on the Black church’s history of organizing for justice, Barber has led movements like the Moral Mondays in North Carolina and co-chairs the Poor People’s Campaign, which link moral theology with calls for economic and racial justice.

Black Christian Church & Civic Power

- National SCLC Legacy

- Pew Research: Black Religious History

- Pluralism Project: African American Christianity

October 6th, 2025